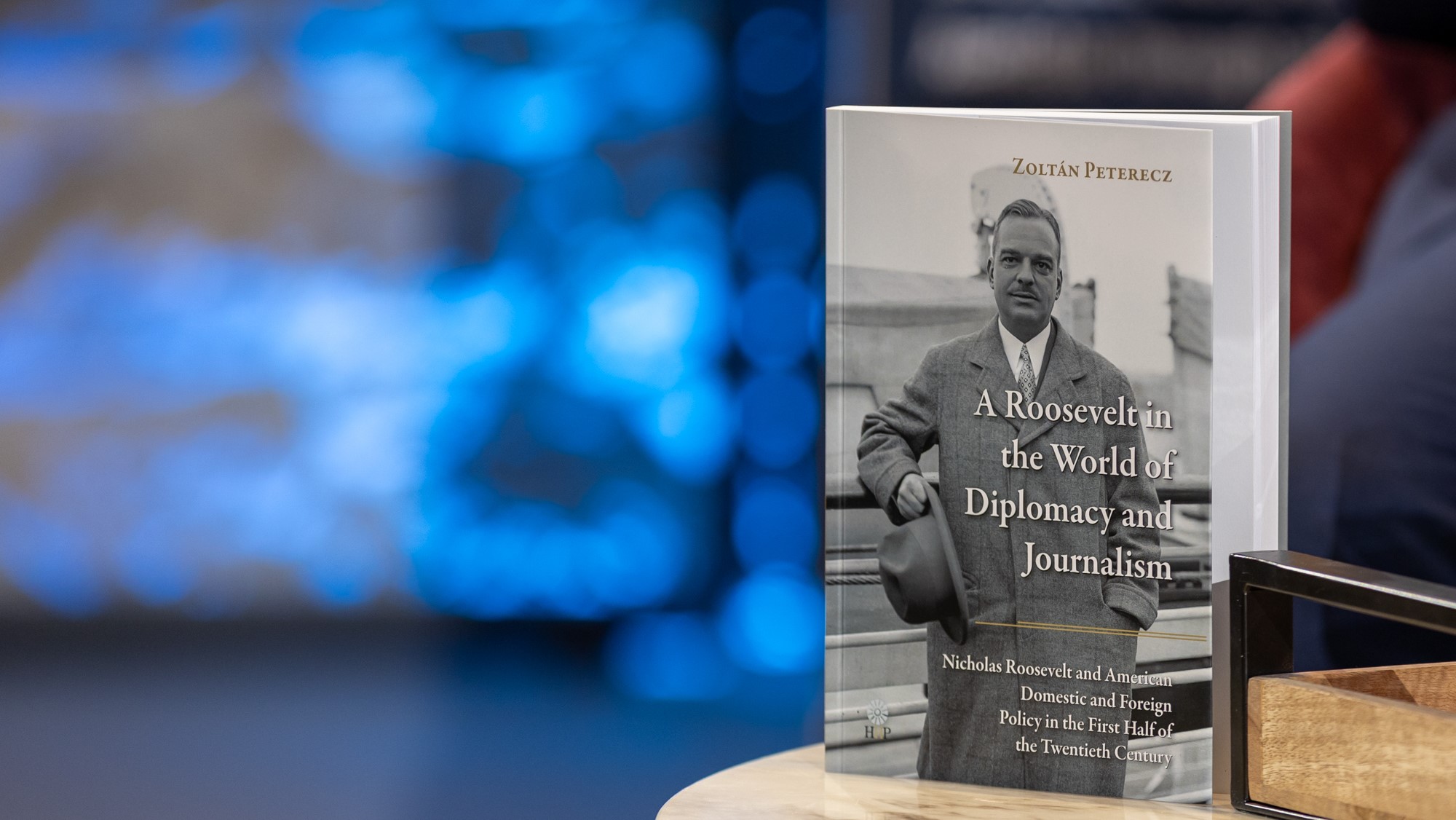

In the refined company of scholars and seasoned minds, the Danube Institute once more played host to a gathering of notable discernment on 29 April 2025. On this occasion, it was the figure of Nicolas Roosevelt (neither president nor titan, yet a witness to much) that summoned the assembly. Presiding over the exchange was John O’Sullivan, who lent the occasion both gravity and wit, while Dr Zoltán Peterecz presented his new biography of Roosevelt: a study both ambitious and delicate, spanning diplomacy, journalism, and the private deliberations of a complex man.

Though not the most illustrious bearer of his name, Nicolas Roosevelt served as US Minister to Hungary and left behind a considerable corpus of writing, from confidential diaries to public memoirs. His was a mind formed by proximity to power, shaped by patrician certitudes and progressive intentions, but often shadowed by condescension and misjudgment. This duality between aspiration and limitation, engagement and aloofness, formed the heart of the conversation.

Two other interlocutors joined Dr Peterecz: Professors Balázs Ablonczy and Tibor Glant, each contributing perspective and scholarly weight. The discussion unfolded not merely as a presentation, but as a portrait in motion: of a man, a milieu, and a method of seeing the world that, though diminished, still casts a long reflection.

The Roosevelt in the Middle

Nicolas Roosevelt entered the world with a name both distinguished and burdensome. Born into the lesser branch of a family that produced two American presidents, he was orphaned young and raised in the formidable household of Theodore Roosevelt himself. This early proximity to greatness endowed him with ambition and a keen political instinct, but also a lifelong awareness of his secondary station. As Dr Zoltán Peterecz noted in his opening remarks, Roosevelt’s life was one of perpetual comparison, sandwiched, in history and in temperament, between men of commanding fame.

‘Born into the lesser branch of a family that produced two American presidents, he was orphaned young’

That he harboured few doubts about his own abilities is beyond question. He regarded his intellect as superior to most and did not conceal his belief that greater recognition was owed to him. His early entrance into public life during the 1912 election set the tone for a career divided between journalism and diplomacy. Though his health and temperament limited his official rise, his prolific pen ensured his continued influence as an observer of events, rather than their architect.

Professor Ablonczy drew attention to Peterecz’s method: a departure from the usual provincial lens often employed by Hungarian historians writing on foreign figures. Rather than anchoring Roosevelt’s biography in Hungarian relevance alone, Peterecz constructs an intellectual portrait with transatlantic breadth, employing rare archival materials from both American and European sources.

The central tension of Roosevelt’s life, as explored by all three panellists, lies in the disjunction between his public and private selves. His public utterances, particularly while stationed in Hungary, were warm and diplomatic; his private diaries, however, revealed judgments often caustic, elitist and dismissive. It is in these contradictions that his interest lies. For Roosevelt was not a hypocrite, but a man shaped by a class that believed itself the natural interpreter of the world, a role he played with imperfect consistency and undeniable flair.

‘His public utterances…were warm and diplomatic; his private diaries, however, revealed judgments’

Diplomatic Sojourn in Hungary

Nicolas Roosevelt’s appointment as United States Minister to Hungary was not the result of a grand strategy, but of circumstance and misstep. As Professor Tibor Glant explained, Roosevelt had previously authored a book on the Philippines that caused such offence that it was publicly burned. The resulting diplomatic embarrassment led to his reassignment to Budapest, a post less controversial yet still significant. Though he lacked formal diplomatic training, Roosevelt adapted swiftly, relying on his linguistic fluency, social confidence and the competence of his embassy staff.

His impressions of Hungary were shaped by both cultural prejudice and a measure of sincere curiosity. To his mind, as recounted by Dr Peterecz, Hungary appeared semi-feudal, populated by a people simultaneously backwards and picturesque. He admired aspects of Hungarian society, including certain strains of high culture, but rarely resisted the urge to portray it through the lens of a superior civilization. This was not unusual for the American diplomatic class of the time, but Roosevelt’s writings gave it particular expression. In private, he likened Hungarian peasants to Russian serfs and echoed the orientalist tropes common in French diplomatic correspondence.

Roosevelt’s attitude toward Hungary’s political class was more nuanced. He held Prime Minister Pál Teleki in high regard, swayed perhaps by the carefully managed information and personal attention Teleki afforded him. His successor, Montgomery, would form different opinions, reflecting the subjectivity of American diplomatic reporting. As Professor Ablonczy noted, such diverging assessments were common among US envoys.

The most revealing documents in Peterecz’s biography may be the unpublished writings included in the appendix. These texts show Roosevelt’s reflections unfiltered by editorial caution. In them, Hungary becomes a stage for Roosevelt’s broader concerns: the future of Europe, the limits of diplomacy and the uneasy task of representing American interests in a region few in Washington truly understood.

The Mind of a Chronicler

Though Nicolas Roosevelt never held the levers of power, his legacy rests in what he recorded. He was, above all, a writer—of memoirs, dispatches and, most revealingly, of diaries. It is in these private documents, as Dr Zoltán Peterecz emphasized, that Roosevelt’s mind is most clearly laid bare. They are candid, acerbic, sometimes offensive and often insightful. His public speeches and later autobiographies, shaped by decorum and the conventions of publication, offer a softened version of the same man.

The tension between these two voices (the polished diplomat and the private chronicler) defines Roosevelt’s historical interest. He could be deeply condescending, particularly toward peoples and cultures outside the Anglo–American sphere. His writings contain remarks that, in today’s context, are unquestionably antisemitic and ethnocentric. Yet, he could also be perceptive, especially on economic and political trends. During his time in Hungary, he sensed the deep instability of the region and grasped the limits of American influence there, however much the Hungarian political class hoped for US support.

The discussion turned to Roosevelt’s social class, that Protestant, Northeastern elite which, while often blind to its own prejudices, laid the institutional foundations of postwar Western security. Roosevelt, however, stood apart from figures like Dean Acheson. He belonged to the same milieu but lacked the strategic vision or political clout of its leading members. As Professor Glant observed, he had the pretensions of greatness without the means to achieve it.

‘He had the pretensions of greatness without the means to achieve it’

In his final decades, Roosevelt withdrew from public life. The early death of his wife, declining health and the passing of his moment left him in quiet frustration. He turned to environmental writing, echoing a strand of Republican progressivism that long predated its modern political associations. The diarist survived the diplomat, and in his pages, the 20th century flickers to life.

Questions and Answers

As the formal discussion gave way to questions from the audience, the exchange took on a more conversational tone, yet retained its scholarly sharpness. The queries were pointed, and the replies thoughtful, each adding dimension to the portrait of Nicolas Roosevelt as both diplomat and diarist.

Adam LeBor opened the Q&A with a thriller writer’s practical curiosity, asking whether Roosevelt had any connection with US intelligence services during the Second World War. Dr Peterecz answered with candour and some regret that he had not. Had Roosevelt engaged with the intelligence community, the book might have taken a more dramatic turn.

A question followed concerning Roosevelt’s relationship, if any, with the Hungarian diaspora that grew after the 1956 Revolution. Again, Peterecz was clear: Roosevelt kept his distance. Though he had once lived in Budapest and written at length about it, he did not involve himself with émigré politics.

Afonso Moura posed a more interpretive question: Did Roosevelt, like many Westerners, view Hungary through a Germanic lens? Peterecz replied that Roosevelt saw Hungary not so much as an extension of German culture but as a semi-feudal society, backwards in structure and charmingly alien in temperament.

Hugo Martin shifted the focus to Hungarian historiography. Tibor Glant took the opportunity to reflect on the advances made since the fall of communism. He praised Peterecz for avoiding the oversimplified periodization that had dominated earlier Hungarian history writing, and for restoring a sense of narrative arc to intellectual biography.

Another question challenged the assumption that diaries offer an unfiltered truth. Peterecz defended them as uniquely honest documents, particularly in Roosevelt’s case, where the private tone often contradicted the public one. Glant added that Roosevelt’s multiple rewritings of his 1919 diary showed an ongoing struggle between narrative and memory.

At this moment, John O’Sullivan welcomed the US chargé d’affaires to Hungary, Robert Palladino. With a smile and a sharp sense of timing, Palladino addressed a remark made earlier in the discussion, where 1950s communist historians had described the United States as ‘a young predator’. ‘I assure you,’ he said, ‘I am not a young predator’—a quip that drew laughter and briefly transformed the room from symposium into salon.

Final remarks were offered by Professors Ablonczy and Glant, the former praising Peterecz’s sociological approach and the latter emphasizing the literary merit of Roosevelt’s prose. Peterecz, in closing, expressed gratitude for the thoughtful questions and for the enduring interest in a figure more complex than celebrated.

Related articles: