Although the religious right is becoming increasingly dominant in Israel, and is a strong factor in the current government, the fundamental Likud worldview is still secular, right-wing Zionism. In order to better understand Israel’s present-day motivations, mode of operation and rhetoric, it is worth worth exploring this worldview in more detail.

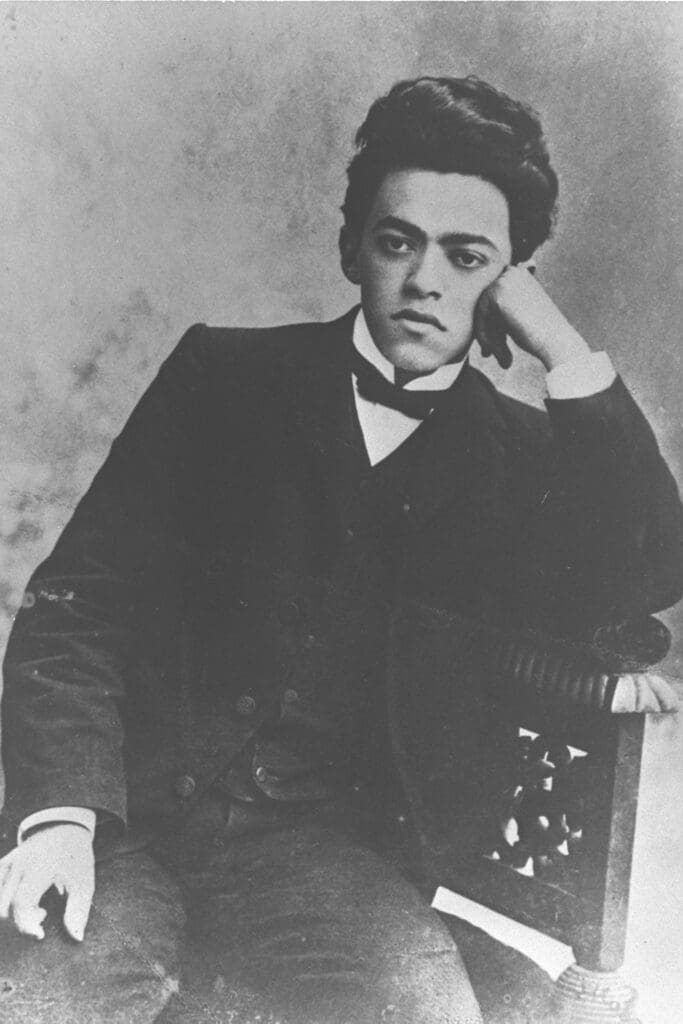

Right-wing Zionism is generally referred to as ‘revisionist Zionism’, where the word revision does not refer to territorial revision but to a revision of the former pro-British policies. Revisionist Zionism was founded in 1925 by Russian Jewish writer, journalist, and politician Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky. Jabotinsky broke with the idea that Zionists should expect the British Empire to hand them a Jewish state, and advocated a programme of establishing a Jewish army and sovereignty. While the relationship with the British is no longer relevant today, Jabotinsky’s militant worldview is still prevailing. One reason for this may be that

Benjamin Netanyahu’s father, the historian Benzion Netanyahu, was Jabotinsky’s personal secretary during his years in New York.

Jabotinsky was an old-fashioned nineteenth-century national liberal and a committed democrat, but it is still a matter of debate whether the same can be said of his supporters. The Zionist writer described his early worldview as ‘liberal anarchy’ in which ‘every individual is [worth as much as] a king’. The free market, freedom of the press, equality for women and respect for minority rights were fundamental tenets of his thinking. But there is good reason why there is an intense historiographical debate concerning Jabotinsky’s views. For as far as right-wing Zionist politicians were concerned, the above-mentioned issues were combined with a militant rhetoric, unrelenting nationalism, and the subordination of the individual to the state—when justified, of course. Jabotinsky proclaimed the absolute necessity of a Jewish state and a Jewish army; he wanted to see the complete emigration of European Jewry and the extension of the Jewish state to its biblical borders.

His opponents often called Jabotinsky ‘Vladimir Hitler,’ and his followers ‘children playing with Jewish swastikas.’ It is also a fact that in 1933 a Nazi newspaper simply described the Jabotinsky-men as ‘the fascists among the Jews today’. If Jabotinsky’s self-definition was true—that his views had always been based on nineteenth-century liberalism and that in this sense he was a political ‘old man’—what was the reason for these accusations? Although he himself made it clear that he ‘did not believe in Jewish fascism’, the labels he was subjected to are put into perspective when we consider what Jabotinsky’s views on authoritarianism and the use of violence were, when he spoke on subjects other than fascism.

Jabotinsky himself described fascism as a ‘cult of discipline’, but he also described his youth organisation—which he named the B’rith Trumpeldor, or Trumpeldor League, after his comrade Yosef Trumpeldor, who had died fighting the Arabs—as an entity acting on a single ‘central command, in a single moment’ and ‘proudly’ becoming ‘a machine, yes, a machine’. When accused of being a militant, Jabotinsky replied: ‘Latin words cannot hold us back.’

The official uniform of the Revisionists was the brown shirt: the colour was supposed to represent the shades of earth, but when the Jewish papers were full of Nazis in brown shirts, the reader of the time could see little difference between the two—a fact that was readily highlighted in the left-wing Zionist press. But Jabotinsky thought uniformity was important:

‘By means of a simple trick, even the worst assimilationist can be carried away, at least for a moment, by the Jewish national enthusiasm: take a few hundred Jewish youths, dress them in uniform and parade them before his eyes—in a regular procession, in which every step of these two hundred kids sounds like thunder—as if he were looking at a machine. There is nothing in the world so impressive as the ability of the human mass to feel and act at certain moments as a single being, imbued with a single will, in a single rhythm. This is what distinguishes the multitude, the mob, and the nation.’

His most detailed reference to his relationship with the Arabs was in his 1923 essay called ‘The Iron Wall’. In it, Jabotinsky argued that the Palestinian Arabs would not agree to a Jewish majority in Palestine and that ‘Zionist colonialism must either be stopped or continued independently of the indigenous peoples’. (The word colonialism was sometimes used by the Zionists, but of course not to refer to an activity such as that of the Dutch East India Company, since they were not seeking to exploit a land for the economic interests of a distant country, but to establish a Jewish state on the former land of their ancestors). For Jabotinsky, this meant that the building of the Jewish state can only continue and develop under the protection of a power that is independent of the indigenous population and the Jewish state can only exist behind an iron wall that ‘the indigenous population cannot break through’.

The only way to achieve peace and a Jewish state on the land of Israel, he argued, would be for Jews to first establish a strong Jewish state, which would eventually lead the Arabs to ‘drop their extremist leaders whose slogan is “never” and hand over leadership to moderate groups who will come to us with the proposal that we both agree to mutual concessions.’

Jabotinsky thus held a complex view: he emphasised the value of the individual over the state, but he considered the nation to be even more important than the individual. And the twists and turns of his practical politics can also be traced back to his stateless statesmanship: although he was critical of the excesses of the monster state, he needed a state—a Jewish state. His followers themselves often described Jabotinsky in simplistic terms, for example by portraying him as a ‘Jewish Mussolini’ in their Palestinian Hebrew newspaper. Their leader sought to check their extremist sympathies, with varying degrees of success.

But Jabotinsky’s influence has not been limited to right-wing Zionism.

Today, he is one of the most important and most widely quoted political thinkers in Israel

—this is obvious if we consider the number of parties that seek to represent his legacy, and perhaps even more tellingly, the many streets that bear his name. The pervasive presence of Jabotinsky in Israeli collective consciousness is very well illustrated by an Israeli news portal not long ago referring to him—erroneously—as the founder of Likud.

Since 2005, Israel has had a Memorial Day to honour Jabotinsky (Tammuz 29, the day of his death on 4 August 1940, according to the Hebrew calendar). At a 2017 celebration, Netanyahu said: ‘I have Jabotinsky’s works on my shelf, and I read them often.’ He also highlighted that he keeps the Zionist leader’s sword in his office. The Israeli Prime Minister reminded that the essence of Jabotinsky’s philosophy was national self-defence and the strengthening of Jewish culture.

The values that Netanyahu believes in and that guide him in this current war are largely inspired by Jabotinsky—and this may explain why his responses to Palestinian terrorism show a strong nationalist, militant streak and why his worldview has little to do with today’s liberalism.