Sometime in the spring of 1870, in a dusty little town in Western Hungary, the financial security of a young, talented lawyer–and perhaps, he feared, his entire life –was about to fall apart. The little savings he had accumulated so far–not much, since he never accepted money from poor people–seemed to have been completely drained by an unscrupulous business swindler. He had previously conducted an auction, during which a Jewish buyer had given him a false name. The fraud was uncovered, and the auction was cancelled – but the injured creditors sued the young lawyer for a huge sum in damages, which was adjudicated by a court. The case was going to ruin the young lawyer both morally and financially. Finally, at the last moment, the High Court overrode the previous verdict and saved the innocent jurist. However, mental wounds heal slowly, and Győző Istóczy, the subsequent leader of the Antisemitic Party in Hungary, sought revenge.[1]

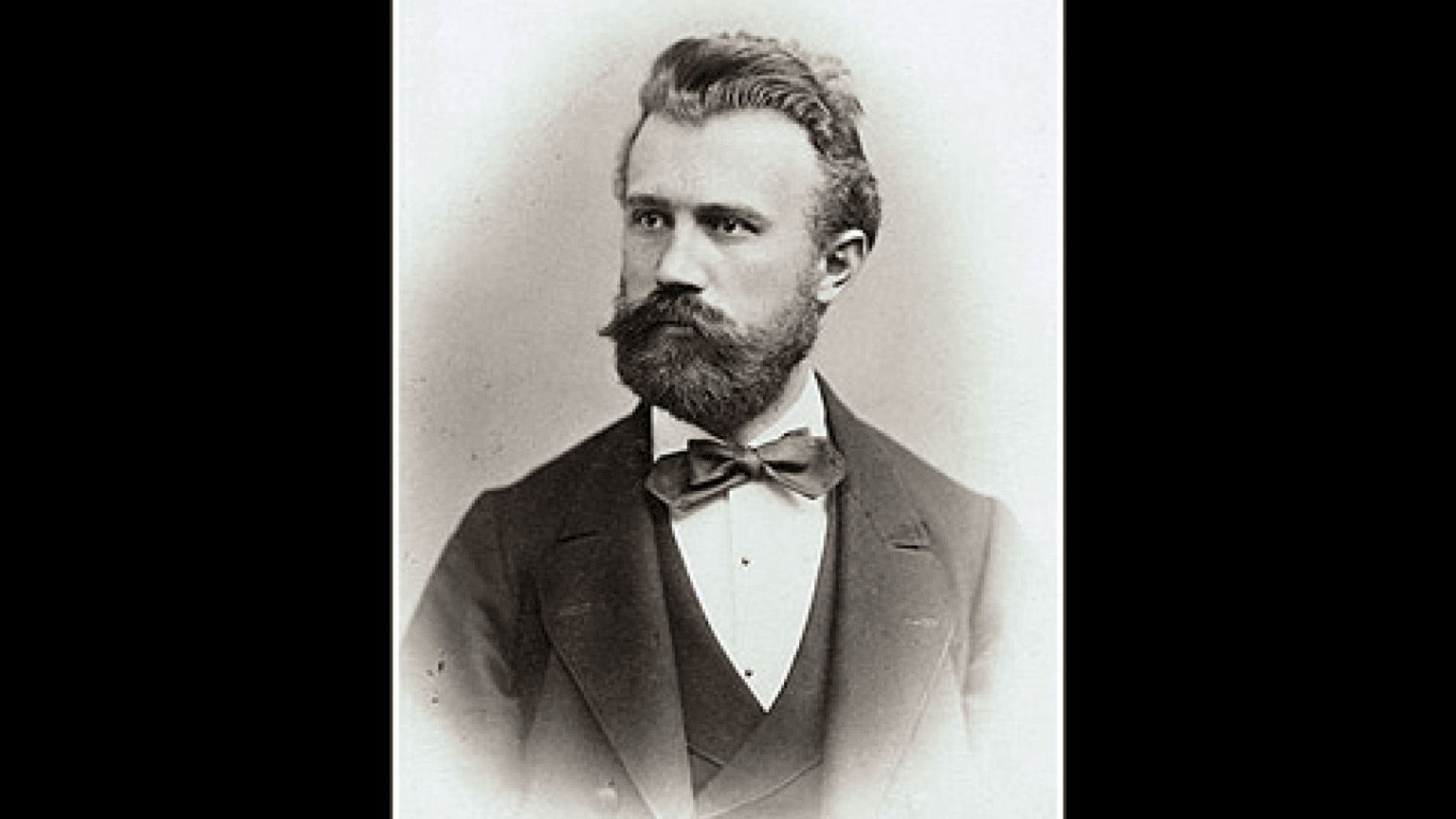

Istóczy came from a downtrodden noble family. As a lawyer, he graduated in the first class where Jewish students were present, and there is no indication that he had anything but a good relationship with them, as we find his name among the supporters of the election of the first Jewish representative of Vas County. He had previously described himself as ‘a liberal friend of the Jews’. However, not much of his philosemitism was left after the above incident (which was perhaps true, perhaps not – we only know the story from the pen of antisemitic writer Zoltán Bosnyák, who had interviewed Istóczy’s relatives). Istóczy himself wrote: ‘I asked myself the question, if I, who had received a higher education and was not entirely dim-witted…and occupied a prestigious social position…was so easily bested by the Jews, well…what is it the Jewry cannot do? A secret world was revealed to me, which showed the cruel minefield of Semitism against the defenceless non-Jewish population in all its harsh reality and enormous dimensions. [This was a fight] in which the non-Jewish population had to inevitably perish. And I decided that I would shout ‘stop’ to Semitism, before it reached a final victory…’ [2]

He had previously described himself as ‘a liberal friend of the Jews’

The “Jewish world conspiracy” behind the Jewish swindler from Baltavár sounds like a bad joke, even though Istóczy was not joking: he became the most decisive and perhaps the only truly famous antisemitic politician of Dualist Hungary. Representing the county of Vas, Istóczy was elected to the Parliament, where he distinguished himself with his anti-Jewish speeches as early as 1875. Istóczy wanted to get rid of “the Jewish danger”, that is, he wanted to erase Jewish life from Hungary as soon as possible.

In 1878, he held a speech in the parliament, with which he truly got himself into history books. Istóczy presented a proposal to the National Assembly for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine as the most obvious way to eliminate the Jewish “threat” and thus preceded most modern Zionist politicians who ever expressed similar views, including Theodor Herzl.[3]

