József Kőrösy was originally born as József Dávid Heiduschka in Pest on 20 April 1844.[i] His father, Dávid was a merchant in Pest, who later settled in Békés County. At the age of six he lost his mother, Nanette Pollák, and his father sent him to his brother-in-law, Henrik Pollák, a doctor in Budapest.

After graduation, he became a bank clerk, where his hard work and intelligence attracted the attention of his supervisors. He wrote articles for the newspaper Pesti Napló, which attracted the attention of István Gorove, Minister of Trade, who appointed him a member of the National Council of Statistics in 1867, while Baron Zsigmond Kemény entrusted him with the editing of the economic section of Pesti Napló. He changed his name to Kőrösi at the age of 25.

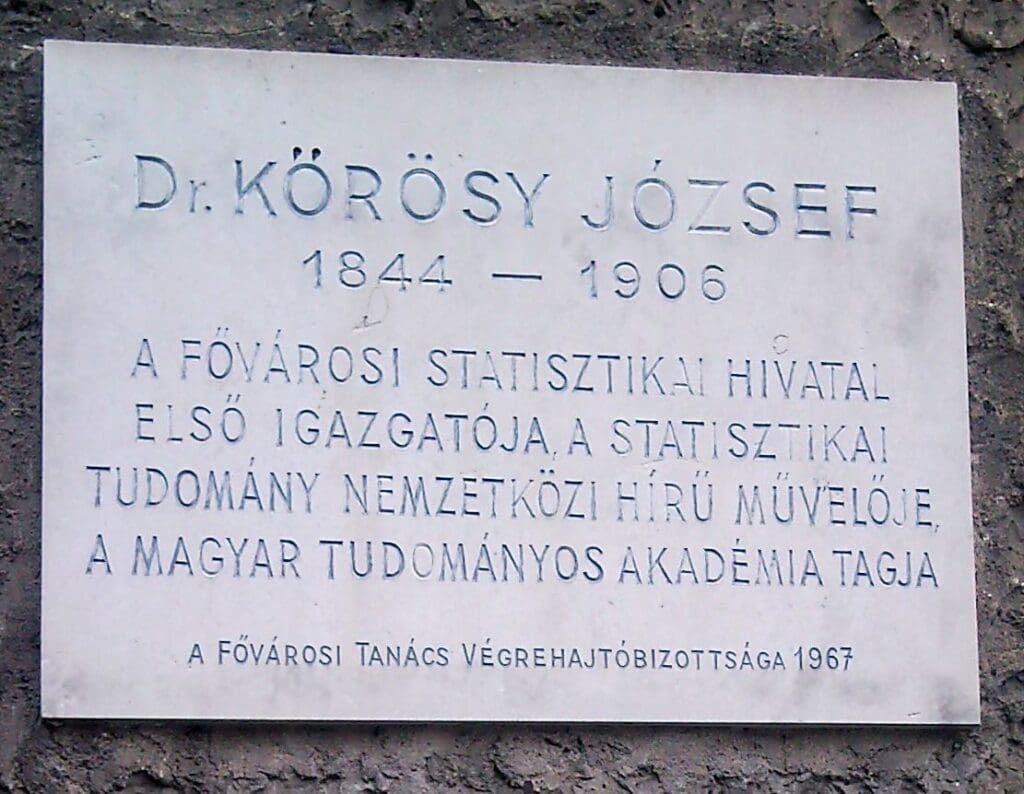

In 1869, the new statistical office of the capital was created, headed by Kőrösy.

He studied the methods used in Vienna and Berlin to conduct the census of the population of the capital. He had little help in his work, aided by only 2–3 assistants on low salaries. In 1873, Pest was united with Buda and Óbuda, which placed an additional burden on Kőrösy. Meanwhile, he did not stop publishing statistics on the capital in German, attending conferences abroad and writing articles for newspapers. His research, honestly describing the social situation of the capital, also led to a conflict with the government.

His persistent work soon bore fruit: in 1873, a delegation of the Vienna Statistical Office came to study his work in Pest—and not vice versa. And The Westminster Review wrote in 1876 that they read with envy the thorough data on Pest, adding they wished there were only such a thing in England!

In the meantime, Kőrösy started to teach statistics in Budapest, the very first person to do so in Hungary. In 1896, he became a doctor of the University of Kolozsvár (today, Cluj in Romania), and was awarded nobility and the title of szántói, as well as the right to spell his name with a ‘y’ (indicating noble ancestry).

The family never converted to Christianity, though, and the Kőrösy coat of arms included two stars of David.

In 1903, he was elected a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He was also inducted into several knightly orders, such as the Order of Franz Joseph, the Russian Order of St Anne, the Belgian Order of Leopold, the Bavarian Order of Michael, and the list goes on.

It is wroth noting that Kőrösy was a fervent Hungarian patriot. In 1898, to give an example, he wrote an alarm-raising essay on the ‘Slavification’ of Northern Hungary (the Upper Lands, today’s Slovakia). He also chose the name Kőrösi after the river flowing near the settlement in Békés County, where he grew up, and the title szántói because his work had led to the discovery of the Slovakisation process of Abaújszántó. At the same time, he made generous donations to Jewish causes as well.

Unfortunately, he developed a heart condition as a result of excessive work, and in his last years he was often forced to take long rests. He finally passed away on 23 June 1906—supposedly the day when he received the letter asking him to retire.

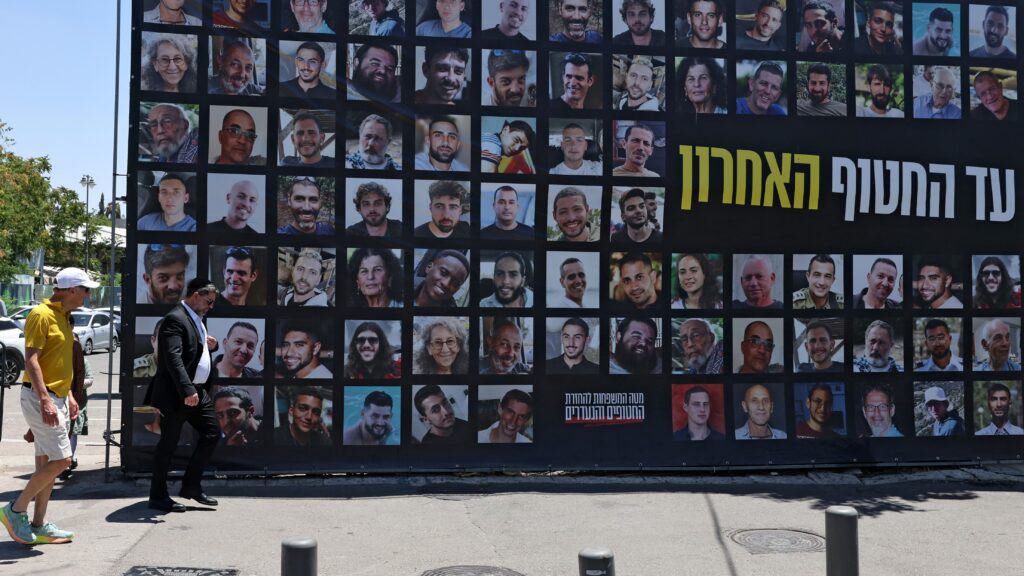

Interestingly, his wife, Gabriella Katzau, a Viennese Jewess, also had Zionist relatives, while his son Kornél became a supporter of Hungarian Zionism. Strangely enough, the family was not pushed towards Zionism by anti-Semitism, at least not in the case of Kornél, while the grandson, while Ferenc did make references to anti-Semitism and the numerus clausus law in his memoirs. Ferenc even made aliyah to Israel, so Kőrösy’s great-grandson Yossi was born there. Thus ended the Hungarian part of the story of a Hungarian Jewish family that received nobility.

[i] This article is based on the following works: Dr. Tivadar Antal Saile, ‘Kőrösy József hatása a statisztika fejlődésére, Értekezések a Filozófiai és Társadalmi Tudományok Köréből, 2/9., 1927 and Ferenc Kőrösy, ‘A Kőrösy család és a vele kapcsolt családok’ In: Sándor Scheiber (ed.), Évkönyv – Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete, 1983–1984, Budapest, 1984.