This is an abridged version of the original interview published in Magyar Kurír on 18 December 2022.

When I recently asked Father Iván Csete, who celebrated the festive Mass for the 120th anniversary of the New York St. Stephen’s Hungarian Catholic community, about who could share the history of the community, he recommended Katalin Votin. She hasn’t only been an active member of this community for over 30 years, but has also played a leading role in several Hungarian organizations for many years. Our conversation revealed a winding journey of individual, family, and community life that had once seen better days.

***

From Zala to America

When I asked Kati my usual opening question about how she came to America, I heard a surprising story. Her grandmother, who lived in Zala County, Hungary, took her photograph to a friend in another village. The friend’s son, who lived in America, liked the photo so much that when he visited Hungary in 1969, he sought out Kati in Keszthely. They got to know each other and soon married. Mihály returned to America, and six months later, Kati emigrated to join her husband in New York, where they lived together for 48 years, until his passing on Christmas Eve 2014.

‘I have a photo album with about 30 pictures of all the women my husband tried to court before me—it’s an honor that he chose me in the end,’ she laughed. ‘I was tall, slim, blonde, and blue-eyed—his preferred type. I had to think carefully about what to do with his offer, but I was a brave and adventurous young woman, so I said yes to him. What brought us together was our love of nature. In college, I often hiked in the mountains, and he loved the mountains too—he came from a small mountain village, which he often told me about,’ Kati said.

Her husband attended high school at the Piarist school in Nagykanizsa and later studied in Miskolc. Due to his involvement in the 1956 revolution, he wasn’t admitted to the Budapest University of Technology, and knowing that he wouldn’t be able to get a proper job, he fled the country with one of his younger brothers in 1957, heading toward Austria. They were caught twice and even imprisoned. Years later, his future wife attended college in Budapest, directly across from the Markó Street Prison where they were previously incarcerated—symbolically intertwining their fates before they had even known about each other’s existence. The brothers eventually reached Yugoslavia by swimming across the Mura River. ‘They were both athletes, that’s how they managed such a daring escape. Later, when we visited Hungary, he showed me that part of the Mura River. It’s an ugly, swirling, fast-flowing river. I didn’t like it much.’

Mihály had been unable to complete his mechanical engineering studies in Hungary, but he continued his education in America and found work as a tool design engineer at Ideal Toy, a toy manufacturing company. He was the one who translated Ernő Rubik’s first letter regarding the overseas introduction of his famous cube.

‘The brothers eventually reached Yugoslavia by swimming across the Mura River’

Before moving to America, Kati had already traveled abroad—a rare privilege at the time. She studied French and Russian in high school, German in college, and even Esperanto through her sports club, which enabled her to take part in hiking trips, including some abroad. As a college student, she participated in a work exchange program in Germany. In America, she worked in the garment industry as a pattern maker. She recalled that in the 70s, patterns were still made by hand in the U.S., whereas in Hungary, students were trained in industrial garment production by that time. To catch up, she attended multiple professional courses, including English and shorthand, and enrolled in a five-year evening program at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) while working. 27 years later, she returned to the same school to study computer science. She also studied fashion design—and designed skirt pants as an alternative to the mandatory skirts for Girl Scouts and even sewed scout uniforms for her daughters.

The Golden Days of Hungarian American Life

Kati grew up in a religious family and attended not only church, but also religious education classes, which were more tolerated in rural areas than in cities during the Communist regime. Even as a college student in Budapest from 1965 to 1968, she continued going to church, which was uncommon by that time in cities. ‘I lived near the church at Béke Square, but I also regularly went to the Basilica or whichever church was along my way’, she explained.

Before their children were born, she and her husband often spent weekends at his brother’s house in New Jersey, where they attended Mass and Hungarian events at the Woodbridge Hungarian Catholic Church. They rarely visited St. Stephen’s Hungarian Church in New York, as it was too far for them, and they worked a lot. The same was true after their children were born. Their first daughter was born in 1975, followed by two sons and another daughter. They lived on the outskirts of the city in a semi-rural area. While Kati worked, her sister-in-law cared for the children, ensuring that they grew up in a Hungarian-speaking family environment. However, they attended the local American Catholic school and church, where they also went to Mass and religious education classes.

