71 years ago, British policemen at Petach Tikva were alerted to an attack against their colleagues at Ramat Gan. The perpetrator of the assault–which, apparently, was carried out in order to steal weaponry and cost no lives–was the Irgun, one of the pre-state paramilitary right-wing Zionist groups that worked for an independent Jewish state. Among the attackers was a certain Béla Gruner, a Hungarian Jew who was one of the last Irgunists to leave the Ramat Gan police building. As he was hurrying to join his comrades, a British policeman confronted him at the entrance of the police station and shot him in the chin. He fell into a ditch, wounded. And although this was the final time Dov Gruner–as he later became known–saw action, his story did not end here. He went on to become one of the finest examples of pre-state military heroism in Israeli history.[1]

Gruner was born in an observant Jewish family in Kisvárda, Hungary. His father, Jakab (Ya’akov) Grüner was a rabbi in the Austro-Hungarian army and died in Russian captivity in the First World War. Gruner studied in the local yeshiva, and was later driven by anti-Semitic Hungarian legislation to study abroad. He joined the Betar movement in 1938, and made Aliyah in 1941. After a brief service in the British army, he joined the Irgun in 1946: the organisation was then in conflict with the British Empire and Gruner turned against his onetime allies to liberate his country.[2]

He survived the potentially deadly shot and was taken to prison

After taking part in a previous attack in Netanya, Gruner participated in the assault against the Ramat Gan police station. He survived the potentially deadly shot and was taken to prison. His trial dragged on for almost a year, at the end of which he was hung in the Acre prison. Thus he joined the olei ha’gardom, that is, the ‘ones who mounted the gallows.’ Yet, his subsequent elevation to the pantheon of Israeli patriotism was not only motivated by the politics of memory that emphasized the role of the underground militia in ousting the British. It also happened due to the fearless, stalwart behaviour that Gruner demonstrated in prison and in court. ‘He was stronger than the gallows,’ Menachem Begin said in Ramat Gan in 1954, speaking at the inauguration of the now famous statue portraying Gruner as a lion cub fighting the mature lion of the British Empire. ‘Seven years after Dov went away, this statue embodies the freedom-fight of the nation…And the lion of Judah shall stand forever, to remind the coming generations of patriots [of his sacrifice].’[3]

Begin had a special connection to Gruner, from whom he received a moving letter of farewell from prison. The letter, written on small scraps of paper and quoted in a number of translations, partly proclaims the following: I shall know how to uphold my honour, the honour of a Jewish soldier and fighter. I could have written in high-sounding phrases . . . but words are cheap, and sceptics can say “After all, he had no choice.” And they might even be right. Of course I want to live: who does not? But what pains me, now that the end is so near, is mainly the awareness that I have not succeeded in achieving enough…[When] the the very existence of our nation is jeopardized, we must fight with all possible means. This is the only way left to our people in their hour of decision: to stand on our rights, to be ready to fight, even if for some of us this way leads to the gallows. For it is a law of history that only with blood shall a country be redeemed. I am writing this while awaiting the hangman. This is not a moment at which I can lie, and I swear that if I had to begin my life anew I would have chosen the same way, regardless of the consequences for myself. Your faithful soldier, Dov.’[4]

While Gruner bore his imprisonment with fortitude, many branches of the Zionist movement mobilised in his defence. Under the reference number 537/2292, the British National Archives keep a number of letters sent to the Colonial Office in protest of Gruner’s death sentence. Some famous Zionists–from the left and right-wing of the movement alike–begged for his life, as did his sister, Helene. Others were not so polite: Lechi, another right-wing Zionist militia, promised to execute British families residing in Cairo ‘one by one’ if their demands were not met. Another anonymous letter called Gruner’s British judge a Nazi and threatened to ‘hang him immediately.’ But in spite of the threats–and the warnings by British colonial officials about the impeding “state of terror” in Palestine–Gruner’s death sentence was upheld.[5]

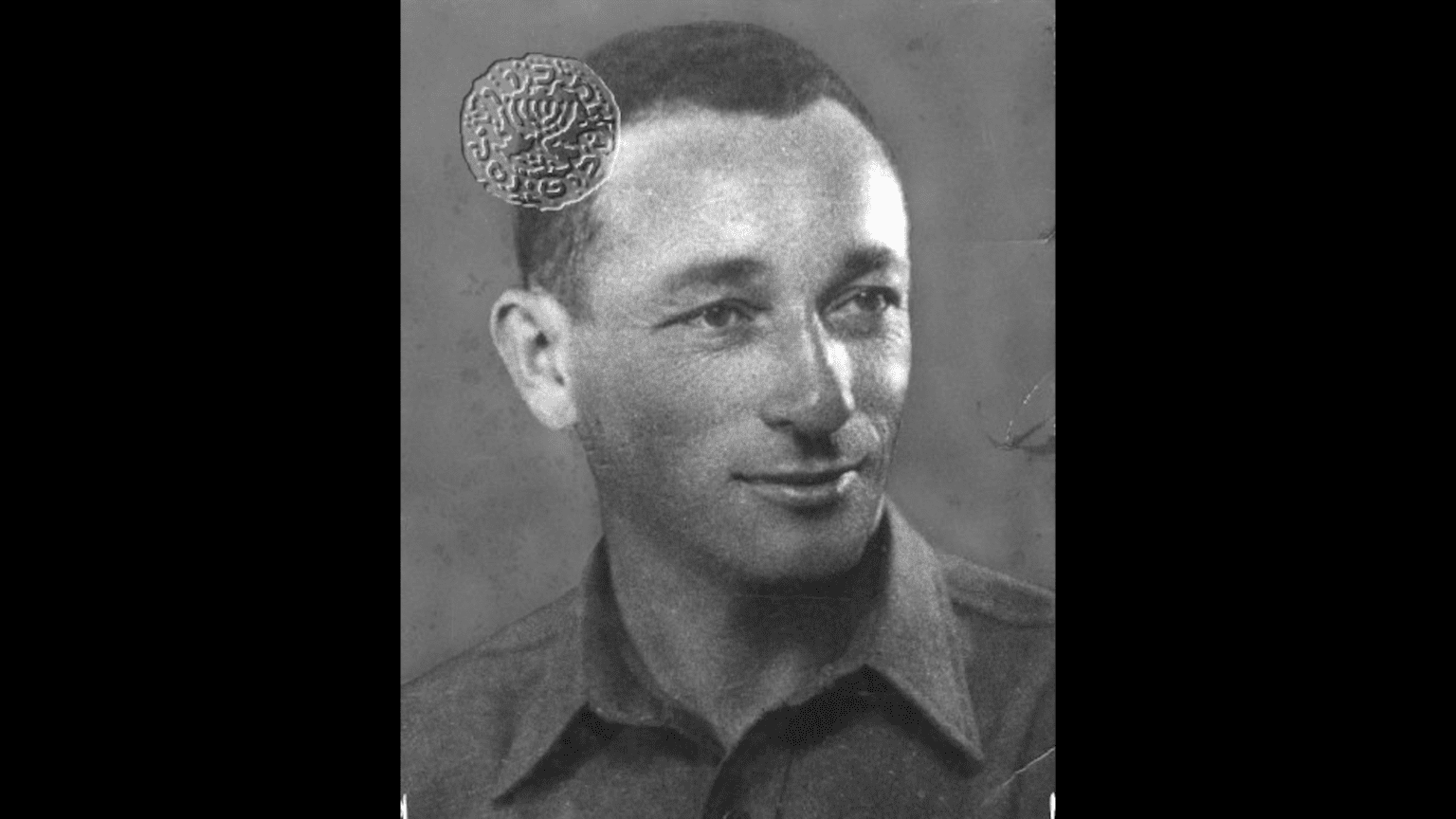

In prison, Gruner was visited by his sister. Helene wrote back to her relatives in the US that ‘I cannot see my brother Béla . . . except for Saturdays, for 15 minutes. It is horrible to wait for such a meeting for a week and then only receive 15 minutes. Barely have I said hello and I already have to say goodbye, and even that through a window with thick bars. His face is horribly disfigured. He cannot eat but takes it beautifully. He is a wonderful man, and I am so proud to have him as a brother.’[6] The Jabotinsky Institute in Tel-Aviv possesses a photograph of Gruner in prison: even though his chin certainly looks damaged, his face remains recognisable.

On 16 April 1947, shortly after midnight, the guards of Acre prison shook Gruner and three other Zionist militiamen awake. They were taken to a dimly lit room, where the gallows stood. Their final wish to be accompanied by a rabbi was not granted: therefore they asked, and were allowed, to sing Ha’tikvah, the song that later became the Israeli anthem. After their execution, cleaning personnel entered their cells, and on the wall they found an inscription: ‘To die, or to conquer the hill.’ The Irgunists quoted Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a poet and politician revered as a prophet among right-wing Zionists. In his will, Gruner left all his possessions–120 Palestinian pounds– to the Irgun.[7]

‘To die, or to conquer the hill’

But for all the respect commanded by Gruner’s name in Israel, not much has been reported on his trial and execution in his former homeland. The Hungarian Socialist daily Szabad Nép (‘The Free People’) reported that ‘the terrorist Dov Grüner and his three partners in deed were hung in the Acre prison today.’[8] Had the contemporary Socialist agenda not been one of militant anti-Zionism, maybe they could have recognised the importance of a Hungarian Jew having become a martyr of the emerging Jewish state. Among Gruner’s papers kept at the Jabotinsky Institute remain a few letters penned in his native Hungarian: in one of them he announces to his sister his joining of the British army. In spite of his radical Zionism and rejection of Diaspora life, he signed the letter as ‘Béla,’ an ancient Hungarian name with Slavic roots.[9]

Perhaps this indicates a mere family attachment; perhaps it signifies some lasting longing for the lost land of birth. But whatever compelled Dov Gruner to identify with his old Diaspora name, today this Hungarian Jew who went on to become one of the most famous martyrs of Zionism testifies for the resilient links between Eastern Europe and the Jewish State. Much remains to be uncovered in the history of Hungarian and Eastern European Jews and their contributions to the State of Israel, and many a lesson can be drawn from the sacrifice of Dov Gruner.

[1] For this story see: Tom Segev, ‘Why Inspector Denley cried’, Haaretz, 2 May 2008.

[2] On this see: J. E. S., ‘Dov Gruner – A Betari of Budapest, Tel Avivi, Jabotinsky Institute, (hereon cited as JI), K16-3/5, pp. 28-29, and K16-3/13, pp. 37-38, p. 48.

[3] JI, K16-3/13, pp. 68-69.

[4] Jerry A. Grunor, ’Let My People Go: The Trials And Tribulations of the People of Israel’ (New York: Universe, 2005) 127-128. See also: JI, K16-3/13, pp. 44-45.

[5] National Archives (Kew, hereon cited as NA), CO 536/2292

[6] JI, K16-3/5, p. 19.

[7] NA, CO 536/2292, Press Censorship Report on Comments on Executions.

[8] Szabad Nép, 17 April 1947.

[9] JI, K16-3/5, pp. 12-13.