In his book My American Roadtrip we get to know András Ludányi, born in 1940 in Szikszó (Hungary) as the third child of Colonel Antal Ludányi and Erzsébet Ludányi Prileszky, who grew up in America, but as a child experienced the difficulties of fleeing Hungary in the post-war era, the atmosphere of the refugee camps in Austria, and the challenges of arriving and settling in the New World. Moving on from a farm in Virginia, with the help of caring family members, he eventually embarked on a rich and varied professional career as a university teacher and active member of the Hungarian American community, and built a happy family life before moving back to Budapest in 2010. In the interview I asked him about topics I felt he had left out of his book.

***

It seems to me that you inherited a lot from your parents, which is reflected in your self-critical yet peaceful personality and your critical yet accepting attitude towards the world. How do you see it?

My mother was a very tough woman who endured a lot. My father too, but he had poorer health. Neither of them learned English very well; my mother did not want us to speak English with her, so we only spoke to her in Hungarian—that was her strategy. We knew she could speak English, because when she went shopping, she explained very well what she wanted. She was the one who really kept the family together; my father could not do it after a while because of his stomach cancer, which ultimately took his life, but he worked a lot to support our education. I am proud of him because he was able to cope with the physical and psychological difficulties of having to adapt to people who were not on his intellectual level—similarly to many other DPs (‘displaced person’) and 1956ers. Because of their perseverance and their fantastic diligence, love of family and country,

our parents remained very strong role models for us.

There was another important thing that became an integral part of your personality: scouting.

Scouting had a fantastic impact on the three of us, my two younger brothers and myself. My older brother never became a scout; he joined the US Marines in 1954, went to Korea and Japan, so he looked down a bit on scouts running around in shorts since he was a real soldier. He, however, joined us on a few occasions to spend time with the ‘Riflemen’ (‘Lövészek’) Group, founded in 1959 by Zoltán Vasvári (‘Zolibá’), the first Scoutmaster in New York, who said: we have to prepare for combat ourselves, we cannot expect the American military or organizations to do that on our behalf. But for us, scouting was the first defining experience; as young teenagers, we clung to it. After 1956, of course, there were the demonstrations, which I attended with many of my scout friends, and after the revolution was crushed, we welcomed and supported refugees in the Camp Kilmer refugee camp in New Jersey. Zolibá kept his group—covered by an excellent documentary film released in 2017—alive until the late 1970s, but I was no longer able to be physically with them during those later decades.

In relation to your forty years as a university teacher (Ada, Ohio), what I remember the most from your book is that you took students ‘out in the field’ a lot. Why was this important to you?

I think a teacher should be an active participant in the lives of his or her students. Yes, we went to Toledo (Ohio) a number of times on a project, visiting the Hungarian neighborhood there and interviewing not only Hungarians, but also locals of Slovak and Polish origin, and we even produced a documentary film titled Urban Turf and Ethnic Soul, which László Mihályfi and Péter Újvági helped direct. I was able to involve my students very well in this project. The other big project I would mention was the Model UN Programme, where we simulated debates, which required learning about the foreign and domestic policies of a different country each year and how that country dealt with a crisis situation in the UN. We usually represented smaller countries, because we were a small university with a small budget, and it was quite expensive to take a large number of students to New York for a week. It now seems to be dying, not because I am not there, but it has become more and more expensive. The UN model itself may survive, but smaller universities may have to give up on the program because of their tightening budgets.

It seems to be very effective, and a niche in terms of political debate culture. It was also a kind of preparation for lobbying, which you later taught and put to good use, right?

Yes, it is a very effective program, also in the sense that we had to discipline ourselves. Almost every time while in New York, we were also invited to the UN embassy of the country we represented where we spent an hour and a half with real ambassadors, real policy makers, during which they explained to us why they represented their country the way they did. So it was a great learning opportunity. And we were able to get involved with Hungary, too: we represented Hungary at least twice. At those occasions, we met Hungarian representatives to the UN, but this was before the change of regime in Hungary, so these were ‘interesting’ people and encounters. In terms of putting these skills to good use, with the Hungarian Communion of Friends (MBK) founded in the 1970s, we first tried to get involved with and support the Hungarian Human Rights Foundation (HHRF). The lobbying itself was done by László Hámos, Jenő Brogyányi, Bulcsú Veress and a few others, for example Emese Latkóczi. They were the active, inner core; the other organizations, like us, were more locally important: we were active mostly in Ohio, for instance. The Ohio senators at the time were very influential in Romanian–American relations; for example, Howard Metzenbaum was an important senator, and we were able to lobby with him personally.

