The 2025 Belém UN climate summit (COP30) was a turning point not so much because of its ambitious commitments but rather because of the reconfiguration of power dynamics in global climate diplomacy. The conference’s mixed outcomes, the United States’ federal-level absence, and China’s increasingly assertive international posture signal the onset of a multipolar and fragmented era in climate diplomacy. The traditional Western climate bloc—led by the US and the European Union—has weakened, while the technological and financial centres of gravity are gradually shifting eastward.

Mixed Outcomes of COP30 in Belém

In November 2025, the Brazilian city of Belém hosted the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Geopolitical tensions and the United States’ unprecedented federal-level absence had a substantial impact on the dynamics of the COP30 negotiations. Deep divisions among Parties hindered decision-making until the very last moment.

The Belém Political Package, adopted at COP30, does not include roadmaps for phasing out fossil fuels or for halting and reversing deforestation, causing significant disappointment among countries advocating for more ambitious action. The text was softened primarily due to the resistance from oil-exporting nations—mainly Saudi Arabia and Russia—as well as several major emerging economies, including China and India. Nevertheless, the final decision commits to at least tripling adaptation finance by 2035, to introducing a new mechanism to support a just transition, to establishing a two-year work programme on climate finance provided by developed countries to developing countries, and to launching several new implementation initiatives.

Throughout the conference, delegates repeatedly emphasized the importance of upholding multilateralism, and most participants explicitly reaffirmed their commitment to the spirit of the Paris Agreement. This commitment, however, was overshadowed by tensions during the negotiation process, particularly around adaptation indicators and the mitigation work programme, as the Brazilian presidency disregarded open protests from several countries. COP30, therefore, did not deliver a breakthrough on emissions reductions, but it succeeded in preserving the framework of multilateral climate policy.

Impacts of the US Absence

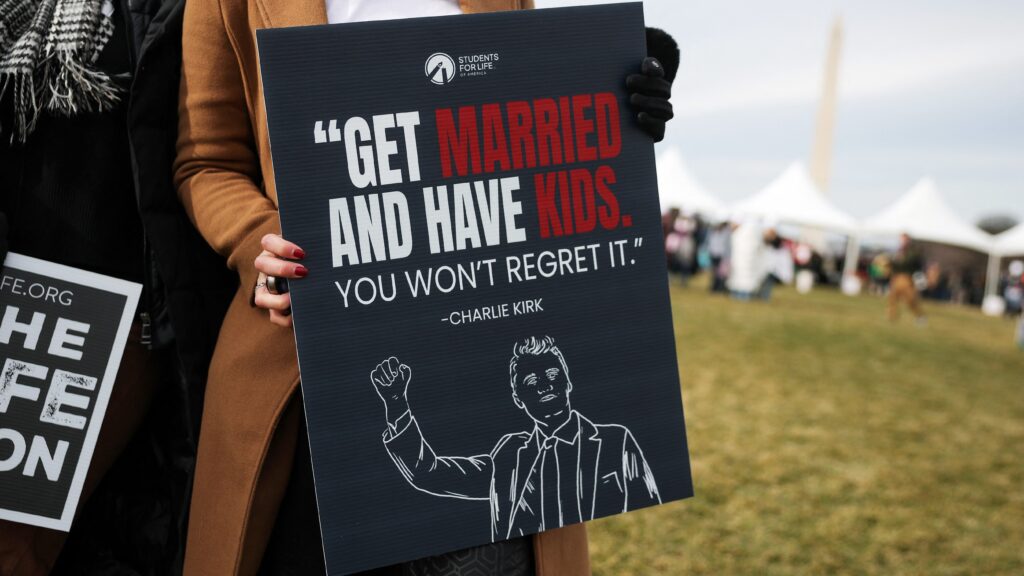

COP30 marked the first UN climate summit since the 1990s without an official federal-level delegation from the United States. The Trump administration publicly criticized the conference, issued climate-sceptic messages, and, by rejecting participation, effectively questioned the significance of the multilateral climate regime. In January 2025, Washington announced its formal withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, retreating diplomatically from the forefront of multilateral climate negotiations.

