Ákos L. Nagy was born in an Austrian refugee camp in 1947. The family emigrated to the US in December1951 and settled in Passaic, New Jersey (NJ). After graduating from college, he was drafted into the US Army and served for two years. He then obtained an MBA in Finance and worked for 30 years for a New York-based multinational company. He got involved with the American Hungarian Federation (AHF, Amerikai Magyar Szövetség, AMSZ in Hungarian) in 1980 and was recently elected for the third time as the president of this umbrella organization, the largest and oldest of its kind in the United States, established in 1906 in Cleveland, Ohio as an association of Hungarian cultural and civic institutions and churches to protect their interests in the United States. Over the past 117 years, their mission has broadened to include the protection of the rights of Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin.

***

What were the circumstances of your family’s arrival to the US?

My mother (Emerencia Timcsák) was a teacher, and my father (Dr. Sándor Nagy) was a school superintendent for the Szeged school system. The school administration stayed in place until the Red Army was at the outskirts of the city in October 1944. Fortunately, my mother and my four siblings (two brothers and two sisters) were sent previously to one of my uncles’ in Vác, north of Budapest. My family had to flee with nothing and the train containing their belongings was bombed by the Allies, so we do not even have a family photo from those times. From Vác the family went to my other uncle, Gyuri bácsi’s place in Szombathely, close to the Austrian border. My father was one of nine siblings; two died fighting the Russians in World War I. My father also fought in WWI on the Italian front when Italy turned on its allies.

What were the significant experiences and challenges faced by your family during their journey as refugees from Hungary, to Austria?

The family owned 250 acres of land in Szentes, a town close to Szeged, which was lost after the war along with other real estate they owned. By the time they got to the Austrian border, they could only buy an ox and a cart. They were fleeing with a group of a dozen or so other refugee families. Many times they became scared as they could hear loud gun and machine gun fire behind them as the German and Red Army units were fighting, and it sounded like the battle was only a mile or so behind them. At some point the German army commandeered all the oxen and horses from their refugee group, and put everybody on a train, in which they travelled around Austria for about two months, without any provision of food. The only way to survive was to find some food whenever the train stopped. My brother—who was always worried that the train would leave without him while he was scavenging for something to eat for the family—said the Austrians were often very compassionate and gave them food. All the refugees had to get off the train in the city of Braunau, Austria around April 1945, before Germany’s surrender on May 7, while the German and Red Army were still fighting near the city.

What were your family’s experiences and living conditions as refugees?

My older sister almost died in Braunau as the US Army strafed the refugees from low flying aircraft. Later, they went to a refugee camp set up for Polish soldiers, who treated them well, recalling how Hungary welcomed them during WWII after the Nazis and the Red Army destroyed the Polish Army in a coordinated manner. Then they went to an American refugee camp, and finally moved to a British camp where the refuges were treated much better. The camp was located in Trefling, at the foothills of the Alps near Spital an Drau, Austria. There were about 5,000 refugees, of which about 500 Hungarian, while the rest were Belarusians, Russians, Volk Deutsch, and Croatians. The camp had public kitchens and my siblings told me that the menu would invariably consist of bean soup (without meat) for lunch and dinner. I was born in Seeboden by the way (where the closest hospital was located) in 1947, as an unplanned child: my father was 60, and my mother was 47 at the time.

When did it begin to become evident that the final destination was going to be the United States?

We had to wait in Seeboden, Austria for about six years, because the US wanted single young people and not big families like ours. While we could have gone to other countries, my father was determined to go to the United States, nowhere else. Finally, my parents’ friends from the refugee camp, Lajos and Júlia Kovács, who by that time lived in Passaic, NJ, became our sponsors.

What were your first experiences in the US?

I went to St Stephens School in Passaic, where the nuns were of Hungarian origin, and became a Hungarian scout.

We spoke Hungarian at home and my mother organized the Hungarian Saturday School at the church.

As a teenager, I attended bi-monthly classes in New York City, which was ten miles away from Passaic, where we were taught Hungarian history, geography and culture by Hungarian university professors. There were many other organizations and Hungarian social clubs where I and my friends were active. As a college student I regularly escorted debutantes at the many Gala Debutante Balls in NYC, which despite the meagre circumstances of most of the DP refugee families (‘Displaced Persons’ was a reference to the refugees from WWII and it was not an endearing term), were held at top venues such as the Waldorf Astoria, the Plaza Hotel, and son on. These families were willing to sacrifice financially to uphold these traditions. The fact is that the ‘DP’ families were not welcomed with open arms by many Americans. They were often viewed as somehow complicit in the horrors of WWII, even the Hungarians who came to America in early 1900s often felt this way. Fortunately, the 1956 freedom fighters were treated much better.

You were and you are a member of the still existing Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris (Külföldi Magyar Cserkészszövetség, KMCSSZ in Hungarian). What about the Lövészek riflery group?

Lövészek was founded around 1959 by Zoltán Vasvári, an armoured division captain in WWII who was the Hungarian scout troop commander at the time in NYC. Young men, many 1956 freedom fighters in their early 20s, joined, who felt too old to join the scouts, and did not want to run around in scout shorts. (Back then, American men did not wear shorts, except on the beach, but Hungarian Scouts did. There was a pop tune #1 on the Hit Parade ‘Short Shorts’ sung by The Royal Teens in 1957). Sometimes I had to wear scout shorts when walking two miles to the scout home in Clifton, NJ, and I recall a couple of times that fisticuffs broke out as the kids would make fun of the shorts. I was not a member of the Lövészek though but many friends of mine were: Frank Kapitány, Camille Szabó, Gábor Imrányi, Pista Csorna and Andrew Ludányi who climbed up a 50-feet pole and tore down the Soviet flag from the UN HQ in NYC in one of the demonstrations against the Soviet re-invasion of Hungary in 1956.

Many Hungarians felt that the United States was complicit in the crushing of the revolution,

as promises were made to encourage rebellion against the Communist regime in Hungary, but the revolutionaries were let down. The NYC mounted police occasionally charged into the demonstrators against the Russkies.

There is an excellent documentary film titled Lővészek / Cold Warriors that Réka Pigniczky and Andrea Rice Lauer (President of the Hungarian American Coalition, HAC) filmed in 2017. Could you please share some ‘behind the scenes’ stories related to that?

It was filmed at the Vasvári Farm in Rummerfield, PA. Zoltán Vasvári, whom we called Uncle Zoli or ‘Zoli bá’ bought the farm when he was still a scout commander in NYC. The farm was adjacent to the scout farm that Gábor Bodnár, Tibor Szadai, Lajos Bán and Frank Bodó purchased a couple of years earlier. Later, the Garfield scouts would camp at the Bodnár Farm and the Lövészek would hone their shooting and other paramilitary skills at the Vasvári Farm. I seem to recall that older NYC scouts camped at Zoli bá’s farm even after the Lövészek was formed as there was no animosity between them (several lövészek also remained active scouts, like the Ludányi boys). Around 1958, the NYC scout boys who were five or so years older than me, were camping at the Vasvári Farm, raided our scout camp at the Bodó farm at night, and while us younger scouts were sleeping, sewed our pants legs together and then started shouting ‘Alarm!’ As we jumped out of the sleeping bags, we were totally perplexed, because we couldn’t put on our pants and ‘repel’ the attack!

Were these men actual ‘Cold War warriors’ in some sense?

Up to late 60’s, organizations such as the Lövészek were common among refugees from the Iron Curtain countries, not just among the Hungarians. Their motto was ‘Death to Bolshevism’. I believe, but do not know for a fact, that these were encouraged in the context of the Cold War, in the event of a possible Eastern-Western conflict in Europe. It ended in the late ’80s, when Zoli bá died, who, unfortunately, did not live to see the liberation of Hungary from under the Soviet boot.

You did not have to use a gun in action, though you served in the army and were supposed to go to Vietnam. How would you have felt about going if you had to? Did you ever thought about it as a way to express your gratitude to the United States, as I heard from some Hungarian immigrants?

After graduating from Farleigh Dickinson University with a BA in Mathematics, I was drafted into the US Army and served two years. I, however, don’t know how to address your question about ‘feeling gratitude to the US from some immigrants’ and consequently desiring to go to potentially die or get permanently maimed in Vietnam. America has not been attacked. About 90 per cent of US college students were opposed to the war and only ten per cent understood the geopolitical situation of containing communist terror. I understood it, and was on my way to Vietnam, but do not regret ultimately not being sent there. Actually, I wanted to be a fighter pilot and was accepted into the US Air Force, but because I wore glasses, not as a pilot, but as a navigator. I was willing to enlist for six years but while the papers were being processed, I was drafted into the Army. Sometimes I wonder about it: who knows, it could have been an adventure, even though a close friend and many acquaintances of mine died there! To directly answer your question, the ‘gratitude’ aspect was not a consideration.

I was a patriotic American who answered the call and that’s it!

(Unlike a draft dodging US President who was elected twice despite that.) All three Nagy boys served in the Army: my oldest brother fought in the Korean War.

What happened in your private life after the Army?

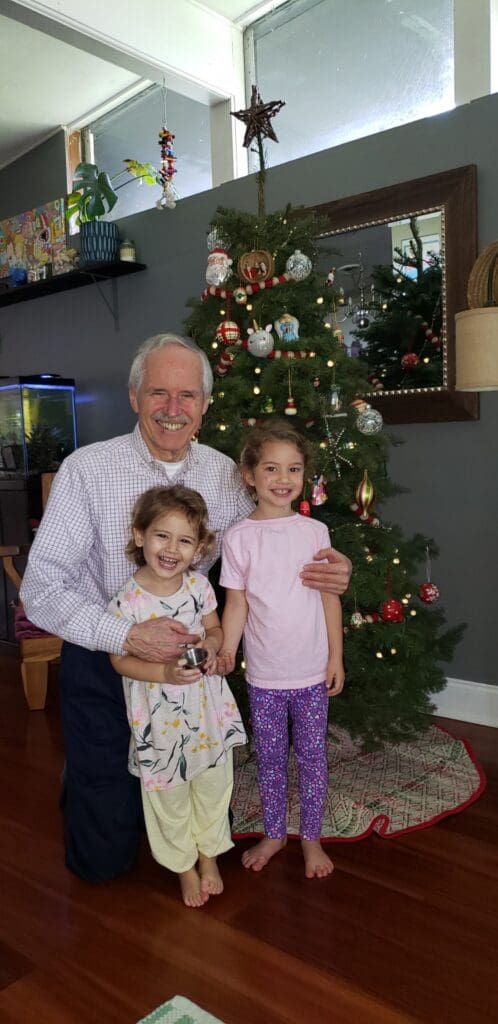

I obtained an MBA in Finance from Rutgers University and started working for W. R. Grace in 1973. I worked 28 years at their corporate headquarters, with a two-year stint at Marriott Corp HQ in Bethesda, MD. During last 20 years I managed Grace’s worldwide real estate portfolio. I am still 100 per cent active, involved in land development in Swedesboro, NJ. Last, but not least, I have a daughter, Ramona, who speaks fluent Hungarian and lives in Florida with my two little granddaughters, the apples of my eye! Our whole family is close knit maintains its heritage; my niece’s (Csilla Bányai) nine grandkids speak Hungarian and are scouts, as well as my nephew’s (Csaba Kertész) six grandkids.

And now let us turn to the American Hungarian Federation. You mentioned at a conference held in 2019 in the Hungarian Parliament that AHF’s mission includes correcting misleading assertions about Hungarians and their history. I also read on its website that one of AHF’s original missions was ‘to defend the good name and reputation of Hungary against attacks and defamations’. Is this then an ongoing mission? What are the other goals the organization is still pursuing?

AHF’s original mission was to help Hungarian immigrants to integrate into the American way of life. An expansive explanation can be found in the book entitled Emlékkönyv az Amerikai Magyar Szövetség 80. Évfordulójára edited by Dr Elemér Bakó, published in 1988. With the tragic events unfolding in Europe in WWI, WWII, and in 1956, AHF’s mission evolved. In the 1920s and 30s, much of the AHF advocacy was directed at reversing to the extent possible the evil perpetuated by the unjust and forced Treaty of Trianon, which dismembered an 1,100-year-old nation in the heart of Europe. Consequently, a new mission was added to advocate for the Hungarians living in minority status in the Carpathian basin. The third objective is to support Hungarian institutions in America so that Hungarian culture and education can flourish. These latter two are still critical goals. The AHF stands up for the rights of Hungarians living in the successor countries, and has done so for 50 years, regardless of the Hungarian governments’ positions.

We have a friendly relationship with the current government, which also advocates for the Hungarian minorities.

However, the AHF is not a lobby group; the Hungarian government has its own lobbyists in the US. AHF advocates for issues that American Hungarians feel are important. There are many articles in this regard on AHF’s website; for instance, Louis S. Segesvary, PhD, a retired American Foreign Service officer, recently wrote an article about the treatment of Hungarians in Ukraine.