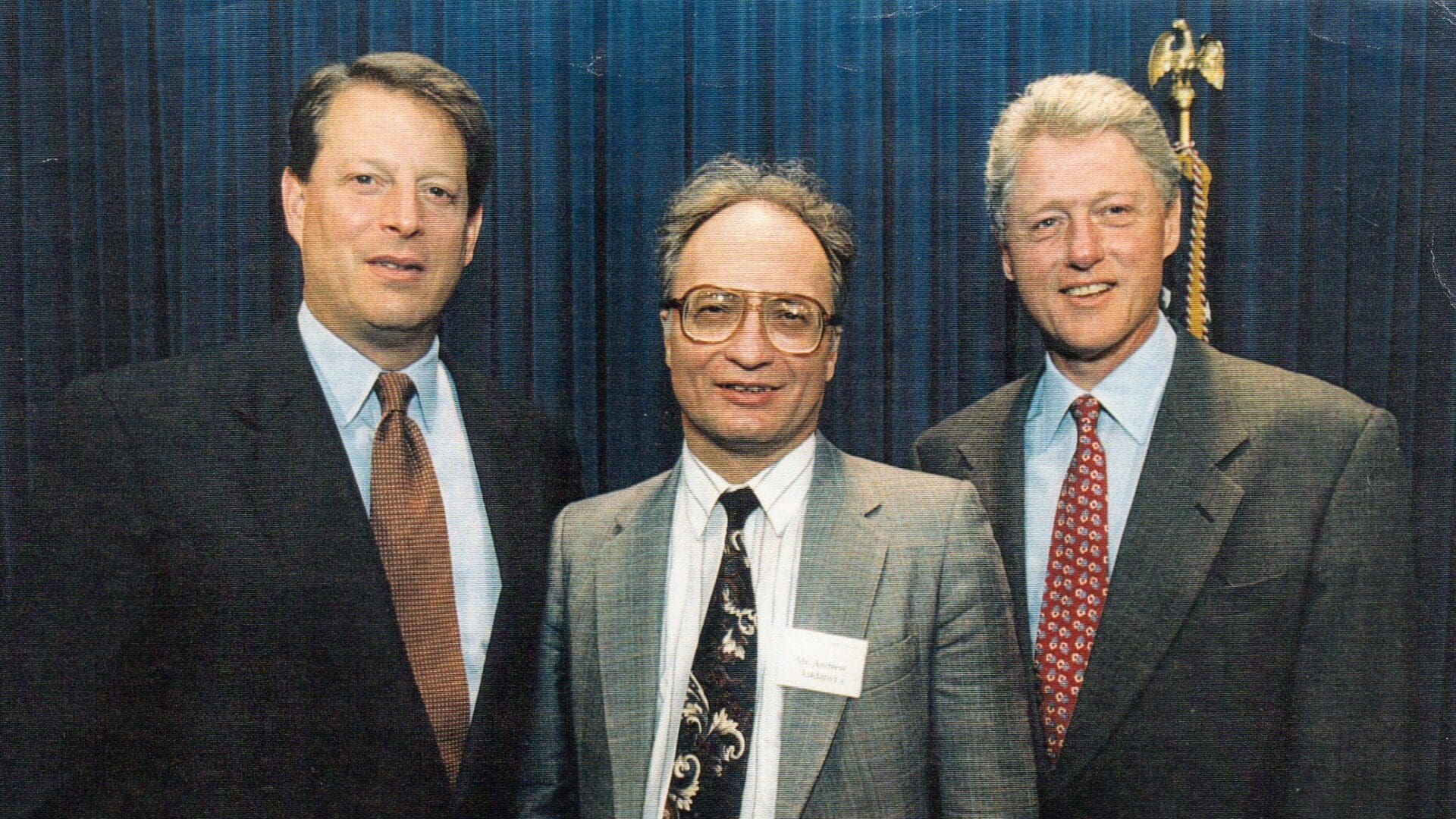

In the meantime, MBK and the newly formed Hungarian American Coalition (HAC), which I also helped found, began sponsoring human rights workshops at the time of the regime changes in Central Eastern Europe, because we were beginning to worry that HHRF was so overwhelmed that it would not have time to develop human rights activists in the American art of lobbying. The first workshop of this nature was held in 1989 in West Virginia, the next in Washington DC, combining learning opportunities and group discussions with direct participation in the political process, in the form of hearings at the Capitol and the Hungarian Embassy. During the 1996 presidential election campaign

we were also involved in lobbying in Wisconsin that led to Hungary’s NATO membership.

You often wrote positively about Democrats in your book, but said nothing complimentary about Republicans, even though, as you also write, ‘your family background and your DP status would have automatically made you into a staunch Republican’. Why has your attitude changed so much?

This is not entirely true. Traditionally, only the old working-class Americans who emigrated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were Democrats, who got involved in the labor movements during the New Deal era of the 1930s and for whom supporting the more socially sensitive Democrats was natural. The DP generation and the 1956ers, on the other hand, typically strengthened the Republicans during the second half of the 20th century because of the negative legacy of Yalta. The refugees who arrived in these waves often never learned English very well, but their children did, and could use it politically. László Hámos’ writings and his White House hearings reflected how effectively they were able to support the Hungarian case. Therefore, some of us consciously decided that, although we cannot fully connect emotionally with the Democrats, it is important that they have Hungarian representation. Hámos himself preferred to join the Democrats because he logically saw that

in the late 1970s the Carter administration considered human rights much more important

than the Republicans.

Were you affiliated with them for the same reason?

Yes, although I had another issue that led me in that direction: the Hungarians in Toledo. Péter Újvági was very active in the Democratic Party; so much so that during presidential elections, Democratic presidential candidates always stopped in Toledo to campaign with him. They knew that there was a ‘Hungarian Birmingham’, which was not entirely Hungarian, but was populated in large part by Central European immigrants and their descendants, 90 per cent of whom voted Democrat. Consequently, Péter Újvági had much more influence than other Hungarian American leaders in the 1980s and 1990s. And he was ‘comfortable’ with the human rights issue—that was the main reason why I was willing