They first learned about the New York Hungarian weekend school and scouting through the local Hungarian radio station. Interestingly, even though they attended the local church together with other Hungarian parents whose children went there, no one had invited them to join. Her husband explained this awkward situation by the divide between the so-called ‘DPs’ (Displaced Persons)—Hungarians expelled or forced to flee the newly-introduced Communist regime during the post-war years (1944–49) and those who arrived later. Many of the DPs remained in Austria or Germany, while those who emigrated to America initially formed the Hungarian scouting movement and founded the Hungarian School in New York in 1963 under the leadership of Imre Beke and Szabolcs Szekeres. By the end of the first academic year, the school had eight classes with 107 students. The DPs, however, strongly distanced themselves in the 60s from the refugees of the 1956 revolution and freedom fight, and—according to Kati—didn’t feel a responsibility to welcome and involve those Hungarians into their communities who arrived later. This divide was so deep that for some time, even two separate Hungarian weekend schools operated simultaneously, competing for students.

‘The DPs, however, strongly distanced themselves in the 60s from the refugees of the 1956 revolution and freedom fight’

Despite this initial divide, in the 70s and 80s, the Votin family joined the Hungarian community, motivated by learning the Hungarian language and scouting experiences to be provided for their children. The school, which typically had 45 to 75 students, was closely linked to the St. Stephen’s Church. The last Franciscan friar, Father Domonkos Csorba, strongly supported them—he kept tuition low and mediated conflicts between the English-speaking and Hungarian-speaking members. The scouts also had a close relationship with the church—they were allowed to hold meetings and celebrations there, and scout leaders required children to attend the Hungarian school.

The First Winds of Change

After the Hungarian Franciscans left, Neil O’Connell, an Irish priest, unexpectedly and significantly raised tuition fees. Citing a lawsuit related to a Hungarian event, he also demanded that individual insurance policies be taken out and hall monitors be assigned. Events could only be held under strict conditions, requiring much more effort from the organizers, and state offices didn’t make their work any easier.

In 1987, Kati joined the Hungarian Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), which financially and morally supported the Hungarian school and scouting program. Eventually, she served as its president for a long time (from 1990 to 2012), tirelessly handling administrative matters beyond her working hours and family responsibilities. The Hungarian school faced frequent leadership changes and constant financial difficulties—tuition fees covered less than 65 per cent of its expenses. Donations from supporters ensured its survival, necessitating ongoing creative fundraising efforts, such as selling Christmas poetry collections or school T-shirts. Another major fundraising event was the Tulip Ball, held in the grand hall of St. Stephen’s Church. It was organized by the Mothers’ Association, though most often prepared by the generous cooks of the Hungarian Charity Society. The event attracted many outsiders in addition to the students’ families. Kati recalled how, in the pre-internet era, organizing such events in a vast city where Hungarians lived increasingly scattered —and have since become even more dispersed—required enormous physical effort: ‘We had to design the invitations, print them, distribute them as leaflets to Hungarian shops and travel agencies in New York, and also physically mail them to our contact list.’

Founded in 1907, the New York Hungarian Charity Society wasn’t part of the church community, but held its meetings in the church halls. Kati first heard about the organization during this time and joined with her husband, requesting their financial support for the Hungarian school and scouting program. For over ten years, they received annual donations of $1,000 to $1,500. When Kati became a leader of the Charity Society—vice president in 2009, president in 2013—they significantly increased their support for the Hungarian church to help sustain the Hungarian Masses and revive the Saint Clare Society. They also provided substantial funding to the Hungarian school, local Hungarian scouts, the Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris (KMCSSZ), and the Hungarian House, while offering smaller contributions to other Hungarian churches—two Reformed, one Baptist, and one Greek Catholic.

