In February 1947, the British Secret Service received a tip-off from ‘official sources’: Menachem Begin, the ‘notorious Palestinian Zionist terrorist’, had undergone a face transplant.[1] He was believed to have had the operation at a Swiss clinic with the help of a German doctor. ‘We don’t yet know what his new face will look like,’ the report concluded. The ‘official source’ was none other than a walnut farmer from Rechovot, Hilik Weizmann. He was the younger brother of the later Israeli state president, Chayim Weizmann, a Begin antagonist. But the story of the face transplant was also spread by the Hungarian-born Zionist writer Arthur Koestler (Kösztler)—a supporter of the right-wing Begin.

With the years, numerous tales and myths were fabricated, passed on and occasionally spread not only by Begin’s opponents but also his followers. The mere fact that his voluminous files, compiled by professional investigators in the British National Archives, contain more than 15 different biographies and eight pseudonyms of Begin, is a sufficient illustration of what a legendary and controversial figure he was.

The road to the office of prime minister led through Nazi bombs and Communist prisons, British bayonets and Tel Aviv hideouts, freedom fights and terrorism;

while Begin travelled this road, so understandably many legends were spawned about his life. Some of these he invented himself; some he simply picked and spread; others he vehemently denied. What is certain, however, is that his career and his deeds were surrounded by a multitude of contradictions, some of which still survive today in relation to his biography.

Menachem Volfovich Begin was born into a family of rabbis and merchants in Brest-Litovsk in 1913, and at the age of 15 he defended the founder of the right-wing Zionist movement, Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, with his own body when he was attacked by stone-throwing leftist Zionists. Begin was an esteemed member of the Betar movement in Poland, but it was his Betar leadership that was the subject of the first myths and accusations that overshadowed his life. According to the allegations, Begin, as a Zionist leader, left his community behind during the Holocaust and fled to ‘independent’ Lithuania to save his own life.

The accusation touched on a soar spot with Begin, as a cornerstone of his rhetoric and political views was the reference to the Holocaust, justifying his views based on the Shoah. When the Nazis invaded Poland, Begin fled to Lithuania, where he was taken prisoner by the Soviets in the autumn of 1940. Begin did not say why he fled Poland, and in his memoirs he stressed that he was under no obligation to reveal his motives. His critics have suggested that he left his former homeland out of cowardice, and that he was ashamed to talk about it. Yisrael Eldad (Scheib), Begin’s revisionist friend and fellow politician who fled Warsaw for Vilnius with Begin, said it was indeed a matter of shame, but in a different sense: Begin’s first reaction to the occupation was a ‘patriotic’ Polish response, calling on his fellow betarim (right-wing Jewish activists) to ‘dig trenches’ and take part in the defence of the city. While this would have been understandable from an assimilationist leader, Begin’s radical Zionist ideology rejected the idea that the homeland of Polish Jewry was Poland. For understandable reasons, therefore, Begin kept silent about why he had fled to Vilnius—probably to cover up his reaction that was contrary to the tenets of Zionism.

But later, as an Israeli politician, he felt that even this story was incompatible with his militant rhetoric. Begin was therefore fond of spreading the story that he, too, had been persecuted during the Holocaust. On one occasion he claimed that his parents were killed ‘before his very eyes,’ and on another he called on his fellow MPs in the Knesset to raise their hands if they were forced to wear a yellow star. ‘I had to!’, he declared. The first statement is certainly untrue, as Begin’s family stayed in Warsaw, so Begin, who was in Lithuania and then the Soviet Union, could not see them being killed. Begin would also often claim that his parents were killed in a river by the Nazis along with 500 others, but his sister Rachel Halperin told a historian that the story was ‘a myth’. She said their father was shot and their mother murdered in her hospital bed. The story of the alleged wearing of a yellow star is even easier to rebut: Begin was never once in any territory under Nazi rule, so he can’t have worn a yellow star.