Although more than a hundred representatives of American cities, states, and companies attended COP30 in Belém, the federal government’s absence weakened the country’s traditional climate leadership role on multiple levels. First, on the political-diplomatic front, the transatlantic G7 core that had previously anchored coalitions in favour of ambitious climate goals effectively dissolved. Second, in the financial dimension, the decline in US climate and development aid further deepened the pre-existing financing gap. Third, in the normative arena, the US lost the credibility it had earned through its role in shaping the Paris Agreement and legitimizing the 1.5°C target.

‘Overall, the US withdrawal diminished the leadership role of the developed world and shifted the focus to developing countries’

The consequences of the US absence extend beyond COP30: the American withdrawal has undermined multilateralism and created opportunities for other powers, particularly China, to gain greater influence in climate policy. According to former US climate envoy John Kerry, the US has become a ‘denier, delayer and divider’ on climate change, eroding global cooperation.

At the same time, this withdrawal increased pressure on the European Union and other developed countries, whose ambitions—such as a roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels—were partially thwarted by Saudi-led resistance. Economist Jeffrey Sachs, however, noted that the federal government’s absence may have paradoxically facilitated compromise in Belém by reducing space for major political clashes. Overall, the US withdrawal diminished the leadership role of the developed world and shifted the focus to developing countries, particularly coalitions from the Global South.

China’s More Assertive Role

China, as the world’s largest emitter and a leading player in green technology, assumed a more assertive role at COP30, partially filling the void left by the US. The Chinese delegation, led by climate envoy Liu Zhenmin, actively shaped the COP30 narrative and emphasized the importance of multilateralism. China celebrated the Mutirão decision as a hard-won achievement and presented it as a sign of shared political will.

Beijing’s communication builds on a ‘responsible major power’ narrative, arguing that developed countries must bear historical responsibility while China—still classifying itself as a developing country—accelerates the transformation of its energy system without abandoning fossil fuels. It also stresses energy sovereignty and development priorities: from its perspective, focusing solely on fossil-fuel phase-out without robust renewables deployment is unrealistic and would severely jeopardize national energy sovereignty and social stability. The Chinese narrative also includes criticism of the financial and trade architecture, viewing US tariffs and certain EU trade measures as steps that undermine global climate efforts.

‘China is deliberately building its technological and economic climate leadership profile’

At the same time, China is deliberately building its technological and economic climate leadership profile: a significant portion of renewable energy investments, as well as the majority of solar panel, battery, and electric vehicle value chains, is now controlled by Chinese firms. China’s revenues from green technology exports now exceed the United States’ income from fossil-fuel exports.

However, China’s climate leadership role is deeply paradoxical: the country is still increasing its fossil-fuel-based electricity generation, and new coal plants continue to be built. Moreover, a significant proportion of Chinese climate-related finance to developing countries takes the form of loans rather than grants, which raises concerns about debt sustainability and cannot fully compensate for the loss of grant-based support from traditional donors, including the US. The China–India alignment helped coordinate debates between developed and developing countries, but it did not resolve the underlying climate finance gap.

The EU’s Engagement at COP30

With support from Latin American partners and small island developing states, the European Union emerged as one of the key players in the high-ambition camp at COP30. In the absence of the US, however, the EU adopted a more assertive stance than in previous years and held firmly to its red lines throughout the negotiations. This marked a clear shift from earlier COPs, where the EU often prioritized bridge-building and the preservation of the multilateral process, sometimes even at the expense of its own interests.

In Belém, EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra and Danish climate minister Lars Aagaard made it clear that the EU was prepared to block the final deal if mitigation was not explicitly reflected in the outcome. More than 80 countries supported the inclusion of a fossil-fuel-phase-out roadmap in the final document. As part of the compromise, this roadmap was removed from the text, but Brazil intends to develop a roadmap outside the formal UN process under its presidency. The EU thus remains a normative leader, but its geopolitical weight limits its capacity to lead on implementation and finance. Competitiveness challenges, energy-price shocks, and internal political divisions currently constrain its effective influence.