Who are the members of AHF? Institutions or private individuals or both?

Currently both. The need for individuals is due to the fact that many individuals who want to work for AHF’s goals are not members in any organization. But at the outset, AHF was set up as an umbrella organization and the members were Hungarian institutions. I understand that in the heyday of Hungarian immigration to America there were 5,000 active organizations plus innumerable business ventures catering to them. My recollection is that when I joined in 1980, there were still at least 1,000 active Hungarian organizations in the US, and over 100 of them were AHF members. Since that time most of the churches and social clubs have closed, the Hungarian Reformed Federation (a fraternal insurance company) no longer exists, and overall, there are maybe 200 organizations left that have some activity.

What are the changing needs and challenges faced by the American Hungarian community today, as you’ve gathered from discussions with leaders of prominent organizations?

My understanding from speaking with the leaders of some of the large organizations is that the needs of American Hungarians have changed. This reflects the composition of the American Hungarians. Immigration from Hungary is at a trickle; most of those who come are here temporarily working for multi-national companies, and there are also many others who have overstayed their visas and live in a half-illegal status.

As a result of Hungary’s European Union membership and the eroding US economy, there is less of an incentive to immigrate here.

The net result is that the new ‘immigrants’ don’t have the same needs as the ones who arrived before 1989. If a church or club closes, it is not viewed as a tragedy any more and most of the new immigrants have family and friends to go back to in Hungary.

How are you addressing the challenge of engaging younger individuals? Could you share your strategies and successes in recruiting?

We still consider organization as key, and are actively recruiting, and forming new chapters of the AHF. We are also working on recruiting individual members. As the stalwarts who were the ‘backbones’ of these institutions are growing older, we cannot find enough younger people who are interested to get involved and sacrifice the time and effort to keep the work going. The children of the old guard often do not speak Hungarian; they may come to the large Hungarian Day in Brunswick held every year on the first Saturday of June, eat a ‘goulash’ or ‘chicken paprikash’, watch a folk dance, but that’s all, that is the extent of their Hungarian heritage. It takes up a lot of time to engage in advocacy, and people are changing, they are busy with their own lives with (non-Hungarian) social events, sports. The need to be part of Hungarian associations is not there, especially since they do not speak the language any more. Consequently, we are also discussing how to reach out to those who do not speak Hungarian but still consider their heritage important. Despite all this, we are having same success recruiting younger people: about ten are involved now as officers and directors of AHF.

AHF ‘strives to unite the American Hungarian community through work that supports common goals’. Has this also changed over the past years? What were the main issues that united them?

Supporting common goals has never been easy, as different personal, political, and ideological views needed to be put aside for the sake of a higher common goal. It worked mostly in case of bigger issues or tragedies, such as Trianon or the demolition of 300 Hungarian villages in Transylvania back in the middle of the ‘70s as part of Ceaușescu’s anti-Hungarian programmes. At that time, I was one of the founders along with Imre Beke, László Hámos and others of the Hungarian Youth Organization (Fiatal Magyar Munkaközösség or FMM). We were involved and organized protests in NYC and in Washington, DC when Ceaușescu visited. In 1976, about 2,000 people showed up at a Hungarian rally in Washington, DC to stop this attack on civilization and culture.

Even Charles, the Prince of Wales, currently the King of England spoke out against it,

stating that one of the cemeteries of an affected village contained the grave of his great-great-grandmother, Countess Klaudia Rhédey. I was a young guy and along with my friends was very resolved to stop this travesty.

In your opinion, did these protests help stop the destruction of those Hungarian villages in Transylvania?

Yes, but there’s more: these demonstrations definitely united the Hungarians not only in the US at the time. In the mid ‘80s, AHF had a lot to do with the revocation of the Most Favourite Nation bilateral trade status between Romania and the US. They destroyed Hungarian Bibles, made toilet paper out of them—those news also united American Hungarians. We received a lot of support from the Baptists, other Protestant denominations and the budding evangelicals. Reverend Sándor Haraszti was instrumental in getting the US Baptists involved as the head of the American Hungarian Baptists and later Chairman of AHF’s Board. David Funderburke, the US Ambassador to Romania in 1981, also played an important role in this effort.

Impressive… Can you please provide additional examples or actions?

Another issue that united us was the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, when all American Hungarians celebrated together the end of the communist era and Soviet occupation. AHF organized a banquet with about 500 people from all over the US in Montclair, NJ. We hosted Mátyás Szűrös, then interim president of Hungary, and after the banquet was over, Imre Beke (then Chair of the AHF Executive Committee) suggested that he should lay a wreath at the 1956 statue in Passaic Park (Clifton, NJ) which he did, along with the entire delegation from the Hungarian government. I believe this was the first wreath-laying to commemorate the 1956 freedom fighters by the Hungarian government in the world.

The latest example was the placement of the Kossuth statue in the US Capitol in 1990. Bishop Tibor Dömötör, then Chairman

of AHF, was instrumental in raising the money for the bronze bust of Kossuth, which was placed in the Statuary Hall of the Capitol in 1990. Congressman Tom Lantos was a big help getting the approval of US Congress to make this happen. Reverend László Tőkés from Romania, many congressmen and a couple of senators, and Hungarians from every part of America attended this event. There were only two non-Americans who had statues there: General Lafayette and General Pulaski (both heroes of the American Revolutionary War), and now the third and most recent is Lajos Kossuth.

Does any remnant of that gritty self-assertion still exist today?

An example of a positive resolution of an issue was the State Department’s attempt in 2017 with holdovers from the previous Obama-administration who proposed (through the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labour) to allocate $700,000 to fund media groups in Hungary that are opposing the current Hungarian government. AHF’s efforts—including a letter to Assistant Secretary of State Wess Mitchell, followed by a meeting with Congressman Andy Harris (with whom other topics were also discussed including Ukraine’s education law curtailing Hungarian and other ethnic minorities to be educated in their mother tongue) and an AHF letter to then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and later on a meeting with State Department officials, Matthew Palmer, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, and Ivan S. Weinstein, the Hungary Desk Officer—

were successful in blocking the State Department grant. Most American Hungarians found it insulting that the State Department even considered this initiative.

The reasoning is simple. In the US, out of the ten or so major television channels nine are far-left liberal. Americans would not appreciate it if Hungary or some other country told the US what to do in this regard or tried to fund opposition media.

Hungary might have dodged a bullet, thanks to your work. Hungary’s negative political framing is no novelty. Some say that it has its roots in the beginning of the 20th century. Is this the reason why you are dealing with issues like antisemitism?

In November 2019, we co-hosted a conference, titled The Fate of Rescuers in Dictatorships, which honoured Colonel Ferenc Koszorús, whose military intervention in the summer of 1944 prevented the deportation of close to 300,000 Jews living in Budapest at the time, who were about to be deported to Auschwitz. At the conference we also introduced Dr Zsuzsa Hantó’s latest book, Páncélosokkal az életért – Koszorús Ferenc, a holokauszt hőse (With Tanks for Life – Ferenc Koszorús, a Hero of the Holocaust). The book recounts the history of the 13 Hungarians who worked to save the Jews in 1944 and it was prepared from the materials presented at the above conference. AHF is working on getting it translated into English. This is the type of critical issue advocacy AHF does to set the historical record straight. There are critics who

accuse all Hungarians of having been Nazi collaborators by inaccurately presenting facts and the political situation Hungary faced during WWII.

They refuse to acknowledge any fact, including these acts of heroism, that refutes their efforts to ‘tar brush’ all Hungarians. There is no other country under Nazi occupation which did anything heroic of this magnitude to save Jews. These same critics ignore the vicious forces supporting the Nazis in Norway, France, Spain, Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine and multiple other countries, who committed horrible acts of violence against Jews, but they do not talk or write about them, because they were ultimately ‘on the winning side’. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Hungary was the unofficial ‘capital’ of the Jews living in Europe. The biggest European synagogue is in Budapest: I guess because Hungarians have always been more tolerant than other European countries. Many Jews fled from other countries to Hungary, for example from Romania to survive during the first two years of WWII. There were no death camps in Hungary even during the German Nazi occupation in 1944. We want to translate the book and distribute it to universities and think tanks.

What about Trianon?

Similarly, Trianon must be on our agenda because the neighbouring countries still mistreat Hungarian minorities, and not just from a basic human rights’ perspective, but also in terms of collective rights. Romania has not returned many of the confiscated church, school and other civic Hungarian properties. These battles still need to be fought and it is not easy. In 2020, on the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon, AHF organized an international symposium in Washington DC, which, due to the Covid pandemic, was held as an online event. There were experts and authors attending from the US, UK, and Hungary. AHF was successful in having its statement on Trianon published as a full-page article in the Washington Times.