Today is the 80th anniversary of the establishment of Jewish ghettos in Hungary, marked as National Holocaust Memorial Day. Here we recall the life of an almost completely forgotten figure of Jewish history, the Chief Rabbi of Devecser, Gábor Deutsch.

Gábor Deutsch was born in Karcag, Hungary in 1909. He completed his studies in Kecskemét and at the Rabbinical College in Budapest. As a newly ordained rabbi, he became Chief Rabbi of the community of Devecser in Veszprém county. In 1941, the community had 203 members (4.6 percent of the population).[1] In addition to leading his community, Deutsch published several studies, speeches and reviews, mainly in the Magyar Zsidó Szemle (Hungarian Jewish Review). In addition to this, he was a field chaplain of the Hungarian army at the time.

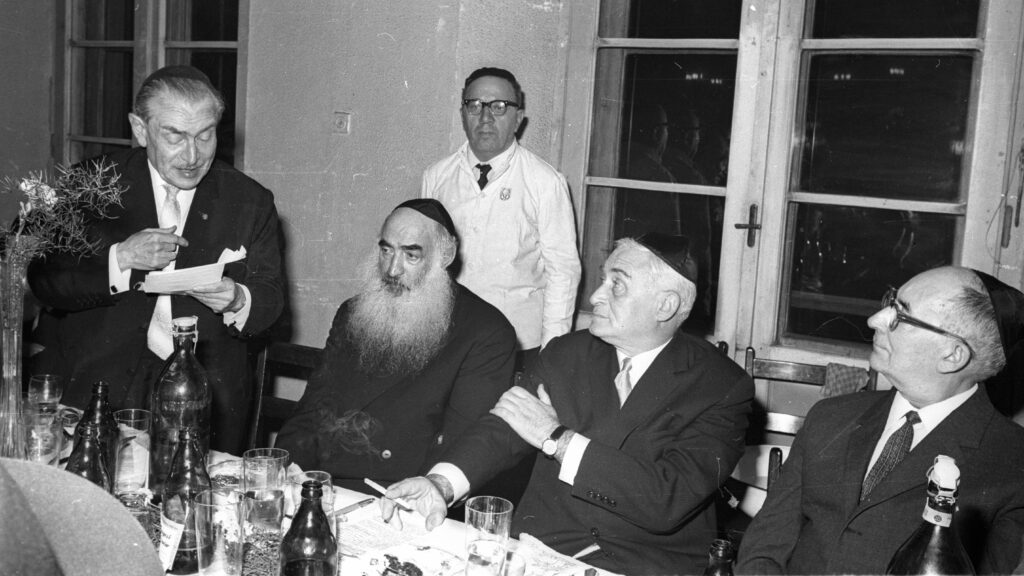

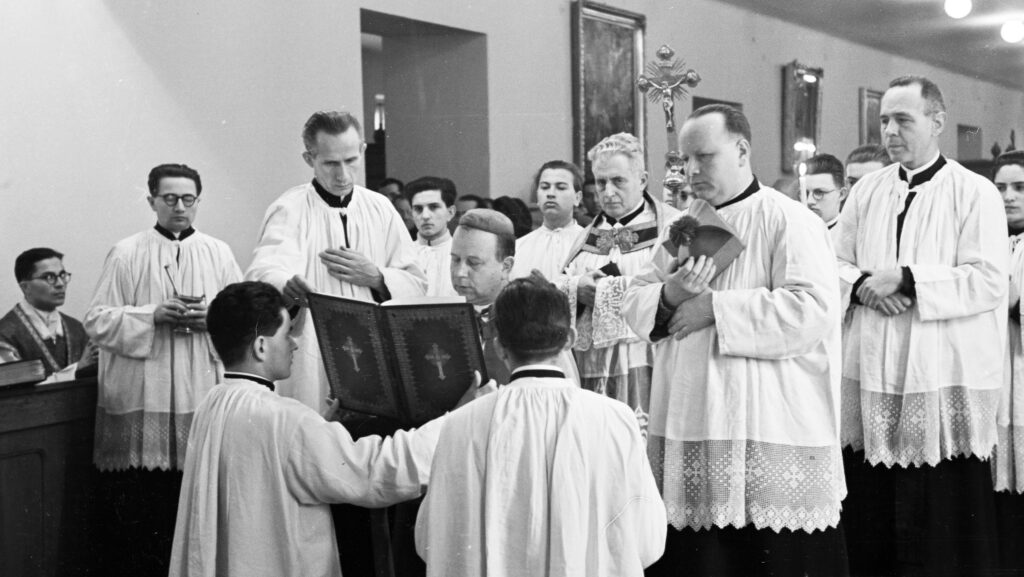

He was also apparently on good terms with the Christian communities in the area, and when the Reformed pastor Kálmán Varga was installed in the nearby town of Ajka in April 1937, Deutsch also gave a speech alongside representatives of the various local Christian denominations. In 1938, when Herman Mautner, the director of a local bank and president of the Devecser congregation, was buried, not only Deutsch gave a funeral speech, but also the local parish priest and the chief notary.

Devecser was a loudly pro-Hungarian orator and commemorated the tragic Treaty of Trianon at least on one occasion. Yet, in addition to his patriotic rhetoric, he was apparently familiar with and appreciated the writings of Zionist authors such as Martin Buber, Yakov Klatskin and Nachum Sokolov, and supported the teaching of Hebrew among young people. Meanwhile, in a 1940 letter, he also welcomed the Jewish scout movement, especially its values of religious education.

The most interesting aspect of his work, however, was undoubtedly his campaign against communism (or bolshevism, in his use of words). He

drew parallels between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in one of his speeches made in 1936:

‘In the East of Europe, a devastating campaign is being waged against all positive religions, especially Judaism; in the cultivated Northwest, in the leading state of culture and civilization, the foundations are being laid for a third empire of intolerance, and in the face of all these attacks, Judaism is increasingly defenceless.’

Meanwhile, he also scourged the age of materialism and ‘moral retrogression’: ‘In these days of the most terrible moral decline, it is incumbent upon us Jews, a people dedicated to the search for God, to give humanity, even in the midst of our sufferings and humiliations, once again the gift of lasting values, the greatest treasures of faith and morality, to continue to proclaim, faithfully holding fast to our ideals, the triumph of the spirit over matter, of idealism over materialism.’

The most thorough summary of his views was his study on Judaism and Bolshevism published in 1937.[2] In his introduction, the rabbi did not deny that he wrote the booklet because many people argued that the doctrines of communism ‘fall on fertile ground among the members of our denomination’, and therefore ‘we consider it timely to prove, point by point, that the classical revelations of the Jewish religious ethos, the Scriptures and the Talmud are opposed sharply to the basic doctrines of Bolshevism’.

According to Deutsch, the ‘historical materialism that underlies Bolshevism is separated by an unbridgeable gap from the profound idealism that pervades the whole of biblical and rabbinic literature’. While ‘Judaism established a direct, intimate relationship between creature and Creator, Bolshevism, on the other hand, substituted the absolute divine power with the elevation of the Party, so that the individual man is not in a dependent relationship with the Supreme Being but with the all-powerful party organisation’.

The rabbi’s writing condemned the totalitarian movements’ pursuit of full control,

which consumes the individual and independent thought. ‘The man who has an independent moral responsibility cannot be condemned to sink into the machinery of the state, because the state, which rests on the individual man, cannot become an end in itself.’ He criticized the Soviet Union’s well-known economic policy based on nationalisation as taking away the individual’s incentive to work for his own well-being. Moreover, he considered forced state socialisation immoral: ‘Better a little with justice than an abundance without justice,’ he quoted the Book of Proverbs.

But Deutsch also criticised the ‘excesses of capitalism’. As he argued, ‘it is sufficient to refer to the economic measures of the Torah, which serve as a strong bulwark against the excesses of capitalism’. ‘At the end of seven years, make a remission. This is the way of remission: let every creditor forgive the debt he has lent to his neighbour’ (Leviticus V. 15 f. v. 1–2).

Deutsch’s conclusion is clear: ‘The biblical and traditional literature still expresses in many places the view that the acquisition of property and wealth is not an end in itself…The biblical state…has the task of bridging the wealth gap, not by force, but in a spirit of love for one’s neighbour. Among all nations there have always been privileged social classes. Bolshevism, in fighting against the present economic and social order, instead of abolishing class distinctions, is in fact striving for new privileges and is preparing once again for the imperialist domination of a single class, the proletariat, which lives by manual labour.’

None of this, of course, saved Deutsch from the deportations of 1944: atheists and religious, communists and capitalists, Zionists and anti-Zionists were all put on the train. The ghettoization of Devecser took place between 24 and 31 May 1944, before the inhabitants were taken to the ghetto in Pápa and finally transported to Auschwitz on 4 July. About forty deportees from Devecser survived the Holocaust, but the Chief Rabbi was not among them. His name is on the memorial wall of the local victims of the Shoah.

On National Holocaust Memorial Day let us also remember this forgotten martyr of Hungarian and Jewish history.

[1] Anna Gergely, ‘Devecser’, In: A magyarországi holokauszt földrajzi enciklopédiája, II. vol, Randolph L. Braham (ed.), Park, Budapest, 2007. pp. 1294–1296.

[2] Gábor Deutsch, Zsidóság és bolsevizmus: világnézeti tanulmány, Székesfehérvár, 1937.