Sovereignty is debatable. If someone seeks a straightforward definition, they will quickly become entangled in the complex web of power dynamics at interpersonal, intercommunal, and international levels, discovering how no individual or entity is really his or her own master.

Yet sovereignty is still craved by everyone, if in different forms. In Central Europe, this sovereignty is very much tied to the longing for the self-government of the centralized state, which is supposed to rule over a homogenous national entity. This yearning has been strongly influenced by the lack of sovereignty over the last centuries. Almost all small- and medium-sized nation-states between the Elbe and the Don experienced conquest, colonization, and imperial takeover in some combination. For these states, the ‘bright future’ meant the eventual liberation of their national centres.

Hungary is no exception among these states. The question of sovereignty is even addressed by the Constitution itself. The Fundamental Law of 2011 defines 2 May 1990 as the reinstatement of the sovereign status of Hungary, which was broken by the German occupation on 19 March 1944 and continued by the Soviets when they soon invaded and, in turn, Sovietized the country. This is the first day of the session of the newly elected and, for the first time in so many years, democratically elected Legislative Assembly of Hungary, which was made up of 386 people.

This means that the start of the democratic legislative work was chosen as day zero. It could have been the formation of the new government a couple of days later, or the end of the drawdown of the Soviet troops stationed in Hungary. In a way, it could have been the declaration of the Hungarian Republic on 23 October 1989.

The first day of the democratic Legislative Assembly is still significant because it means sovereignty in a positive and symbolic sense. The government was logically created after, with a broad coalition of the centre-right MDF and the liberal SZDSZ. But the first day, 2 May, was a day of ‘return’ of democratic forces of every hue to the halls of power. All was symbolic, but it was important.

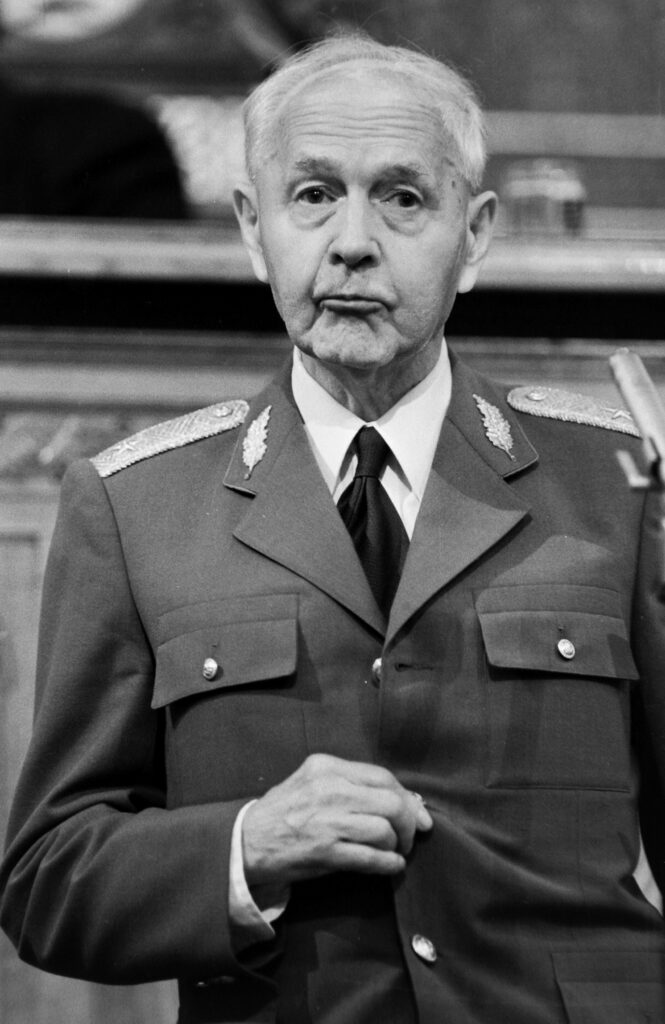

Discontinuities caused by the Communist rule were remedied. Symbolically, the last democratically elected chairman of the pre-communist Assembly, Béla Varga, delivered the speech at the start of the opening session. The intro for the session broadcast on television was full of references to the first elected civic Assembly from 1848. The Father of the House, Kálmán Kéri, presided over the session, who was born at the very start of the century and thus lived through all the crises that hit Hungary.

Historic wrongs were made right, and the fabric of history was fixed. Among the first laws promulgated was a law about the recognition of the contribution of the Revolution of 1956 to Hungary’s democratic development. The Communists denied the Revolution almost until the end, and finally, the revolution’s heroic status became the law of the land. Communists were not paying proper attention to the Hungarian minorities living in neighbouring countries; on that day, representatives of these communities were invited and were sitting in the Parliament of all Hungarians.

The new geopolitical map was laid out as well. The Assembly accepted a commitment to enter the Council of Europe, while Otto von Habsburg, a member of the European Parliament and grandson of the last Hungarian king, looked from the benches. It was made clear that the newly sovereign Hungary belongs to the common European home, where the borders can be made virtual and the fruits of economic development can be enjoyed.

There were a couple of dark clouds over the horizon. One of the representatives of Hungarian minorities, the Transylvanian András Sütő, could not attend despite his invitation. He was lying in a Budapest hospital, where he was quickly flown in after he, among others, was severely beaten in the anti-Hungarian pogrom and riot of Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș) on 22 March 1990. The post-Soviet era showed that it was far from perfect. Ethnic tensions would continue and occasionally escalate across Central and Eastern Europe, and Hungary also felt the shadow of it on this special day.

Other unsettling features were also noted within the interior. As the first Legislative Assembly elections approached, Hungary, awakening from a state where public politics was forbidden for decades, was somewhat appalled to rediscover the cutthroat nature of party politics. On the same day when the Assembly convened, the well-known daily Magyar Nemzet was carrying an op-ed, lamenting the ugly nature of this party’s struggles, while praising the arrival of the democratic age. However, utopias do not exist, and Central European history did not end with the happy start of the new sovereign age of Hungary on 2 May 1990. The roughness of daily politics and the local and global tensions of the post-Soviet age have just intensified since then. Still, Hungary and its elected representatives have the power to at least reasonably independently decide upon what course this small ‘ferry country’ would take. ‘Let the simple working days come now,’ declared Mátyás Szűrös to the assembly in his opening speech. This was success in itself: getting history and politics back on their ordinary track. 2 May, though not a holiday, is a date whose inclusion in the Fundamental Law can be said to be a matter of consensus, because sovereignty is a prerequisite for any kind of ordinary track for a nation, and a backbone of any kind of ordinary democracy. And getting that prerequisite is a huge and lasting achievement that every conscious citizen of this newly democratic country still cherishes and wants to guard.

Related articles: