The House of Terror Museum was opened in Budapest twenty years ago. It was the first museum to present, with new and effective tools, the Nazi and communist dictatorships of the 20th century, and the effects of those oppressive regimes on Hungary and our region.

A brutal tank with its gun above us, seen partially from below, almost splitting apart the dimly lighted enclosed courtyard—the armoured fighting vehicle welcoming visitors of the House of Terror Museum is just as effectively oppressive as it was at the time of the opening of the museum.

The war raging in our eastern neighbourhood makes remembering oppressive regimes even more timely these days—and this is what the House of Terror Museum has been offering to visitors in Budapest for twenty years.

The day when the museum opened in 2002 has remained a memorable moment ever since for both younger and older generations interested in Hungarian and Eastern-European history. A vehement election campaign was in full swing at the time, with a right-wing government and a left-wing opposition pitted against each other, and the prime minister was called Viktor Orbán.

Orbán had become prime minister for the first time in 1998, at the age of thirty-five. Back then, he had to govern against a left wing which was much stronger than today, still packed with the representatives of the communist regime that had collapsed some ten years earlier. These figures managed to retain their power—both formal and informal, political and economic—in the new political era. Many people who used to be part of the oppressive apparatus of the communist regime, including some of the hardliners of the Stalinist 1950s, were still around: masterminds behind show trials, prosecutors and hanging judges, secret service officers, sadistic prison guards, and the rest.

The surviving network of the communist regime continued to be active in several spheres of public life

The regime change in Hungary was one of the softest political transitions of 1989–1990: there was no revolution like in Romania, and there was no clear break with the previous regime – the elite of the new system was never purged of the power figures of the dictatorship. The surviving network of the communist regime continued to be active in several spheres of public life. Neither the first democratic government headed by József Antall, nor the first Orbán cabinet representing a younger generation was able to ensure the required level of organized effort against them.

Presentation of the stifling atmosphere, the mechanism of oppression, and the actual realities of the communist system, in order to keep its memory alive, and to confront perpetrators and their comrades with what they had done, was also missing.

The House of Terror Museum was meant to change this. Mária Schmidt and her team, who dreamt up and have been leading this institution since its opening, created a truly unique museum, which was a novelty in 2002, and is still a novelty today.

The House of Terror is not a museum in the traditional sense—in fact, quite a few museum curators were engaged in debates about it around 2002, and political skirmishes related to it have continued to this day. The House of Terror Museum proudly declares that it is committed to representing a narrative: it wants to recount, for Hungarians who once lived under communism, their children and grandchildren, and visitors from abroad, the havoc wreaked on societies by Nazi and communist terror in the course of the 20th century, and the kind of horrors that had to be suffered under the totalitarian regimes by Hungarians, many of whom became victims of those regimes.

This narrative is presented in an environment of spectacularly effective design based on symbols and strong visual elements. The exhibit is not a collection of items on display behind glass at all, as the entire space of the museum, the rooms evoking various periods and milieus, and even the elevator, serve as integral parts of the same narrative. The House of Terror is a kind of anti-totalitarian Gesamtkunstwerk, which, using the symbols and stylistic elements of totalitarian regimes, distorting or parodying them, creates the environment for conveying the central message.

This building was one of the headquarters of the Hungarian national socialists from the 1930s, and it was turned into a prison during the Nazi occupation

