The following is a translation of an interview written by Krisztina Salamin, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

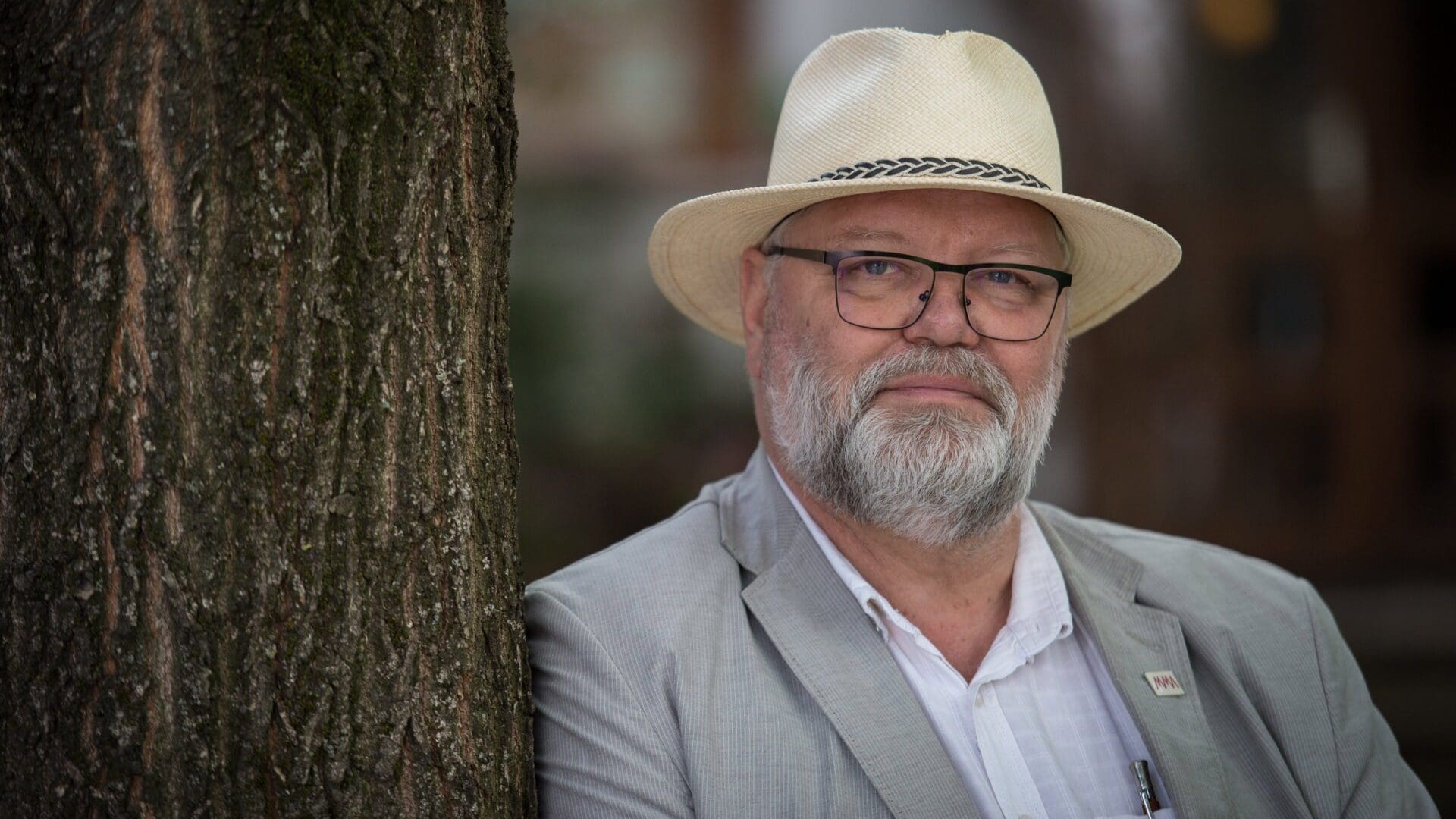

How does our childhood environment affect our present-day homes? What should be taught to the professionals of the future, and why should buildings not go out of style? Magyar Krónika asked Kossuth Prize winner Hungarian architect Attila Turi about appropriate Hungarian architecture, who also talked about how giving hope, in addition to the new houses, could help those in trouble in the area affected by the 2010 Hungarian red sludge disaster. You can read the interview below.

Attila Turi was a student of Kossuth Prize and Ybl Prize winner Hungarian architect Imre Makovecz, founder and ‘eternal and executive president’ of the Hungarian Academy of Arts. He is Vice President of the Chamber of Hungarian Architects and the Hungarian Academy of Arts, the former head architect of the town of Budakalász and currently of Pilisszentlászló. He took a leading role in the reconstruction after the Tisza flood in 2001 and following the red sludge disaster in 2010.

***

Did your childhood home influence your perception of architecture?

