On Sunday, many Hungarians attended Easter services in their local church. No small number of them won’t be seen there again until Christmas.

This is normal throughout the West. In my childhood, this is how my American family, in the conservative rural South, treated churchgoing: as something only really necessary on the two biggest holidays of the Christian year. It never occurred to my parents that Christians ought to be more faithful churchgoers. America is a Christian country, they thought, whether or not people like us went to church.

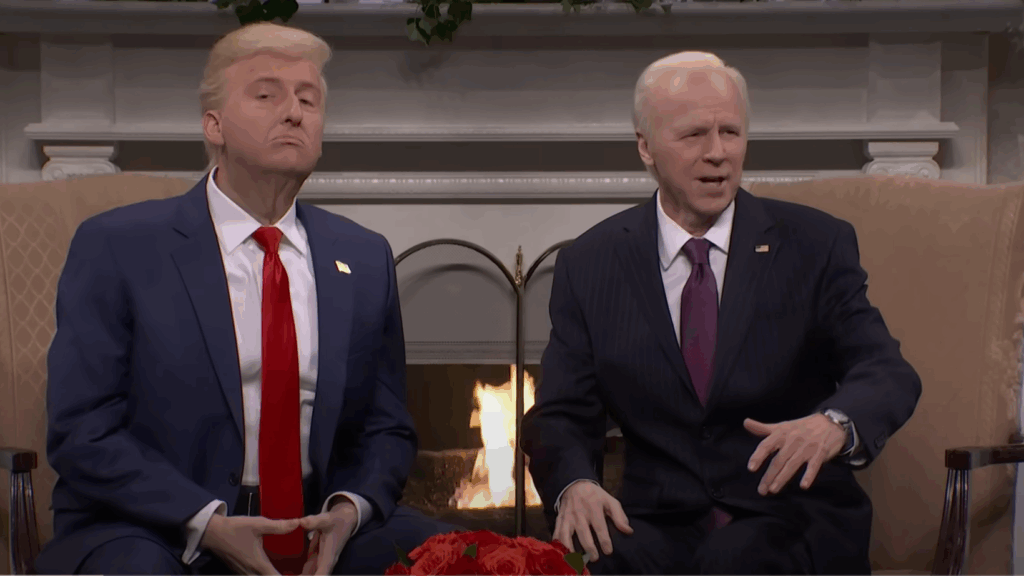

That was fifty years ago. Today, the number of Christians in the US is in steep decline, though the statistics are far better than in Europe. Conservative Christians were furious when President Joe Biden officially recognized Easter Sunday as ‘Transgender Day Of Visibility,’ and they were right to be. But Biden could only dare to make such a disrespectful move in a country that is far less Christian than it once was.

Meanwhile, in Great Britain, some Christians and others complained bitterly that in London, the city erected lights and banners to celebrate Ramadan, but had no similar display to mark Easter, the holiest day of the Christian calendar. The English writer Ben Sixsmith shares this sentiment, but he also said that you can’t expect a country to remain Christian if there are no Christians in it.

There are more Muslims in mosque on a given Friday than there are Anglicans in church on Sunday, he observed. It is true that British elites disdain Christian holidays, but the death of Christian Britain is happening because people like him (he confessed) want the UK to remain Christian, but don’t go to church, and don’t endeavor to live as faithful, engaged Christians.

After a period of teenage agnosticism, I found Christian faith in my twenties through the Catholic Church. When I told my Protestant father I was converting, he was shocked and hurt. It wasn’t because he was anti-Catholic. It was because, as he put it, ‘the Drehers have always been Methodist’—meaning that he considered my conversion to be a betrayal of family tradition. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that there was nothing in my childhood that conveyed to me the value of being Methodist, as our family rarely darkened the door of our town’s Methodist church.

For him, as for so many Americans, Christianity was simply part of the social landscape. The 19th century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had people like my family in mind when he wrote that when someone is considered to be a Christian only because he was born into a Christian society, then Christianity ceases to exist. This was a radical claim at the time, but time has revealed that Kierkegaard was right.

Kierkegaard’s point was that

Christianity, at its core, is neither a philosophy nor a social club, but a way of life.

If people don’t live it, it dies. To be fair, America has likely never been a country in which the majority of its people are in church on Sunday. Nevertheless, enough Americans did attend church to create a Christian culture. The culture that formed my late father was unabashedly Christian, so much so that an alternative was inconceivable.

Those days are gone. Generation Z, the name given to people born from the late 1990s through the early 2010s, are the least religious generation in American history. It’s not that they are all becoming atheists, but rather that they cease to identify with any particular church or religious tradition. They call themselves ‘spiritual, but not religious’. On current trends, the United States will cease to be a majority Christian nation by 2070.

This is all very old news to Europe, which has been de-Christianizing for far longer. Hungary is no exception. Many American conservatives, impressed by the Orbán government’s admirable fidelity to Hungary’s Christian roots, think of this country as a bastion of faith. Sadly, they are wrong. Hungary is one of the least religious countries in Europe, with fewer than one in five Hungarians attending services regularly, and even fewer agreeing with the statement that ‘my religion defines me as a person’.

Yet there remains in Hungary a relatively strong cultural Christianity. For example, the government’s desire to protect Hungarian children from transgressive sexuality is based in Christian norms, and it doesn’t try to hide it. Visitors to Hungary from western Europe or the United States are often surprised, even shocked, by the fact that there are no rainbow flags everywhere in Budapest, celebrating all things LGBT (the American Embassy during June, the high holy month of Pride, is an exception).

Hungary’s strong anti-migration policies are in part based on a desire to maintain the Christian character of the country. All it takes is a brief glance westward to European countries that have permitted mass migration from the Islamic world to see what fate awaits Hungary should it ever abandon its firm stance.

But these laws, policies, and practices will not long remain if the Hungarian people are unfaithful to their baptism.

Eduard Habsburg, Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See, said in a podcast last year, ‘If we don’t want to get swept away by the tide of this time, it only will be possible through Christianity. A country won’t remain conservative if it’s just based on conservative ideas. You need a bedrock of faith under that, or it will be blown away.’

He’s right. I lived through this process in America. Polls show that Generation Z is not only the least religious in American history, but its members are also strongly liberal in their political and social beliefs. There is a connection.

This transformation did not happen overnight. It began when too many well-meaning, nominal Christian parents assumed wrongly that Christianity would always be there. They didn’t actively practice their faith, and their children learned this lesson well. Social scientists who study religion say there is no factor more important in passing on the faith to one’s children than whether or not parents—especially fathers—are active churchgoers.

As Ambassador Habsburg said, cultural Christianity is not enough. Nor is voting for pro-Christian conservatives. Without a return to the faith, the sad, sorry state of Britain at Eastertide today is going to be Hungary’s fate tomorrow. You can’t have the benefits of Christianity without making the sacrifices necessary—on Sunday and every day—to make the faith live in the hearts of the Hungarian people.

If you went to church on Easter Sunday, great. Now return this coming Sunday. If you didn’t attend church on Easter, well, there’s nothing stopping you from showing up this Sunday. Go to church. You will not only save your soul, you might even save your nation.