to get involved in this work until the arrival of the Obama administration. During his first presidential campaign, we created a brochure with Louis Kossuth’s message included. But there was a tragic break: Hillary Clinton became Secretary of State. We could no longer convince her and her circle that we were right; instead she was convinced by another circle, the financial aristocracy, George Soros and the big money, and as a result she pursued a terrible foreign policy that unfolded in North Africa as the ‘Arab Spring’, and which we have all been facing the consequences of ever since. I have not been involved in any Democratic Party activities since then.

I understand the ‘tragic break’, but I found no indication in your book that you had any positive connection with the Republicans. From that, it seems like you wrote them off completely…

This is again only partially true. In the international arena Republicans serve American interests; just like Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who evaluates world politics in terms of Hungarian interests. Protecting minority rights does not really fit into that world view. When we went to lobby the Republicans on this issue, with the exception of a few cases, we were only patted on the back, if we were listened to at all. The elder Bush listened to us a bit more, his son not so much. Back in the early 1990s, when József Antall visited Washington DC, we tried to organize ourselves to better represent Hungarian interests, but we only really did that later with HAC. Zsolt Szekeres and Edith K. Lauer were the key players there, but the MBK, mainly László Bőjtös, myself and a few others, were also able to get involved in that work and help mobilize as many Hungarians as possible to be present and show their interest for instance in joining NATO. I also have to admit that at the time I was more aligned with Democrats in the sense that they were more sensitive to social issues, such as the access to healthcare for the poor, etc. Consequently, I was more attracted to the Democrats domestically than to the Republicans. Sometimes the political personalities of the latter were not necessarily the most sympathetic either. For example, I liked the old Bush, but not the young one. But I say the same about the latest and current administrations: the most recent Republican president (and current Republican frontrunner in the presidential election campaign) has personality traits that do not impress me in the most positive way. But even so, he is a hundred times better than the current Democratic president. The latter was sympathetic to me when he was young, but since he became vice president and then president, corruption has completely saturated him and his administration. His son and his affairs are a total personal tragedy and disaster, too. Just one example from his politics: the way they have failed the people of Afghanistan is a nightmare.

