Since the attacks of 11 September 2001, there have been over 45,100 deadly terrorist acts committed in the name of Islam. Many today who seek to excuse Islam for the acts of violence committed by jihadists point out that such Muslims are misinterpreting the Quran, their holy book. Such apologists, even Pope Francis, sustain that the Quran ‘is a book of peace’. Yet the immediate perception after reading the Islamic texts, as well as their juridical interpretation as dictated by the sharia—Islamic law—suggests otherwise.

As the late Dr. Nabeel Qureshi, a convert from Islam to Christianity, had explained, when growing up as a Muslim in Pakistan, he and many others falsely believed Islam to be a peaceful religion:

‘It wasn’t until I started reading the sources for myself – the Quran and the hadiths – that I saw the sources showed that Islam at its historical core was violent.’

In truth, Islamic terrorists, says Qureshi, ‘are inspired by the literal interpretation of Muslim sacred texts’, such as:

- ‘So if you, [O Muhammad], gain dominance over them in war, disperse by [means of] them those behind them that perhaps they will be reminded.’ — Sura 8, 57

- ‘And when the sacred months have passed, then kill the polytheists wherever you find them and capture them and besiege them and sit in wait for them at every place of ambush. But if they should repent, establish prayer, and give zakah, let them [go] on their way. Indeed, Allah is Forgiving and Merciful.’ — Sura 9, 5

- ‘The Jews say: ‘Ezra is the son of Allah’; and the Christians say: ‘The Messiah is the son of Allah.’ That is their statement from their mouths; they imitate the saying of those who disbelieved [before them]. May Allah destroy them; how are they deluded?’ — Sura 9, 30

- Allah’s Apostle said: ‘The Hour will not be established until you fight with the Jews, and the stone behind which a Jew will be hiding will say. ‘O Muslim! There is a Jew hiding behind me, so kill him.’’ — Sahih al-Bukhari Book 52, 177

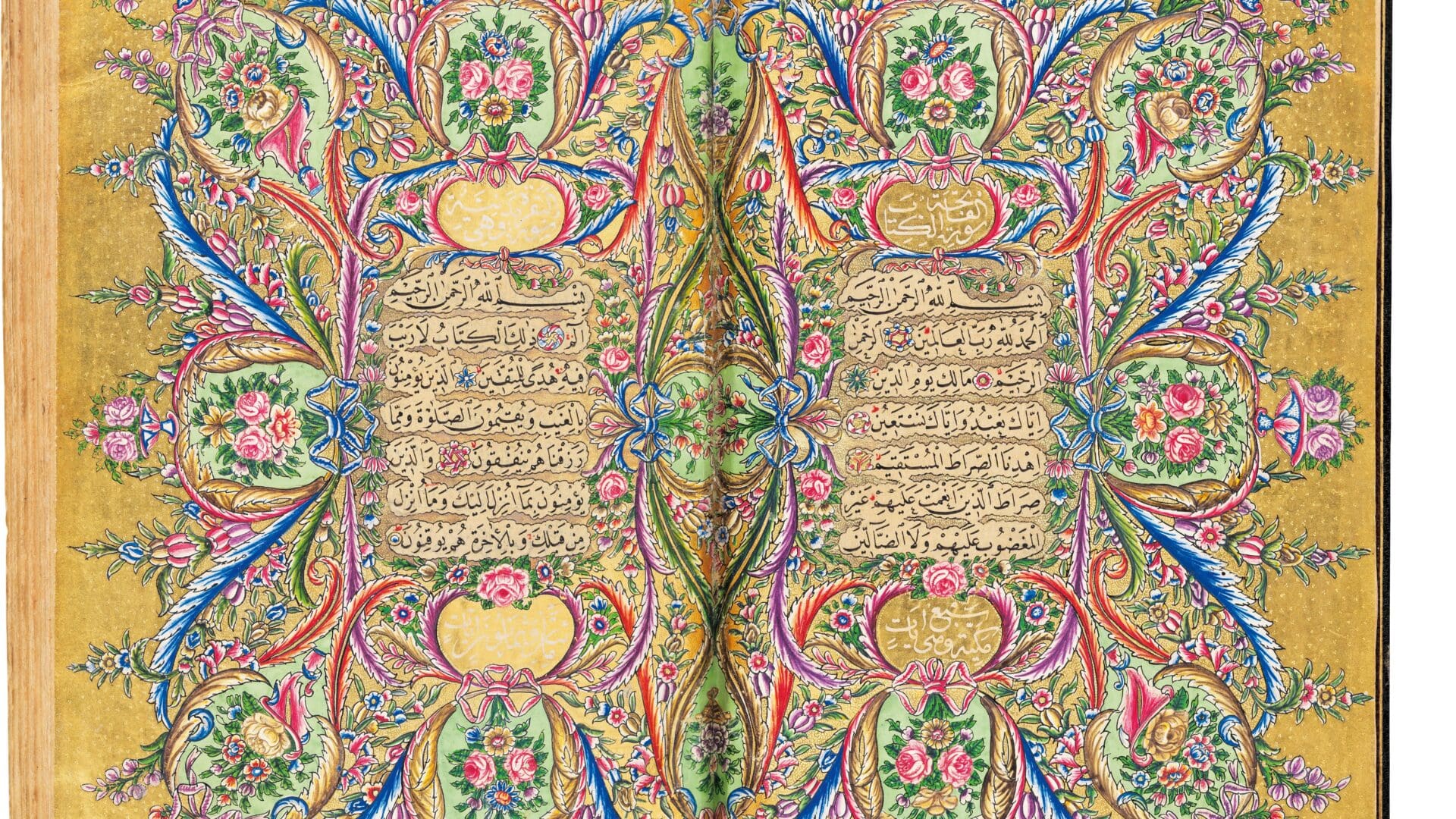

The Essence of the Quran

The Quran, which literally means ‘the recitation,’ is the sacred text and the primary fountain of law for all Muslims. They believe that it contains the literal word of God, which was gradually revealed by Allah to the Prophet Muhammad over a twenty-three-year period (609–632). Muslims also believe that Allah promised to guard the holy book from any possible alterations, revisions, deletions, or redactions. Therefore, while they may disagree about the meaning and importance of the revelation, there is a broad consensus on the integrity and infallibility of the text. Islamic jurists commonly agree that the Quran covers all aspects of human life, either expressly or by implication, which binds them to use it to settle any dispute.

In the Bible, the human writer of the sacred text writes under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, which in essence makes him a co-author with God. This is evident by some of the titles in both Testaments: the Book of Job, the Gospel according to Mark, the Epistle of James, and so on. In Islam, the Quran is not co-authored by anyone. It is a literal transcript of Allah’s words, which have always been present with Allah and descended unto Muhammad.

Every single word, every single letter in the Quran, remains exactly as it was made known from Allah to Muhammad down to our present day. The Quran is Allah’s unchangeable and eternal expression; its immutability is the essential foundation for the sharia, a law for all time.[1] Therefore, because Muslims hold that the Quran was sent down by Allah, there is not the slightest possibility for any critical or historical interpretation, not even for those elements that are indisputably related to the traditions of a specific historical period and culture.

It is difficult to take the Quran as a historical book, in part because the Muhammad’s attributed sayings were collected by several of his companions—scribes who were responsible for recording the revelations shortly after his death. Since these codices were first memorized before they were penned down, there were naturally not free of discrepancies. As a result, around, 653, Caliph Uthman destroyed the Quranic copies extant during his time and commissioned a standard and universal version (also known as Uthman’s Codex), which is generally considered the archetype of the Quranknown today:[2]

So Uthman sent a message to Hafsa saying, ‘Send us the manuscripts of the Quran so that we may compile the Quranic materials in perfect copies and return the manuscripts to you.’ Hafsa sent it to Uthman. Uthman then ordered Zaid Ibn Thabit, Abdullah bin Azubair, Said bin Al-As and Abdur Rahman bin Harith bin Hisham to rewrite the manuscripts in perfect copies.… Uthman sent to every Muslim province one copy of what they had copied, and ordered that all the other Quranic materials, whether written in fragmentary manuscripts or whole copies, be burnt. — Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 61, hadith 510

The task of trying to determine the context of the 114 suras in the Islamic sacred book is challenging, since the narrative passages are minimal. Part of this difficulty extends from the unresolved questions as to how it reached its classical form. The Quran largely tends to come off as a collected series of acclamations by Allah, without statements particularizing the time or circumstance the declarations refer to. Jurists compensate this vacuum by pointing to the posthumous hadiths, which they claim complement the context of equivocal verses.[3]

One can then argue that the so-called Muslim fundamentalists wrongly justify their acts of violence. All this being said, there is confusion as to who speaks for Islam and how Islamic law (the sharia) is to be employed, especially in light of the Sunni-Shi’ite division. Nevertheless, the manner in which both physical and cultural jihadists invoke their legal tenets in order to justify their jihad leads one to confirm that their indiscriminate acts are sanctioned by the Islamic texts:

‘[Remember] when you asked help of your Lord, and He answered you: ‘Indeed, I will reinforce you with a thousand from the angels, following one another … I will cast terror into the hearts of those who disbelieved, so strike [them] upon the necks and strike from them every fingertip. That is because they opposed Allah and His Messenger. And whoever opposes Allah and His Messenger — indeed, Allah is severe in penalty.’ — Sura 8, 9; 12–13

[1] Nabeel Qureshi, No God but One: Allah or Jesus?. Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 2016, 272.

[2] Fred M. Donner, “The historical context,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Qur’ān, Jane D. McAliffe, ed., 4th ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006, 31–33. According to Shi’ite tradition, its first caliph, Muhammad Ali, compiled a version of the Quran shortly after Muhammad’s death. It differed from Uthman’s Codex in that his version was presented in chronological order. Nevertheless, he never opposed the standardized redaction of Uthman. See, Sayyid M. H Tabatabai, The Qur’an in Islam: Its Impact and Influence on the life of Muslims. London, Routledge, 1987, 98.

[3] Peter Townsend, Questioning Islam: Tough Questions & Honest Answers about the Muslim Religion. CenterSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014, 9–10.