In 2018 an interdisciplinary project was accepted by the Hungarian National Research Support Scheme the purpose of which is to analyse the complex historical events of the Mongol conquest of Hungary in 1241. It was an invasion led by Batu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, that was characterized by large-scale and indiscriminate massacres. Of the historical facts taken up was one that continues to perplex historians up to the present days: why did the Mongols all of the sudden decide to leave Hungary in the spring of 1242?

Some theorize that the news of the death of the Mongol Emperor Ögedei Khan in December of 1241 had just reached Batu Khan. He, therefore, decided to withdraw in order to be closer to the homeland in case civil war broke out. Other historians suggest that the Mongol horses had devoured all the available grassland in Hungary, which coerced the Mongols to move on. Yet of the most fascinating chronicles of that time, which drew the attention of notable men like Marco Polo (1254–1324) and Pope Innocent IV (r. 1243–1254),

spoke about the entanglement of Genghis Khan with the legendary Prester John.

This priest-king, of reputable phenomenal wealth and power, who was thought to reign somewhere in the East, galvanized monarchs and explorers throughout the High and Late Middle Ages up to the early Modern period just as the mythical city of El Dorado had done for the Conquistadores.

The twentieth century French historian René Grousset suggests that the Prester John legend may have had its origins in the Kerait clan—one of the five dominant Mongol or Turkic tribal confederations in the Altai-Sayan—which had thousands of its members join the Church of the East shortly after the first millennium.[1] The consensus, however, among medievalists is that the story seems to have originated during the twelfth century when the balance of power favored the Islamic world over Christendom, especially after the latter’s unsuccessful crusades. The narrative of Prester John had the practical effect of reinforcing the religious stamina of the crusaders by holding out the promise that a fabulously rich and mighty oriental king-priest was due to march against Islam from the East in support of his fellow Christians.[2]

This is sustained by the chronicles from 1145; f the Syrian priest Hugh who traveled to Europe to fight in the Fifth Crusade (1217–1221). He describes Prester John ‘as a great Christian king whose empire was located somewhere in India—the idea being that the two great Christian empires, that of John and that of the pope, would come together make war on the Saracens occupying the Holy Land, thus sandwiching the enemy between their two indomitable enemies.’

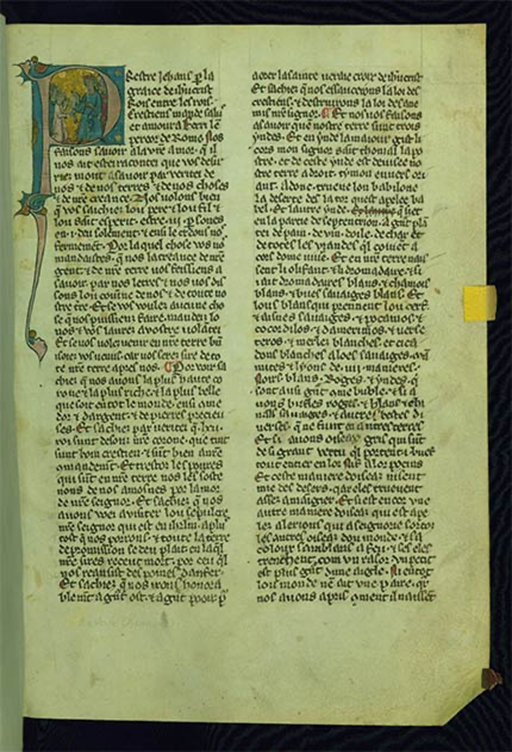

A letter published circa 1165 attributed to Prester John, as recorded by the 13th century monk and chronicler Alberic of Trois-Fontaines, was sent to several Christian rulers, most notably the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180) and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1152–1190). Some had purported Prester John to the Byzantine emperor, who ruled over seventy-two tributary kings and his dominions included the three Indias. In his royal terrains were to be found the Amazons, the Bragmans, and the unclean races of men whom Alexander the Great had walled up in the cities of the north to emerge on the last day.

The inspiration of the letter seems to have been a report spread in the Papal Court in 1145 by the Bishop of Gabala in Syria. He had heard stories of

a certain John, who was both priest and king, and who happened to be a Christian Nestorian

—those who denied the Incarnation of Jesus Christ and represented Him, instead, as a God-inspired man. According to the bishop, Prester John reigned in the distant East beyond Armenia and Persia, and who after overthrowing the Medes and Persians, went onto fight the Muslim incursion in Jerusalem against the Muslims, though was unable to cross the Tigris River had returned to his kingdom.

Although the Letter of Prester John is today generally believed to be a fabrication, the Christians of Medieval Europe were convinced of its authenticity. Pope Alexander III, for instance, sent a reply to Prester John through his physician, Philip, on September 27, 1177— Philip vanishes from history after that, as he probably did not succeed in his mission. Additionally, the Letter of Prester John was a best-seller during the Middle Ages, and over 100 versions of this letter were published in the centuries after its first appearance.

As the years passed and European travelers explored inner Asia and could find nothing but petty Mongol khans with whom to identify the magnificent vision of Prester John, men began to look for him elsewhere.

Part of the endless searches was due to the fact that medieval cartographers had hardly ever ventured to the places they depicted in their maps. ‘The Indies’, for example, was a nebulous term, which could have included numerous places in Europe, from India and central Asia to Africa.

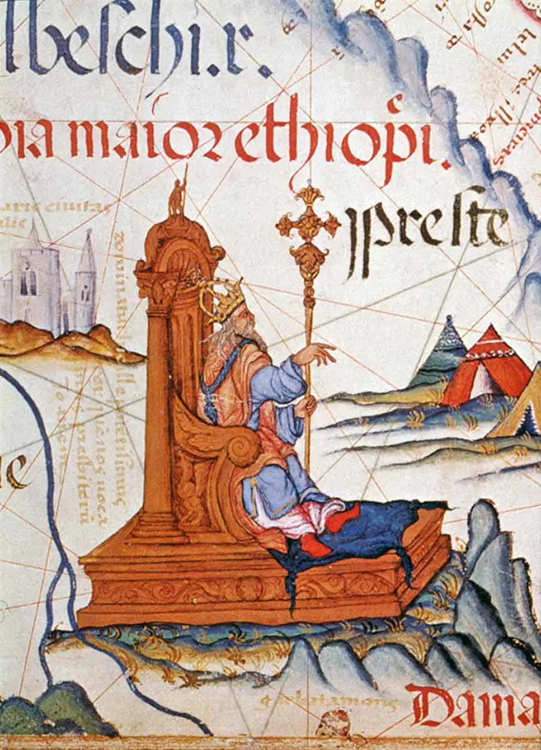

Indeed, by the fourteenth century Prester John was identified with the negus (emperor) Ethiopia. European colonizers and missionaries had held Ethiopia’s status as an isolated Christian empire, surrounded by pagans and Muslims. The notion of Ethiopia as the homeland of Prester John was later asserted by the Portuguese voyages of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The understanding that Prester John’s kingdom was in Ethiopia proved to be the most enduring version of this folkloric figure, so much so that European religious leaders drew links between the Ethiopian Negus and the fabled king. As a result, new accounts of the birth of Christ surfaced, which even casted one of the Magi as having come from Ethiopia.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, the legend of Prester John had lost its appeal in Europe. Rulers and scholars questioned whether he ever existed. Writing in 1684, the German scholar Hiob Ludolf rejected to the idea that Ethiopia was Prester John’s kingdom. His close contact and friend, Abba Gorgoryos, an Ethiopian priest and lexicographer of noble origin, who co-authored with Ludolf encyclopedias in Ethiopian languages of Amharic and Ge’ez probably only lent credence to this belief. The legend of Prester John, without any doubt, is in fact that: a legend. However, his multi-personification that spread into unknown lands for centuries was not only thought-provoking for the people at those times, it bears testimony to a history that merits further study.

[1] René Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes. New Brunswick, Rutgers University, 1970, 191.

[2] Taddesse Tamrat. ‘Ethiopia, the Red Sea and the Horn’, in The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, 179.