Many say they have failed not only the Afghan people, but also their own. In your book you explain how America’s image has changed, and this process did not start with Afghanistan.

Indeed. America’s image has been steadily deteriorating, but it has slipped terribly in the last few years. These days, big agribusiness, pharmaceutical companies, or any large economic conglomerate have more influence on America’s domestic and foreign policy than the political parties. Parties are economically manipulated. This means that there is a deep state, which is not a single actor, but the combined power of these interest groups—for example, the big oil companies in the Middle East—without which it is impossible to imagine American foreign policy today. A similar phenomenon is visible relating to Ukraine, where the agricultural and reconstruction interests are controlled and pursued by some big multinationals. And their interest is not necessarily America’s interest. In the 1950s, the Secretary of Defense in the Eisenhower administration said: ‘What is good for General Motors is good for the United States’. But that is no longer true. After World War II, America has gradually become more and more unpalatable to the outside world. The Achilles’ heel of American foreign policy is that they can no longer decouple the influence of big interest groups. This will be tested again in the next administration. In any case, I cannot vote for the Democrats any longer. My wife and I are otherwise dual citizens; we can vote here and there.

Speaking of ‘here and there’ (’itt-ott’ in Hungarian) , let’s get back to the MBK and the ITT-OTT camps. Why was this community founded and what has changed since the regime change of 1989–1990?

What is happening to ITT-OTT now is very sad, but not unique. If I have to put it in the shortest possible way, the MBK came into existence because in the 1960s-1970s, some of us realized how fragmented the Hungarian American community was, and we realized that in order to avoid rapid assimilation we had to become so-called diaspora Hungarians. The change of regime brought a big break: the attendance of the ITT-OTT camps of 150 to 200 people suddenly dropped to 120, then to 80; last year there were only 30 of us. This reflects partly the fact that many Hungarians still lived in America with an émigré vision, that is, if things changed at home, they would no longer have to go to Lake Hope to camp, but would go home to Hungary for a visit. And also that the kind of togetherness and intellectual ammunition that our camp provided was no longer necessary. And that change was very hard to digest. As Tibor Cseh writes, if we lose the Hungarian language, our affiliation becomes only the weekend picnic going forward, which means that at best only Hungarian folk dancing, music, and gastronomy will remain. To reduce Hungarian identity to those is a terrible self-betrayal.

Literary roots must not be abandoned, they must be preserved somehow;

there are so many technical possibilities nowadays, but there are not enough channels of this kind available. For example, I sent my brother an audiobook of Wass Albert’s Thirteen Apple Trees and he is so happy to listen to it, even though he was not really interested in Hungarian literature before as he could not read Hungarian well enough. But now he is very grateful for the audiobook. Anyone can do that. Another example is that I recorded my mother’s voice telling stories to her grandchildren when they were little. It is a fantastic experience that can be preserved and passed on.

What about this year’s ITT-OTT camp? Why will it be the last after 57 years?

Because there is no second or third generation left to take on the volunteer work of organizing it. We decided to close the door with dignity rather than crying. But if three–five young people in their twenties or thirties, or even in their forties or fifties, would be willing to carry on, it could still be saved. Our recent yearbooks are full of obituaries. Laci Bőjtös died a few years ago, but Balázs Somogyi is still here and I hope he will continue to be with us; and there we are, me and Péter Kovalszki, who is a little younger, but also struggling. Józsi Megyeri and Erika Bokor are only in their sixties, but they are also stretched to the limit. This year’s theme therefore will be the history of MBK. That is all I have been working on for the last two months. We must also erect a fitting memorial to my friends Lajos Éltető and Tibor Cseh. Without these two giants we could not have kept our community alive until now. I have already finished Tibor’s book and now I am working to collect Lajos’ writings. I hope I can finish these projects.