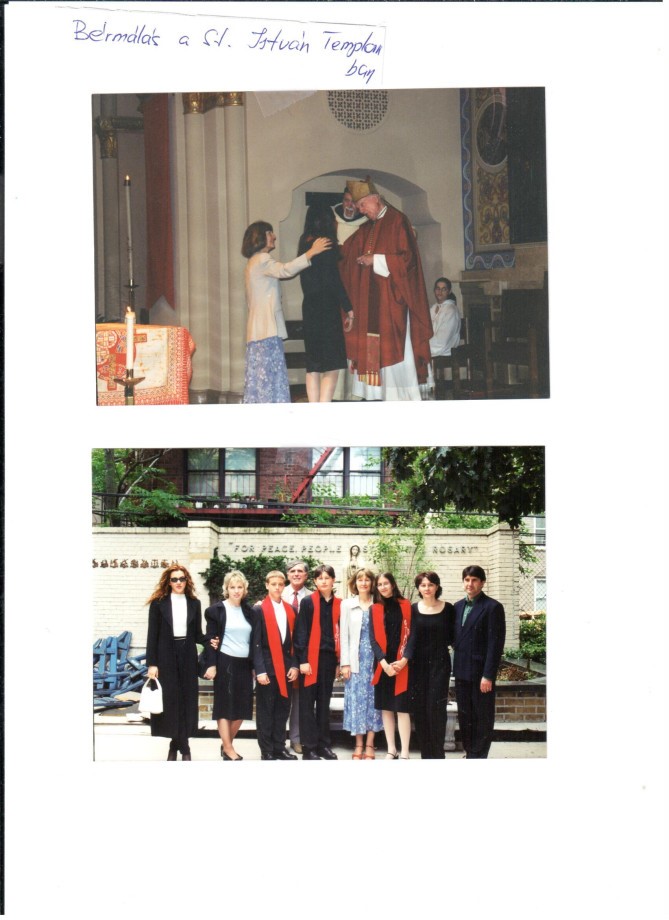

They regularly organized grand Christmas celebrations at St. Stephen’s Church, where every child—sometimes as many as a hundred—received a gift. Yet, from the early 2000s, fewer and fewer children and families attended Mass regularly. Even though Kati’s children had already been confirmed, she helped organize a confirmation group for Hungarian families living farther away.

In the early 2000s, Father Angelo Gambatese arrived. At the beginning, Father Angelo was very kind and supportive of the Hungarian community, never raised rental fees, and even wore the Hungarian school’s gifted T-shirt to promote it. Around the same time, a group of young Hungarians in their 20s arrived in New York from Transylvania (Romania) and started to attend the church regularly. They quickly won over the priest, who ‘allowed them everything’. On Friday nights, they gathered for table tennis games, sometimes attracting 30–35 people. Some even held their weddings at the church. There were also various activities, such as silk painting, and for a few months, visiting Franciscan monks gave lectures, too. The Lay Council maintained a decades-old tradition of organizing popular street fairs in front of the church, where they sold Hungarian food and secondhand goods to support the church. The scouts entertained children in the parking lot. However, in 2008, a serious conflict between Fr. Angelo and this young Hungarian group led to the end of youth gatherings, and the 2015 church ‘merger’ ended the street fair altogether.

After the Church Closure

Kati reveals how grateful she was that her husband’s memorial Mass was held in April 2015, as the church was full—something increasingly rare at the time. Because the couple was well known, many people attended. Similarly, the last Mass in August of the same year drew a large crowd, even from far away. After what was officially termed a ‘merger’, but was effectively a closure, the Hungarian community was allowed to hold its Masses at St. Monica’s Church. However, they were treated unkindly there. For example, Father Baker had initially promised they could continue using the parking lot next to St. Stephen’s Church on Sundays, but after a few months, they were told they ‘couldn’t find the key’. Furthermore, St. Monica’s lacked a community hall, so most Hungarians eventually moved to St. Joseph’s German Church, where Father Ramsey welcomed them. Some, though, continued attending English masses at St. Monica’s.

Over time, the Hungarian weekend school and scout troops completely detached from the church, a process that had already begun before the closure. Kati had been a vital link between Hungarian institutions, but her successors didn’t prioritize this connection. She no longer knows the exact structure in which the school and scouts operate today, but apparently, there is no longer a living relationship with the church community. Currently, her youngest son is the only active scout who regularly attends Hungarian Sunday Mass, serving as the cross-bearer; her other three children and six grandchildren live far away. A few young children who attend religious education, some of whom are scouts, also come to church occasionally.