Although there had been proposals for a Jewish state in Europe before, these were discussed only in provincial Hebrew-language periodicals, read only by a few Jewish intellectuals in secluded corners of the world.[4] Whether Istóczy got the idea from a similar source, it is impossible to know. What is certain is that he referred to articles from proto-, i.e. pre-Zionist newspapers in his speech, detailed below – and he put his proposal directly at the time of the conference of the great powers who were meeting in Berlin at the time, so that they would take notice. Of course, his proposal came to nothingat the time, but it is a fact that a novel political idea for the establishment of the later state of Israel was first voiced in the Hungarian Parliament–and from the mouth of a rabid antisemite.

His motion read: ‘The house shall declare…[that] the Jewish people, driven out of their conquered homeland, may at last be served justice by having their much-loved original homeland, Palestine, sufficiently enlarged, as an autonomous province under the sovereignty of the [Turkish] Empire…or as an independent Jewish state. Thus the Jewish people, who in its current [dispersion] is hindering the progress of the European nations and endangering Christian civilization, could return to its origins, with the benefits of its own national government and national institutions…as a vital, powerful new element, the will become an effective factor of civilization.’[5]

According to him, the “Jews” wanted to “enslave” European peoples, and the only defence against such a scheme would be the establishment of a Jewish state. Istóczy claimed that never in the past 1800 years was the international situation so ripe to create a Jewish state as then. Why not do it, he must have thought. His era was the epoch of national awakenings and the rediscovery of ancient heritage all across the globe. Istóczy cited the examples of Hungary, Greece and Italy, and claimed that the Jewish state could be next.[6] According to the parliamentary minutes, his words were met with laughter.

While Istóczy’s speech cannot be compared to benevolent Jewish and non-Jewish calls for a Jewish state–his remarks were clearly antisemitic and his intentions were harmful–the scholar cannot fail to remark that his words showed certain assumptions that were popular among Zionist thinkers as well. Istóczy also seemed to believe that since the dispersion, the Jewish people had “dropped out” from among the peoples that shape history, and that only by returning home could they once again take control of their own historical destiny. Another parallel can be seen between the early Zionist thinkers and Istóczy’s opinion in his citing the example of the European peoples who won their freedom before the Jews. In addition to “what”, the antisemitic representative also answered the question of “how”. In his opinion, in order to regain Palestine, which was part of the Turkish empire before the First World War, the Jews should approach the Turkish sultan: ‘The Turkish empire, which has diminished in strength, lacks and will increasingly lack material…factors. Therefore, it is necessary that…the Jews…with their financial power…implement the regeneration of the Turkish empire in Asia, which is suffering from a chronic need for money.’ Searching for bargains and relations with the Turks were the central goal of Zionist diplomacy until the end of the First World War, as they repeatedly approached the Turks with the offer to fix the empire’s economic woes in exchange for Palestine – the same ideas that Istóczy suggested in his speech.

Istóczy also appealed to the ‘Jewish patriots’ in his remark: he made it clear that he was not talking to ‘Jewish world-citizens’, but to those Jews, who ‘have safeguarded the ancient traditions devotedly for two thousand years”. Istóczy openly called on these Jews to dissimilate from Hungarians: ‘those who feel they are aliens here in Europe, who want to hold on only to their national and racial peculiarities…who do not want to become one with us: our best wishes for their happiness, and may good luck accompany them and keep them safe on their journey to Palestine, from where they were chased away 1800 years ago.’ In a strange move at the end of the speech, he declined to make a motion to vote on his proposal. It is perhaps no surprise that the liberal Ágoston Trefort, Minister for Religious and Public Schooling Affairs, expressed his disappointment over Istóczy’s speech, which he labelled ‘contradictory to the noble traditions of this House’, and of which he voiced his hope that ‘it will fade away forever in this House, without any echoes.’

They even renamed him ‘Zsidóczy’, which was the merging of his family name with the Hungarian word for “Jew”

Well, the speech did reverberate. Borsszem Jankó, a satirical journal edited mostly by Jews, ran a “reader’s letter”, written in a typical Yiddish register, which said: ‘Just because the stable boys are sending us to Jerusalem, we should go to Jerusalem? If the stable boys don’t like us: they should go to Jerusalem!…Therefore I suggest to Istóczy that he to Bethlehem, or else he will end up in Bedlam (a mental asylum – ed.)[7] After the vitriolic piece, Istóczy became a regular target of the journal’s jokes, which often revolved around his supposed Jewish heritage. They even renamed him ‘Zsidóczy’, which was the merging of his family name with the Hungarian word for “Jew”.

Yet Istóczy claimed to have received at least some Jewish support. He stated that in an unspecified year, but after his grand speech, one Jew approached him and said: ‘Last Saturday the news spread in our synagogue that you would visit us…Yes, we have great respect for you, and we would have loved to have you there, as we Orthodox people verily agree with you.’[8] While we only know this story from Istóczy’s own telling, it is a fact that three Zionists submitted Istóczy’s motion in a letter to British PM Benjamin Disraeli and Chancellor Otto von Bismarck at the Great Congress in Berlin in June-July 1878: ‘Like all other peoples of the East, we Jews, poor and oppressed, humbly request that Your Excellencies use their strength and goodwill so that through the intercession of our honourable kings, we may obtain a homeland in the ancient land of our fathers, as a lawful and independent kingdom, in accordance with the attached proposal of Istóczy.’[9]

The antisemitic politician later recalled as a pleasant memory that ‘this motion of mine and my accompanying speech have been so appreciated by the Zionists worldwide that since then, for example, the German Zionist Central Committee based in Berlin…recently asked me for my speech to be included in the history of the Zionist movement.’ [10] Istóczy’ s response (the original request is missing) can be found in the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem, in which he indeed writes that ‘for the sake of the case, it would be beneficial for both parties if this publication of mine received as much recognition as possible in Zionist circles, because that would certainly contribute to the faster development of the healthy, wholesome, modern Zionist movement.’ [11]

The story described above does not mean that there was an inherent connection between antisemitism and early Zionism, it rather reflects upon the fact that different nationalist movements could, independently from each other, strike a similar tone in their criticism of contemporary liberalism – the chief tenets of which were Jewish emancipation, assimilation, and unlimited Jewish immigration. Apparently, the ideal of a restored Jewish state could appeal to both Jews and antisemites in this period – this might seem ironic today, but before the Holocaust, it was not unimaginable for national movements, even so different as the ones above, to find common ground in their critique of liberalism.

[1] Bosnyák Zoltán, Istóczy Győző élete és küzdelmei,, Budapest, Könyv és lapkiadó részvénytársaság, 1940, pp. 22-23.

[2] Istóczy Győző élete, pp. 23-24.

[3] For a discussion of this question see: Andrew Handler, An Early Blueprint for Zionism. Győző Istóczy’s Political Anti-semitism, New York, Columbia University Press, 1989.

[4] Shlomo Avineri, A modern cionizmus kialakulása. A zsidó állam szellemi gyökerei, Budapest, Századvég, 1994, p. 109.

[5] Istóczy Győző, A zsidó állam visszaállítása Palesztinában (24 June 1878), in Istóczy Győző, Istóczy Győző országgyűlési beszédei, indítványai és törvényjavaslatai, 1872-1896’, Budapest, Buschmann F. könyvnyomdája, 1904, pp. 42-64.

[6] For this and the following quotes, including Trefort’s response see: Istóczy Győző országgyűlési beszédei, pp. 42-64.

[7] Borsszem Jankó, 16 June 1878, p. 5.

[8] Istóczy Győző, Emlékiratfélék és egyebek, Budapest, Buschmann F. utódai könyvnyomdája, 1911, p. 23.

[9] Raphael Patai, The Jews of Hungary: History, Culture, Psychology, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1996, pp. 348-349.

[10] Gyurgyák János, A zsidókérdés Magyarországon. Politikai eszmetörténet, Budapest, Osiris, 2011, pp. 315-316.

[11] Central Zionist Archives (Jerusalem), K12/38. Istóczy’s response to an unknown person, 5 Aug. 1906.