I believe that no matter where we grow up, whether on the eighth floor of a housing estate or in a family house, the image of ‘home’ is imprinted in our soul for the rest of our life. I feel extremely lucky because I grew up in Óbuda, in the Gas Factory Housing Estate designed by Hungarian architecture professor Loránd Almási Balogh, and I believe to this day that it is the centre of the world. In the 1960s, the area had a rural atmosphere: horse-drawn carts carrying manure still travelled on Szentendrei Road, while gypsy marketers on their way home stopped by the corner pub to have a drink. In addition, every apartment in the estate built for workers had a small garden attached to it. This omega-shaped building complex, surrounded by houses, with a kindergarten in the middle, had a special atmosphere. This place defined the direction I headed in and the scale of how I perceived the world.

In what sense?

From there, I have brought a kind of sensitivity to the environment, the proportions, the message of the buildings, and the quality of the details. Back then, lamplighters still walked the streets in the evenings—every night, an old man would tap the streetlamps with a long stick, which turned them on. I found it terribly funny that someone could make light with a stick. That world long gone got embedded in my subconscious. For example, we had heart-shaped holes cut in the middle of the green slats of our windows—all that in the sixties, when modern, simple lines wanted to suppress everything else. As an architecture student, obviously, I started drawing such shapes because they were what really affected me. Maybe those were the times I first thought about how to speak to other people, too. From this point of view, I see a serious problem in modern architectural discourse.

What is the problem today?

Three concepts were formulated in Greek philosophy, which were not questioned by anyone for more than two millennia.

Beauty, truth, and goodness.

However, these concepts given by God were replaced first by the Enlightenment and then by the modern conceptual system. Today, we say interesting, fashionable, and trendy instead of beauty; honesty instead of truth; and interest instead of goodness. We work and live in these relationships.

It can be felt in your works and thoughts that you were a student of Imre Makovecz, the creator of Hungarian organic architecture.

Correction, I still am a student of Imre Makovecz. This never passes. I do not agree with the view that one surpasses or outperforms one’s master. I only understood a slice of Imre Makovecz’s style- and thought-creating oeuvre. To my mind, I have to deepen and widen this delimited part. The basic premise that I have always kept in mind in my work also comes from my master, namely that the true value of a work of art is not self-realisation, but the accurate transmission of a certain culture. The essential concept of architecture, and I think of all art for that matter, is creative humility. As architects, we are in an ambivalent situation: bound on one side and free on the other, which is best expressed by Corbusier’s Modulor: one hand reaches down towards the earth and grasps at its substance, the other is raised above the clouds—and these two are united in us.

Do today’s masters also teach this concept to the architects of the future?

Architecture education, in addition to some great things, has several fundamental problems as well. One of the biggest issues is the lack of orientation, and the other is a lack of study groups. The latter can be partly attributed to the Bologna Process. As university students, my classmates and I regularly settled in the corridor behind the drawing department, watching each other, to see who would come up with a better solution to a particular task. It was a real workshop. Today, everything has become atomised; students have social anxiety and are pressured to be achievers. Their primary goal is to gain as many credits as possible and get good grades for further education, which makes them conformists already in their twenties. They do not turn inward, as Rainer Maria Rilke advises, but outward, which leads to disintegration. Besides, there is also a third problem, the cause of which is to be found in education itself. Namely, architecture is not based on architecture, but on general education. Today, however, there is nothing to build on, so the profession has begun to build on itself. And this is the basic problem. This is not about young people, but about how we deal with the challenges.

How can young people then be encouraged to form their communities again?

This is why we have organised university construction camps. In one of the camps, a girl did nothing but cut twenty-centimetre-long pieces of steel for a week. I tried to involve her in other kinds of work as well, but she only liked this because she was supplying the building block for the others and thus felt useful.

It would be beneficial to start university education in such a way that, in the first year, instead of teaching architecture, the foundations of a generic culturedness should be laid

and construction camps should be organised so that the students get to know each other and experience who is only ‘shade-tolerant’ and who is ready for real action. In addition, they should listen to philosophical lectures in the evenings so that their way of thinking also changes in this direction.

After Hungary’s most serious industrial accident, the red sludge disaster in Ajka in 2010, you played a major role in developing the town’s reconstruction plan. How does one start such a job?

The 2010 industrial disaster was caused by a private company. In a case like that, the state’s task is to save lives and remediate damages everywhere. In addition to these—and this is shown by many examples in the world, including the case of hurricanes and tsunamis—, most countries consider post-disaster recovery a private matter covered by donations or insurance. However, the Hungarian Government advanced the cost of the reconstruction and has been suing the company ever since. The Directorate General for Disaster Management contacted the architects of the Károly Kós Association on the fourth day after the disaster, and on the fifth day, we already started the reconstruction work. The first task was to find a place for the residents’ future homes. In Devecser, for instance, we chose a relatively higher location for the houses, as far away from the disaster as possible—not for scientific, but rather for psychological reasons.

How was it possible to talk about the future with those involved so soon after the tragedy?

Let us just imagine being one of the lucky victims who was not at home but at his workplace at noon at the time of the disaster. Thus, he did not suffer any burns, but was left with nothing but what was on him at the time. Not even a photo, a little pair of scissors, or a CD left. Nothing, just some pieces of clothing. We found people there in this state of mind. We considered the most important principle to treat them as if they wanted to build new homes of their own accord. The architects of the association developed fifteen sample plans, which could be adapted to the needs of the families affected. We held consulting hours continuously, where we looked at the selected plans with the families and then discussed what changes would be needed. During the consultations, we got to know these people and their needs, and we did not leave them alone during the construction either. We supervised the work throughout so that possible errors were not discovered when it was already too late. We even arranged for the future owners to see if everything is going well during the works. The construction took place with a huge joint effort; we started it in February and by the beginning of August, people could move into their new homes. Moreover, the architecture students of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics helped to build a playground during their summer camp, and a year later, after the death of Imre Makovecz, also a chapel on the site.

How could the image of the new houses be adjusted to that of the cities of Devecser and Kolontár?

The disaster management deemed the Károly Kós Association appropriate to do this work because we had already been able to carry out two similar reconstructions in Bereg and Felsőzsolca; we also showed our completed works in Bereg to the victims as encouragement. From our association, about 30–40 people worked on the reconstruction—we were a group of people sharing the same values and norms, which proved to be very important. In my time, military service was still compulsory. It was like hell on earth, but it still taught me something: that we are not supposed to think about the order but to execute it. In a disaster situation, this kind of behaviour made us suitable to be able to do our work in conjunction with a semi-military organisation [the Disaster Management Directorate General]. The image of the houses could be adjusted to the surrounding environment exactly because we knew from experience that

with traumatised people we do not experiment. It did not occur to us to try out the latest architectural trends on them. We could not do that.

What we were thinking about was what was inside them, and it was obviously the image of the houses they grew up in. Therefore, we built houses that told stories about the world around the Somló Hill, but our plans met the requirements of a modern house, too. We decided on an American kitchen layout because a large living space expands the space and also helps the residents mentally. Based on the idea of my architect colleague László Zsigmond, we built a model house in three months, which everyone could see—that is why there was no press sensation surrounding the construction. Despite the similar forms, however, we also invented so-called intervention points. We designed the façades, porches, chimneys, and footings facing the streets together with the residents in order to make them unique to an extent because people who will live in them are also unique. I received the highest praise from the former Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Taiwan Shen Lyu-shun, who personally visited the construction site. I recited the whole methodology to him—meanwhile, he was silent and shook his head. I already thought to myself that he does not like it, but when he spoke, deeply moved, he said that even if they were to build the world’s tallest tower blocks, they would not be capable of doing what we do because they could not point the individuals, the community, and the organisation in the proper direction.

The houses have been given an image that the residents can relate to. Can the identity of the Hungarian people appear in iconic buildings today?

If I put, let us say, six different pictures on the table, I think everyone could tell which one is from which country. Why? Because there is some kind of genius loci, the spirit of a certain place, in them, something that is identical to the ethnic group or nation that lives in that certain country. The problem, obviously, comes from suppressing it and replacing it with fashion. Everyone can tell exactly when the houses in rural or suburban Hungary were built within the last forty years: in the beginning, it was the Jockey Ewing-kind of ranches on a gutter that prevailed. Then around the nineties, when the free world opened up, the cheap knockoff of terrain houses appeared as well—this type of house does not exist in the Mediterranean, only here. Then came the minimal style: square houses are rocking again because they are what people see in magazines. And this is not normal.

Architecture cannot be a fashion, because if it is a fashion, it will have very serious consequences.

In that case, none of us will inherit a house, but a problem that needs to be dismantled, and we will be left with an empty plot of land. This trick can be used to push people into extreme indebtedness, which makes them even more controllable. This is how architecture and freedom are connected.

In the past, people used to build their houses themselves. Today, many people choose a newly built home with a pre-defined layout. What kind of homes do you think will be created in the next ten years?

It is a difficult question because Hungary is going through a transition period. To the west of the Leitha River, model houses have been developed that you can choose from a catalogue and ‘buy’ in the store and all you have to do is ‘assemble’ them at home. In Hungary, we are still balancing between friends and families building together and building contractors. In most cases, if someone has a regular profession, he will get more income from it than what he would make as an amateur bricklayer. During the designing process, I myself try to give the client free space so that his ideas also appear in a well-functioning house. In the Chamber of Hungarian Architects, we strive to return to the role we had eighty years ago.

On the one hand, future Hungarian architecture must be modern regarding technology, use, and lifestyle. It must express the world in which we live in a modern way.

However, on the other hand, it must also be appropriate, expressing the identity of the place where we were born for a reason. This is our job, and this is our image.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article