Shifts in Global Climate Leadership

After COP30, global climate governance is becoming increasingly fragmented. Normative leadership remains primarily with the EU-led coalition and vulnerable countries, which emphasize the 1.5°C Paris goal, a just transition, and the gradual phase-out of fossil fuels. However, the United States’ federal-level absence clearly weakens this bloc’s ability to assert its interests.

‘Moral leadership is increasingly embodied by the voices of small island states, as well as African and Latin American countries’

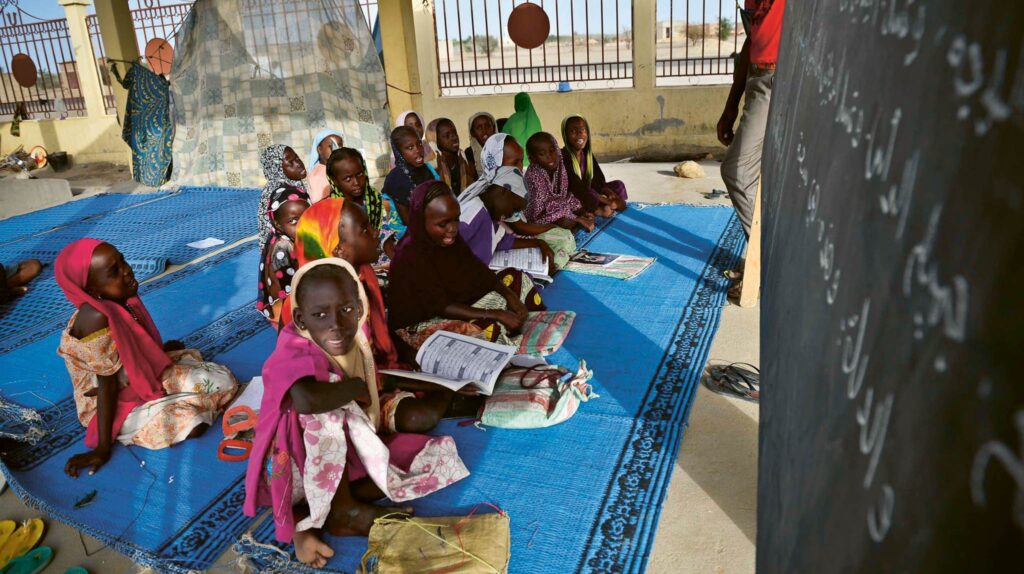

In contrast, technological-industrial leadership has increasingly gravitated toward China, which dominates key clean technology global value chains. In the sphere of climate finance, a palpable vacuum has emerged: the US withdrawal and fragmented, often hard-to-access financing mechanisms mean that, from the perspective of developing countries, G20-level initiatives still fall far short of promised levels. Moral leadership is increasingly embodied by the voices of small island states, as well as African and Latin American countries, who firmly warn that the current emissions trajectory leads toward 2.3–2.8°C global temperature rise and that the COP process alone is insufficient to reverse the trend.

Conclusion

COP30 clearly signals the ongoing transformation of global climate governance. The United States’ partial withdrawal has noticeably weakened Western influence, while China has moved to fill part of the resulting vacuum through a stronger technological presence and a more assertive narrative. This shift has strengthened developing countries’ positions in negotiations, though China has not fully assumed the global responsibilities inherent in a climate leadership role.

The key question for the next decade will be whether this fragmented climate governance system can evolve into a model of competitive cooperation, in which the EU, China, and other major developed and developing economies continue to compete for green technologies and markets while contributing meaningfully to shared global goals. Maintaining the 1.5–2°C Paris target is only realistic if discussions on climate financing and energy transition extend beyond the COP process. These discussions must also occur in parallel forums—such as the G20, development finance institutions, and regional alliances—and be grounded in substantive, constructive collaboration.

Related articles: