We can hear a lot about the new Museum Quarter in the City Park and the renovation of the Opera House, but we tend to forget about another notable building of the capital, which has been serving Hungarian fine arts for 150 years now. However, the Old Art Gallery at 69 Andrássy Avenue, known today as the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, has also been renovated recently, and the renowned frescoes of Károly Lotz have been restored, too.

‘As far as I’m concerned, I say once and for all that I regard the future of the Hungarian nation as a purely cultural issue, thus I consider the matter of education and public education to be the nation’s most important matters,’ wrote Baron József Eötvös, minister of religion and public education in the Batthyány, and then in the Andrássy government, in his book titled Culture and Education, published in 1876. Thanks also to this principle, in the last third of the 19th century national artistic life in Hungary flourished, and the successive cultural leaders unitedly supported the creation of institutions that could provide a permanent home for art education and art management. As a result, in 1877, the predecessor of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (MKE), the new building of the Hungarian Royal School of Model Drawing and Teacher Training were born on Andrássy Avenue, the jewel and the most representative part of Budapest, and the first, or as it is still commonly referred to, ‘the Old’ Art Gallery was also built on an adjacent parcel. The new buildings came into being following the lobbying of the members of the National Art Society of Hungary, who, until then, in the absence of a permanent exhibition facility, had been presenting their works in private apartments and in temporary and unsuitable locations, only dreaming of permanent annual exhibitions as in the salons of Paris.

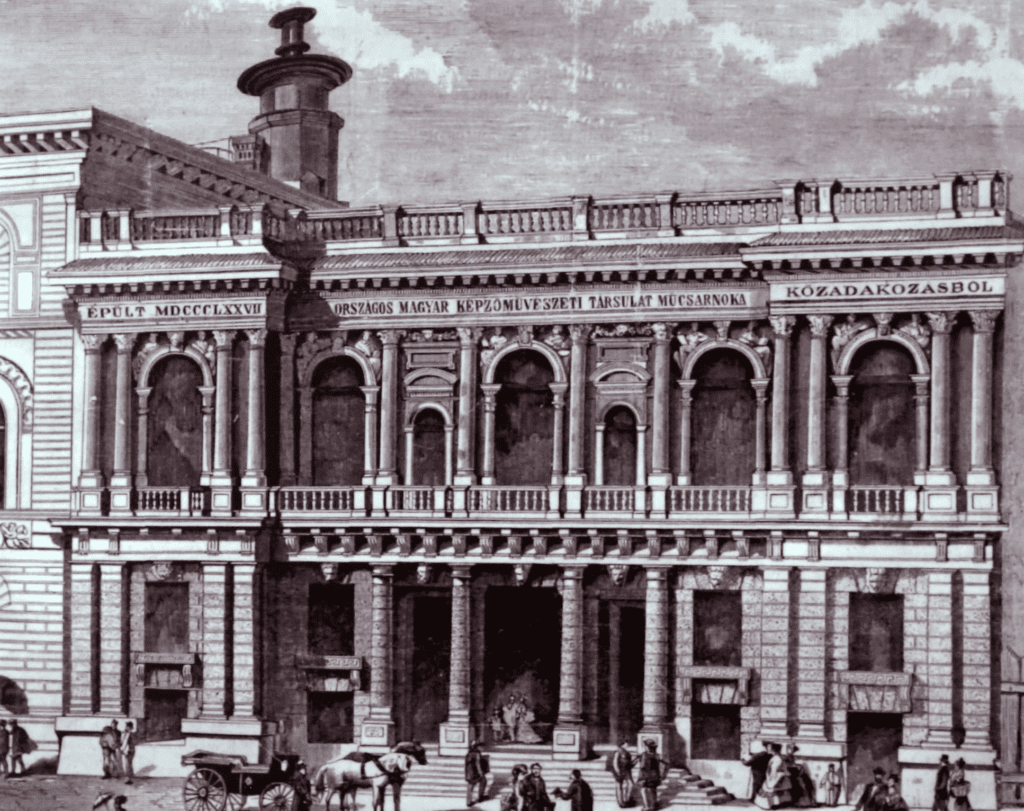

‘The parcel was provided by the capital for a very small sum, and the palace designed in Neo-Renaissance style by Czech-born Adolf Láng and copying the facade of the Palazzo Bevilacqua in Verona, was built from public donations. Count György Majláth, royal justice, headed the committee leading the nationwide fundraising, and the patron of the construction was Crown Prince Rudolf. The largest amount was offered by the royal couple, by Baron Simon Sina, and by Count Pál Esterházy, but in addition to the aristocracy, dignitaries of the Church and numerous private individuals donated smaller or greater amounts too. The names of the 85 most significant donors are preserved on a marble plaque on the first-floor corridor of the building, and an ornate inscription on the facade still proclaims “Built MDCCCLXXVII—Gallery of the National Art Society of Hungary—from public donations,”’ recounted Eszter Lázár, art historian and lecturer at the Department of Fine Art Theory at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (MKE), who was also one of the curators of the highly successful exhibition Térfoglalások, which presented the institution’s history up to World War II.