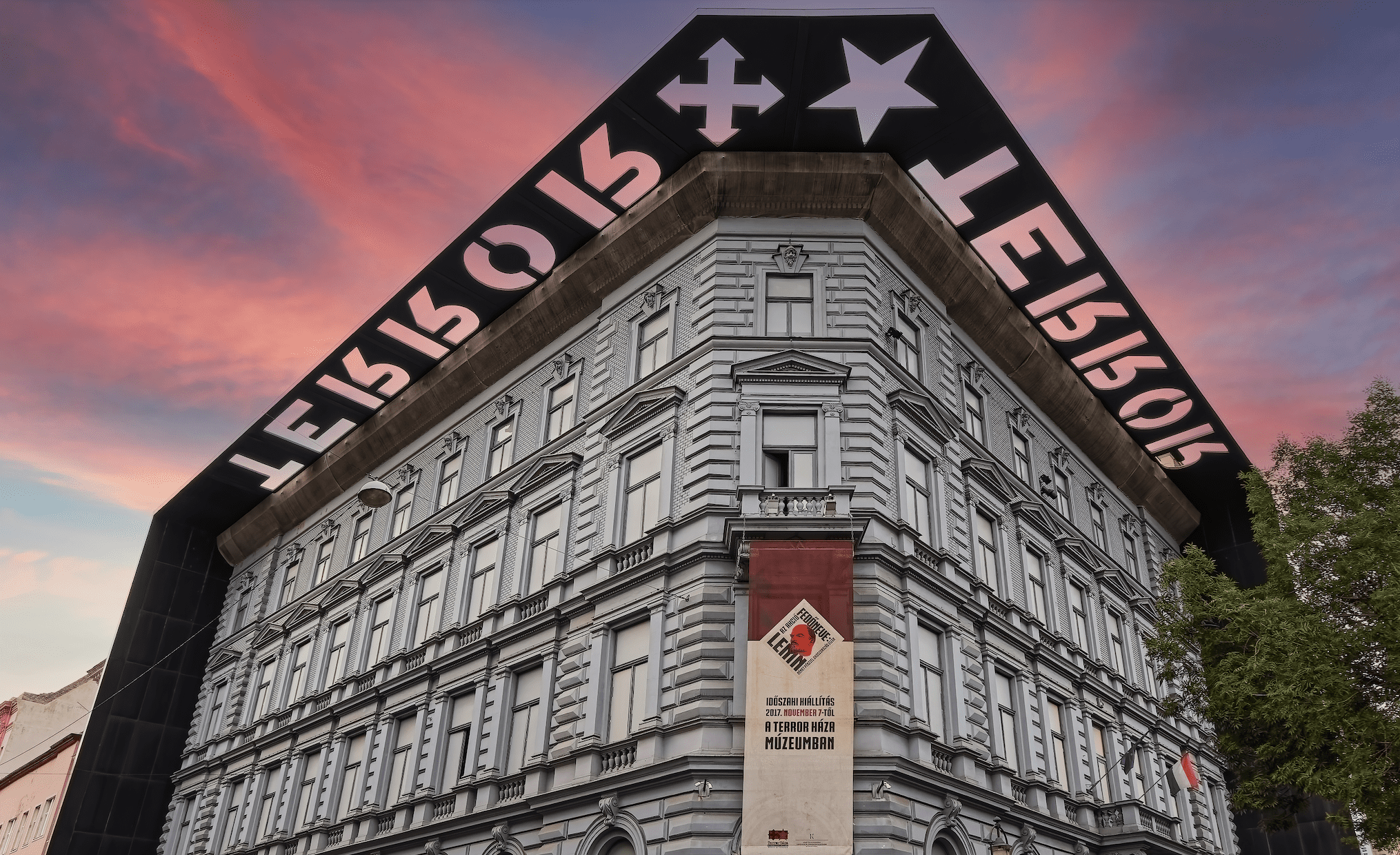

Unlike Hungarians, the majority of foreign visitors are unaware that the House of Terror at 60 Andrássy Avenue is not operating at that address by accident. This building was one of the headquarters of the Hungarian national socialists from the 1930s, and it was turned into a prison during the Nazi occupation between 1944 and 1945, before serving as the headquarters of ÁVH, the dreaded Stalinist secret police of the communists, where the political opponents of the regime were held prisoner and were brutally tortured. The building, which was a crime scene in the darkest periods of Hungarian history, was reborn as a memento of terror at the beginning of the third millennium. It was separated from the neighbouring buildings by blade walls, and it received a depressing greyish blue colouring to evoke the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. The building has been reminding us of the conclusion of that bygone era for two decades now.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary, Prime Minister Viktor declared: ‘This is a success story… it is not former communists any more who say what is good and what is bad, what is true and what is a lie. At last, it is those people’s turn now who were crushed by the regime.”

Director Mária Schmidt said on the 20th anniversary: ‘When we opened the museum in 2002, it was already obvious that historic justice would not be served. We thought it would be necessary to do so in some way, at least, the perpetrators should be displayed on the wall of shame, as a minimum, and our heroes should be presented for everyone to see; we should tell the world about things that happened to us, and we should have a place where people can talk about what they went through, about all the suffering in their families. We just had to have a memorial site, to where people can bring their candles, and this is that place.’

Schmidt then added: ‘The House of Terror Museum has succeeded in celebrating the resistance of the Hungarian nation, and the heroes who gave their lives for the freedom we enjoy today.’