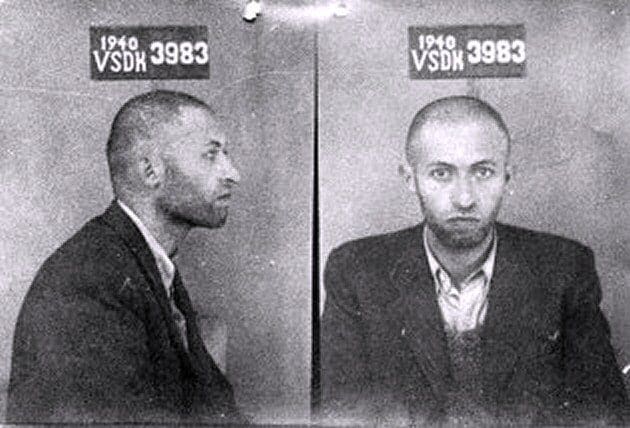

Begin was arrested by Soviet investigators in Vilnius in the autumn of 1940, which he recounts in his autobiography, White Nights.

He was sentenced to eight years in the Gulag and was only released when Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union and an independent army of former Polish soldiers under the leadership of Polish General Władysław Anders was organized.

In any case, another myth about Begin’s life, which British intelligence in particular tried to spread in the United States, stems from this period: the accusation of a communist past and of being in the service of Soviet intelligence. It is not entirely clear where these rumours originated: the earliest reference in British archives is to a Swiss communist newspaper, which reported in an article that Begin had been a member of the Communist Party in Poland as a young man.

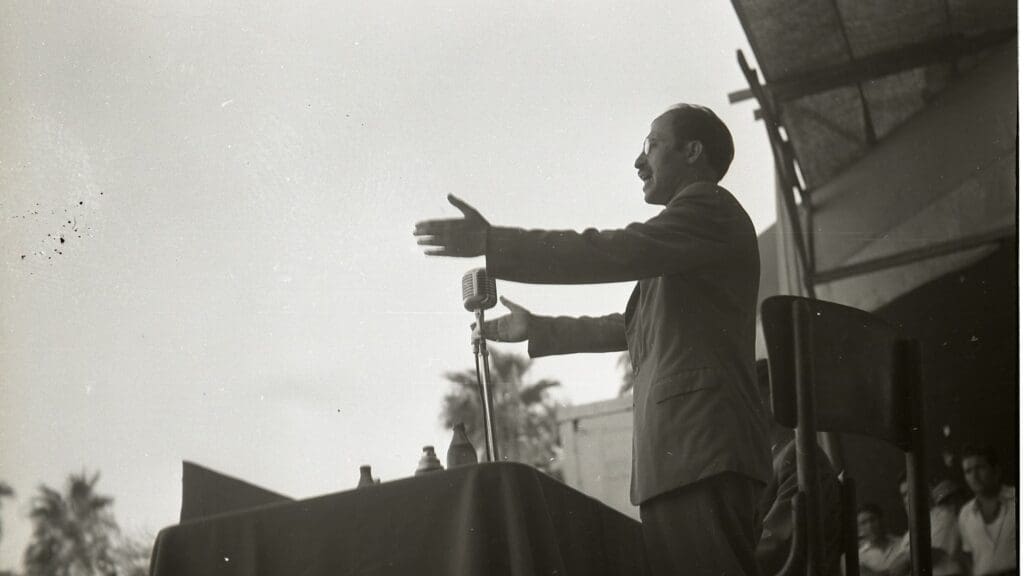

Later on, he moved to Palestine where he organized an armed revolt against the British. While Begin was careful to hide from the British secret service, changing his name and residence a number of times, many who wanted to could find him. Arthur Koestler was able to get an interview with him, and even recorded in his diary the information that Begin’s alias at the time was Yisrael Sassover. Koestler was allowed to speak to Begin in a darkened room; whenever he took out a match to light a cigarette, a bodyguard of Begin’s would step up to him and block the light of the match in his hand.

The British authorities sometimes came very close to catching Begin: once they searched every house in Begin’s street, but he, dressed as an Orthodox Jew, sat outside the door of his house and watched the soldiers from there. No one suspected a man sitting and observing the commotion calmly.

Menachem Begin had a lot of labels attached to him in his life. For his followers, he was one of ‘the most glorious and successful men in history’, while Koestler, who otherwise sympathized with him, considered Begin ‘a romantic Pole who taught his people how to die, but not how to live‘. Left-wing Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky once called him a ‘petty little fascist Polish lawyer or something’. But such extreme judgements about Begin have often been motivated by political ambitions and therefore do not help historical clarity. 110 years after his birth it is time to appreciate his values while not turning a blind eye to his flaws either.

[1] This article is based on the author’s essay ‘Menahem Begin legendás élete’ published in Issue 3 of Volume 7 of Világtörténet, accessible at http://real.mtak.hu/74113/1/Veszpremy_u.pdf.