On 3 November 1877, the National Art Society of Hungary occupied its new home with a representative exhibition, at the opening of which Emperor Franz Joseph personally admired the more than 300 works of 120 Hungarian and 50 foreign painters. But the emperor and the public were not only amazed by the paintings. The interior decoration of the palace was created by the best known masters of the time: the historicist glass windows were made in the workshop of Miksa Róth’s father, Zsigmond Róth; the cast-iron gate of the grand staircase is the work of Gyula Jungfer; and the famous ensembles of murals accompanying the staircase leading to the first floor and those on the ceiling of the grand corridor of the first floor were dreamed up by Károly Lotz, who had already made a name for himself with the interior decoration of Pesti Vigadó and the Hungarian National Museum.

‘Adolf Láng designed the panels accompanying the staircase leading to the first floor and the octagonal pictorial spaces of the corridor of the first floor in such a way that larger figurative compositions could be placed there as well. In the lunettes above the ceiling cornice of the landing, female figures impersonating the various art forms—drawing, copper engraving, art history, applied arts, sculpture, painting, architecture—can be seen on a gold background, and the ceiling of the grand corridor of the first floor is decorated with allegories of fantasy, reality, beauty, and the harmony that suggests the birth of great works,’ said Eszter Lázár, explaining that beside the aesthetic pleasure, we can also interpret these messages from the frescoes. Thanks to the team of restorers led by Dóra Verebes, which included specialised students of the university, the frescoes can shine in their original glory again after their last complete restoration, carried out in 1956. The ‘stirring up’ of the Lotz frescoes was completed after nearly a decade, at the end of 2021, and at the same time the ornate entrance hall, the assembly hall, the staircase, and the rector’s corridor of the Old Art Gallery were renewed as well.

The frequently used term ‘old’ clearly shows that the history of the building, which is celebrating its 100th birthday this year, quickly took surprising turns. Due to the poor division of the spaces, the art society was able to pay for the operating costs and the construction loan (which they had to take out in spite of the generous donations) only by leasing part of the palace, particularly the separate space located on the ground floor. In addition, the seven exhibition rooms upstairs became less and less suitable for their task: due to the rapid accumulation of artworks, the paintings of the regular annual exhibition were at one point hung in four rows, and the larger sculptures were typically exiled to the reception hall on the ground floor. Thus, both the art society and the Museum of Applied Arts, which was also housed in the palace on Andrássy Avenue at that time, were happy to move to the new buildings erected in the construction fever of the Millennium—the former moved to the new Kunsthalle (Műcsarnok) on Heroes’ Square, the latter next to the Grand Boulevard.

The spaces emptied in this way soon gave place to new, less sublime, but all the more popular attractions and forms of entertainment. First, Plasticon, one of the biggest sensations of the National Millennium Exhibition, moved in with 150 realistic wax figures: the figures made by sculptors mostly brought famous public figures and artists to life, including Emperor Franz Joseph and his grandchildren, as well as renowned Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy, rendered while working in his studio. A smaller part of the figures evoked historical scenes, for instance the capture of Francis II Rákóczi. In addition, a lifelike scene depicting a dreadful homicide committed during a robbery was also set up. In 1907, the basement rooms also started to serve as entertainment venues, as the Modern Színház Cabaret of Endre Nagy. later managed by Vilma Medgyaszay, and finally by Artúr Bárdos, opened its doors there. Following several reorganisations, after 1945 the current setup was established: the galleries of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts found a home in the exhibition halls of the palace, and the place of the cabaret in the basement was occupied by the Budapest Puppet Theatre.

‘Of course, the history of the building is far from over. The spaces above the ground floor are used by artists and art students on a daily basis, and their works are presented at the periodic exhibitions of the Barcsay Room. In other words, the past of the Old Art Gallery is the present at the same time,’ says Eszter Lázár. And, of course, that of the general public, too. The purpose of the series of exhibitions and celebrations commemorating the 150th anniversary was also to draw attention to the work being carried out within the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, by presenting the renovated parts of the building and especially the magnificent Lotz frescoes. As a matter of fact, MKE is one of the strongholds of Central European art education. Beside its BA programmes including courses in art conservation and art curatorship which are unique in the region, the university is famous worldwide for its incomparable education in art anatomy.

Click here to read the original article