According to Kati, this leaves little hope for any positive change in the future of the church community: ‘I don’t see any support from anywhere. The local diocese will not disregard the huge mistake we made when the Hungarian church’s Lay Council representative failed to appear at the decisive meeting—supposedly because he couldn’t find a parking space and went home—leaving the Hungarian community without representation. This cannot be undone. I’m glad that today’s leaders of the Lay Council, Róbert Winer and Ágnes Perényi, are still fighting, but I don’t know if it’s worth it. Today, it was officially announced that the only printed Catholic newspaper will cease to exist—it will now only be available online. They say this is the future. Well, I don’t know…Even members of the current small religious education group, consisting of some children of the previously mentioned Transylvanian youth group and Róbert Winer’s grandchildren, will unlikely attend regularly after their first communion.’

Despite all of this, she still helps, organizing post-mass coffee gatherings. In the past, these were alternately arranged by the Charity Society, the Saint Clare Society, the Mothers’ Association, and the Lay Council. The Saint Clare Society has dissolved, and the Charity Society and Mothers’ Association are dying out. The Charity Society’s last event was its 111th-anniversary celebration in 2019; since the COVID pandemic, it has not organized anything. The Mothers’ Association now consists of only 6–8 elderly members. Today, post-mass coffee gatherings are primarily organized by the Lay Council, which consists of 18–20 people who still regularly attend church.

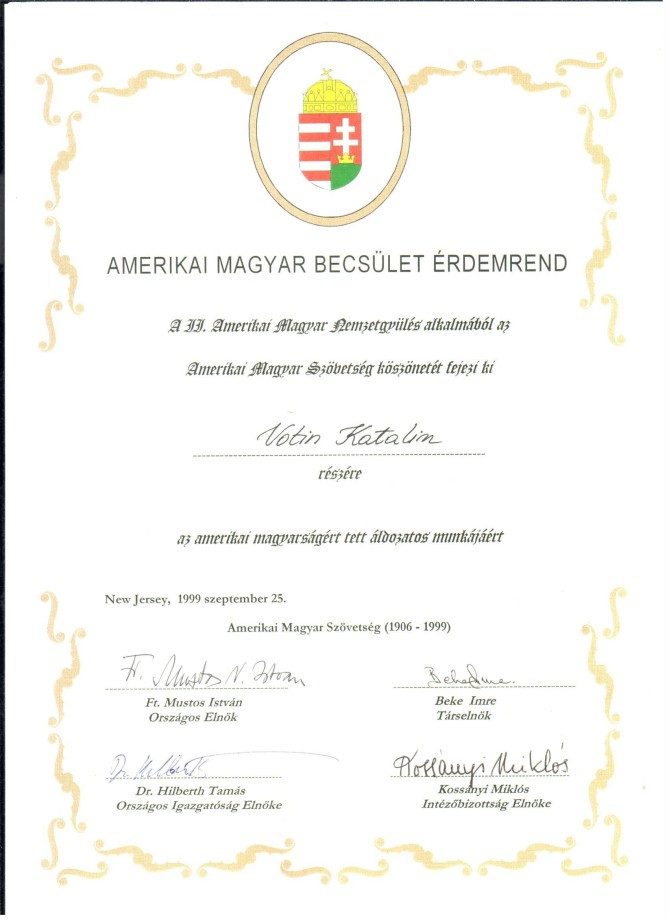

A Lifetime of Dedication Recognized

In 1999, Katalin received the Hungarian American Order of Merit from the American Hungarian Federation in recognition of her dedicated service to the Hungarian American community. Dr. Tamás Hilberth, the organization’s president at the time, presented the medal at a grand event attended by all the local scout troops, schools, and associations. ‘I deeply appreciate it, especially now as I look back on the past 32 years. I weighed all the books and folders from which I selected pictures and documents for this interview—16 kilograms! It’s both a sad and joyful, yet proud feeling to know that I accomplished all of this,’ she concluded our conversation.

Read more Diaspora interviews: