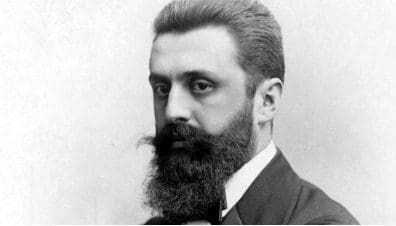

An important source publication was published by the Foundation for the Research of Central and Eastern European History and Society (Közép- és Kelet-Európai Történelem és Társadalom Kutatásáért Alapítvány), which was an old debt of Hungarian historiography: the diary of Herzl Tivadar, the Budapest-born dreamer of Israel, was published in Hungarian – both in print and online.

The original German text was translated by Péter Mesés and János Betlen, the editor was historian Dorottya Baczoni, and the proofreaders were historians Mária Schmidt – director of the Terror Háza Múzeum – and András Gerő. The expert team has done a thorough job with the text, which opens with a 60-page introductory study.

An early American researcher of the document noted that the self-revealing nature of his diary undoubtedly gives a correct picture of the ‘legendary Herzl’. It shows not only what he did, but also who he really was.[1]

Herzl was born in 1860 into an assimilated, secular Budapest Jewish family. Of course, secular is a tactful term, since he viewed religion with a certain amount of ignorance and even hostility. At one point, he even played with the idea of the baptism of the Jews, their ‘immersion’ in the ‘sea of peoples’ with an assimilationist fervour.[2] According to his diary, he set up a Christmas tree without any second thoughts in the presence of the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Güdemann, and he consistently referred to the rabbi as ‘bishop’.[3]

His political Zionism was not at all rooted in the tradition of the Jewish religion, but rather in disappointment over antisemitism

His political Zionism was not at all rooted in the tradition of the Jewish religion, but rather in disappointment over antisemitism – and liberalism’s inability to overcome all social tensions – and this is also highlighted in the recently published diary. Despite all of Herzl’s achievements as a journalist, he wanted to be a playwright, and since his plays did not achieve the desired success, and his personal life was also in crisis, the sensitive and depression-prone man gave way to chasing political dreams. Although some cite the Dreyfus Affair as the cause of the great change, according to Israeli historian Shlomo Avineri, the Dreyfus Affair was not the decisive motive for Herzl’s path to Zionism.[4]

In the very first entry in his political (Zionist) diary, Herzl attributed his concern with the “Jewish question” to his unhappiness and personal troubles. This was very honest, as he admitted that he was projecting his individual failure of assimilation onto society – although there is obviously no need to argue that in hindsight, in the awareness of 1944 and 1948 (the Holocaust and the proclamation of Israel), Herzl was objectively speaking, right. Herzl also refers to his experiences in France in his diary, as he wrote that he came into a “freer” contact with antisemitism in Paris. One of his acquaintances there, the French writer Alphonse Daudet, directly suggested that Herzl should write down his thoughts on the Jewish question in the form of a novel. (And Daudet himself was not exactly a philosemite). Researcher Amos Kiewe considered this to be one of the most important motivations behind Herzl’s writing of his great book, The Jewish State.[5]

After several days of isolated writing – during which Herzl, perhaps ironically, listened to Wagner’s Tannhäuser – Herzl began the preface to his 1896 volume as follows: ‘This is not a lovable utopia… On the other hand, the project before us is based on the application of the driving force that exists in reality. Aware of my weakness, I only mark the machine to be built, trusting that there will be better mechanics than me for the job. It depends on the driving force. And what is this power? The Jewish misery.’[6]

Herzl named antisemitic persecution (‘Jewish misery’) as the driving force of his movement, and as he explained in his diary, that is precisely why he did not want to fight against antisemitism: because one cannot get anywhere with mere arguments.[7]

Interestingly, Herzl treated the existence of the “Jewish question” as a basic fact: ‘The Jewish question exists. It would be foolish to deny this. The Jewish question exists everywhere where Jews live in large numbers. Wherever it does not, the immigrant Jews drag it with them… because of our appearance, the persecution appears. This is true, it must remain true everywhere, even in highly developed countries – France is an example – until the Jewish question is politically resolved.’[8]

He wrote the above lines in his book, but only noted in his diary that ‘the antisemites are right – if we leave it to them (we Jews – ed.), then we can be happy too. It will be proven that they are right (i.e. the antisemites – ed.)’.[9] Obviously, this should not be taken to mean that Herzl stood up for the pogroms, but if we interpret antisemitism as a kind of rebellion against contemporary liberalism, and assimilation as one of the main achievements of liberalism at the turn of the century, then Herzl’s critique of liberalism by definition assumes certain common ground with the antisemites – even if, after the shared “diagnosis” (in Chaim Weizmann’s words), the proposed “therapy” was completely different.[10]

Is it any wonder, then, that the liberal Jewish public life of the time received Herzl with resentment? While the French Jews declared themselves French and the Hungarian Jews Hungarian, Herzl professed: ‘we are a people, one people.’ Aware of this, he asked the question: ‘Will they not say that you are supplying arms to the anti-Semites? Why? Because I admit the truth? Because I don’t claim that there are only excellent people among us’ Herzl wanted to respond to the accusations in advance, clarifying that he alone could not stop the process of assimilation. ‘Whole branches may die, may fall from the tree of Judaism, but the tree lives,’ said Herzl.[11]

‘We are a people, one people’

The Hungarian-Jewish reaction, considering the patriotic spirit of the Hungarian Jews, could be predicted. The editor of the liberal Jewish paper Egyenlőség, Miksa Szabolcsi, responded to the work in a front-page article with the title We do not ask for a new country. At the beginning of his article, he emphasized that such “unhappy memories” of crazy ideas came up most recently during the “unfortunate [Tiszaeszlár] affair” (when in 1882-1883 Jews of the village of Tiszaeszlár were accused of ritual murder – the Jews were acquitted). He continued: ‘Antisemitism is the fog that not only blinds its adherents, but also deprives some of those against whom it is directed of their sanity. This fog gave birth to Zionism, which proclaims Jewish nationality… and also gave birth to the latest book on the establishment of the Jewish state. If the fog will pass … the author himself will laugh at the audacity of his imagination.’[12]

The response to Zionism among liberal Jews was ‘predictable’, writes Canadian historian Yakov Rabkin. “The reaction to Zionism among the emancipated Jews of Central and Western Europe was predictable. Western Jews easily grasped to what extent the theories of the Zionists played into the hands of their world’s enemies.”[13]

Herzl was a national visionary, but in a sense he was also a strongly anti-liberal thinker and thus, it is the task of today’s Hungarian public life to further acquaint itself with him. The new Hungarian book is an important work that deserves a place on the shelf of every interested reader.

[1] J. Hodess, The Real Herzl. An Appreciation of the Man as He is Revealed in His Diaries. In: Meyer Wolfe Weisgal (ed), Theodor Herzl: A Memorial, New York: New Palestine, (1929), 83-84.

[2] Halász Zoltán, ‘Herzl’, Budapest: Magyar Világ Kiadó, (1995), 54.

[3] Novák Attila, ‘Theodor Herzl’, Budapest: Vince K., (2002), 72., 114.

[4] Shlomo Avineri, ‘Herzl cionizmusa’, Múlt és Jövő, (2010/1), 34.

[5] Amos Kiewe, Theodore Herzl’s The Jewish State: Prophetic Rhetoric in the Service of Political Objectives, Journal of Communication and Religion, (2003/2), 212.

[6] Herzl Tivadar, ‘A zsidó-állam. A zsidó-kérdés modern megoldásának kísérlete’, Budapest, Jövőnk, (1919), 4.

[7] Theodor Herzl: ‘Theodor Herzls Tagebücher 1895-1904’, Berlin, Jüdischer Verlag, (1922), vol. I., 7.

[8] Herzl, ‘A zsidó-állam’, 6-7.

[9] Herzl, ‘Tagebücher’, vol. I., 92.

[10] Weizmann’s letter to Ahad Ha’am, (14-15th December 1914), Weizmann Archives (Rehovot), 7-303.

[11] Herzl, ‘A zsidó-állam’, 8-9.

[12] Szabolcsi Miksa, ‘Nem kérünk az új hazából. Válasz dr. Herzel [sic!] Tivadar röpiratára’, Egyenlőség, (6th March 1896), 1-2.

[13] Yakov M. Rabkin, A Threat From Within. A Century of Jewish Opposition to Zionism, New York, Zed Books, (2006), 81.