It is clear now that the enormous social and political transformations that took place in South Africa after apartheid ended did not bring about the liberal utopia the world was expecting it to become. Instead, under ANC leadership, the country has a good chance of becoming a failed state, while even after thirty years, misgovernance is often blamed on the white Afrikaner community, whose lives and livelihoods are threatened by racial violence, double standards and open discrimination. At this year’s CPAC Hungary, I interviewed Ernst Roets, Deputy CEO of AfriForum, the biggest civil rights group in Africa fighting for the survival of the Afrikaner community by building institutions and assuming responsibility.

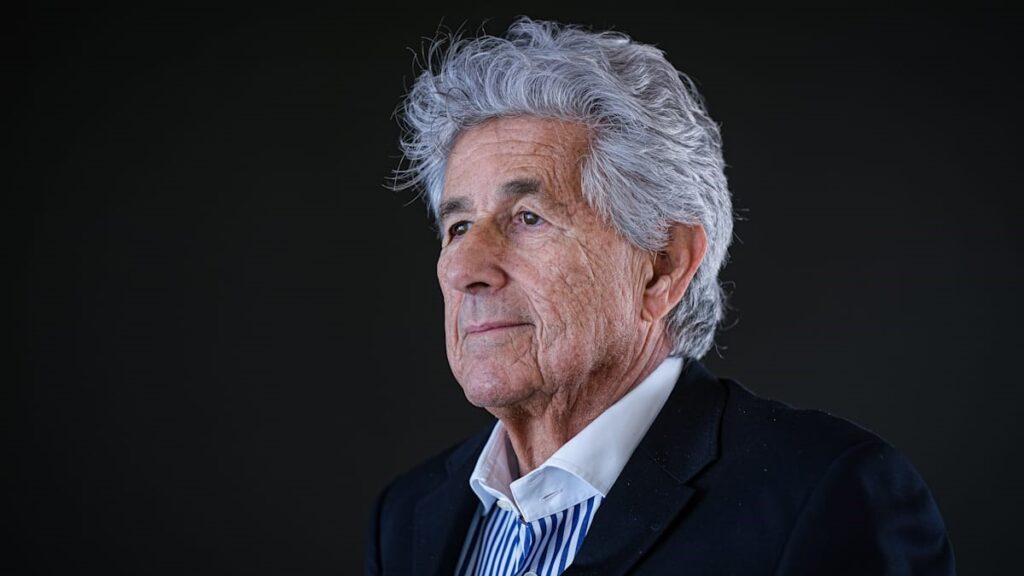

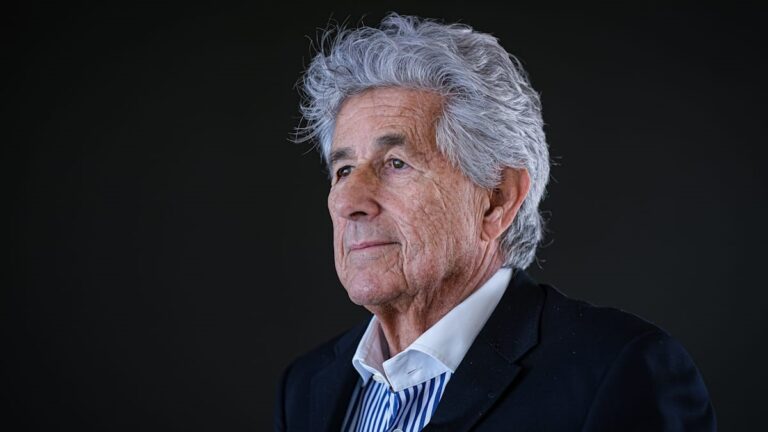

Although sympathetic to your cause, Hungarians know little about South Africa. Could you please share with the readers some details about AfriForum? It is quite large an organization, yet it is constantly branded as a far-right extremist group. What is the truth?

AfriForum is a civil rights group in South Africa, within the Afrikaner community. Although we’re not exclusive, so anyone can join, we have a particular focus on the Afrikaner community, and we now have 301,000 members. To be a member, you have to make a monthly, financial contribution, so it’s not just signing a petition. And this makes us the biggest Afrikaner organization in history, but also the biggest civil rights group on the African continent and in the Southern hemisphere. I don’t know about any other civil rights group (in other words, pressure group) outside party politics in Europe that have that many members. We are very large, and we believe in traditional conservative, Christian values, and in promoting mutual recognition, respect and peaceful coexistence.

And so we do a lot of work with local communities in South Africa–black communities, traditional communities–continually. But that doesn’t get reported that much because it’s not newsworthy and not controversial. But I think it has become very hard for the South African government and the media to paint us as extremists because we just don’t fit the description. We are way too big to be an extremist organization. We have way too much support and we are just not extremists. We actively work with black communities on a regular basis. But yeah, if you say something that’s conservative and if you criticize what the current government is doing, you tend to get that label.

Do you think you can make a difference outside traditional party politics?

We have a joke in South Africa. When people ask us why we don’t become a political party, we say our aspirations are much bigger than that. And actually, Prime Minister Orbán also said this morning that politicians come and go all the time, but institutions span over lifetimes. And that’s why we are building institutions in South Africa. You will not make any difference through party politics because of our history and because of the history of the ANC (the ruling party) because it’s the party of Nelson Mandela. Even though people are extremely angry with the government which basically just does nothing, they still keep voting for them out of loyalty to Nelson Mandela and out of loyalty to the history of the ANC–and also out of this perception that South Africa was this evil place, which was then liberated by the ANC. So people just keep voting for them. Eventually, they will lose an election in the future, but we are just a minority community and South Africa is big. South Africa is basically the size of Europe if you take away Spain. It’s like saying that Hungarians have to try to win a European election. Therefore, our approach is to build institutions that ensure that our community can have a future.

What is your personal motivation dedicating your life to the Afrikaner community? Have you ever experienced discrimination or political violence on a personal level?

I have experienced that, but that’s not my motivation. But in terms of experience, I grew up on a farm in South Africa. If you ask me how many people I know personally–like friends and family–who have been attacked or who have been murdered on farms, I think the answer is 12. That’s how many. I have had friends of mine who went to school together and who have been murdered on farms. My father’s aunt was murdered. She was stoned and then they pierced a pitchfork through her neck, that’s how they kill there. And I could go on because I know many, many such people, but that’s not what my personal motivation is. It may be a longer answer, but to put it simply, it that what I think makes us such a unique nation.

I think there’s a lot of correlation between the Afrikaners (or the Boers) and the Hungarians. When the Enlightenment and the French Revolution happened in Europe, we were in Africa hunting elephants and killing lions, so we missed that. This explains a lot. And we also had some very big wars to fight. Wars of survival. And in one particular battle–the Battle of Blood River–we were 300 against 12,000. And we made a vow that if God protects us, we will build a church and commemorate that day as a Sunday forever, for our descendants as well, regardless of which day of the week it is. So, we were attacked and we eventually won that battle, without losing a single person. The reason why I’m saying this is that it also explains why we’re so religious. Religious and conservative. We are sort of, as someone said to me, like an experiment. You send the Europeans to Africa and then Europe goes on with the Enlightenment, the French revolution, the European Union, and wokeness, and then you compare the two. Just like a sci-fi experiment. So, that’s why we are way more conservative than most of Europe. And to answer your question, what personally motivates me is the knowledge of the fact that my ancestors have done so much and have gone through so many sacrifices and it would be a shame not to try to do the same for my descendants. And I know it sounds like a cliché, but that’s really what motivates me.

We are sort of like an experiment

Undoubtedly there is discrimination against whites in South Africa, as you mentioned in your speech, sort of like a ‘reverse apartheid’ with over a hundred racial laws currently in force. Why do you think the world seems to be completely deaf to the problems of white South Africans?

Well, I think it’s largely due to political correctness, as well as disillusionment or refusal to concede to the truth. I’ll try to explain what I mean. So, the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and during that time this ‘end of history’ thesis (popularized by Francis Fukuyama) became quite well-known. It claimed that liberalism is the future and that socialism has been destroyed. And then South Africa was sort of the first major experiment. The negotiations in South Africa started in 1990, just after the Wall fell. And the idea was that now we’re going to prove to the world that we can make a place like South Africa a liberal democracy. And to concede that South Africa is not working is basically to concede that the end of history thesis–that we are all going to become liberal eventually–is not working.

And I don’t want to say this, but it is part of the story that there is unfortunately a racial dynamic as well. It’s easy to speak out against the oppression of black people, but it’s taboo to speak out if the oppression is the other way around. So, we do feel in a way deserted. By, for example, the Americans and the Dutch, who placed a lot of pressure on South Africa to adopt this new system, and now they’re just absent. But the point is–and that may also apply to our conservative friends around the world–that we can be angry about that, but it’s not going to help to just sit and just scream discrimination and oppression. The way to get out of this is just to work harder. We could be angry with other countries, but instead, we’re trying to build relationships in America and the Netherlands – and even in Hungary.

How do you see the future of white South Africans in a hundred years?

Well, it might be that there are none left, but I don’t think that’s going to happen. I think it’s difficult to say what’s going to happen in a hundred years, but if I had to guess, I think it’s going to get worse. The South African government is like an injured buffalo in the sense that it’s at its weakest and therefore it’s at its most dangerous. So, I think there are some difficult times ahead. There’s now talk about introducing a race tax, under which white people would have to pay more taxes than black people. That’s an actual political discussion that’s happening in South Africa right now. And I think as the government keeps failing, they have to blame the Afrikaners more aggressively for everything because otherwise they have to concede that they’re not a good government. And that will likely lead to more violence. I think the government’s going to deteriorate and that’s ironically the good thing. Our government is actually very totalitarian. It thinks that Joseph Stalin was a good guy, Robert Mugabe was a hero, and what happened in Venezuela is not that bad. That’s what they say. But the good news is that even though they would like to control every aspect of society, they simply can’t because they are so incompetent. So, we have a government that wants to control everything, but in reality, they’re just becoming more and more absent.

We sometimes joke and say that it’s like an anarchist utopia and that we are moving towards a point where we might not even have a government. And the point is that that’s why we put so much emphasis on building institutions because we can’t depend on a government like that. We can’t depend on our kids going to state-run universities in the future because they’re not going to be there or no one is going to accept or credit them. So, we have to build our own universities, which we’ve done. We’ve actually built two higher education institutions, which are privately owned by the Solidarity Movement of which we are part of. One is Akademia, which has about 2,500 students right now and the other one is Solt-Tech, a technical college. And we have our own media and cultural organizations as well. We have a network of 25 organizations or more, the last time I checked.

We can’t depend on a government like that

Speaking from a lifetime of experience, if you could give any advice to the West in general, what would you say to make sure that it does not go down the same path as South Africa did?

Well, there’s probably a lot that you can say, but the one is just to get back to reality and to get back to the communities and institutions. For Americans, I would say read Democracy in America (by Alexis de Tocqueville), which I think is one of the best books on politics, because his whole conclusion is that freedom does not mean ‘do whatever you want to do’. That might just as well be slavery. Because being addicted to something is slavery. So, freedom is something that you fulfil through your community. And I think this not only applies to the left, but to the right as well. Some people tend to think freedom means everyone should just do whatever they want to do. And I don’t think that’s a sustainable way of freedom. But from a more South African perspective, my advice would be that culture matters much more than what people would like to admit. I think that would be the one thing that we all ought to keep in mind.