The following is an adapted version of an article written by Barnabás Leimeiszter, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

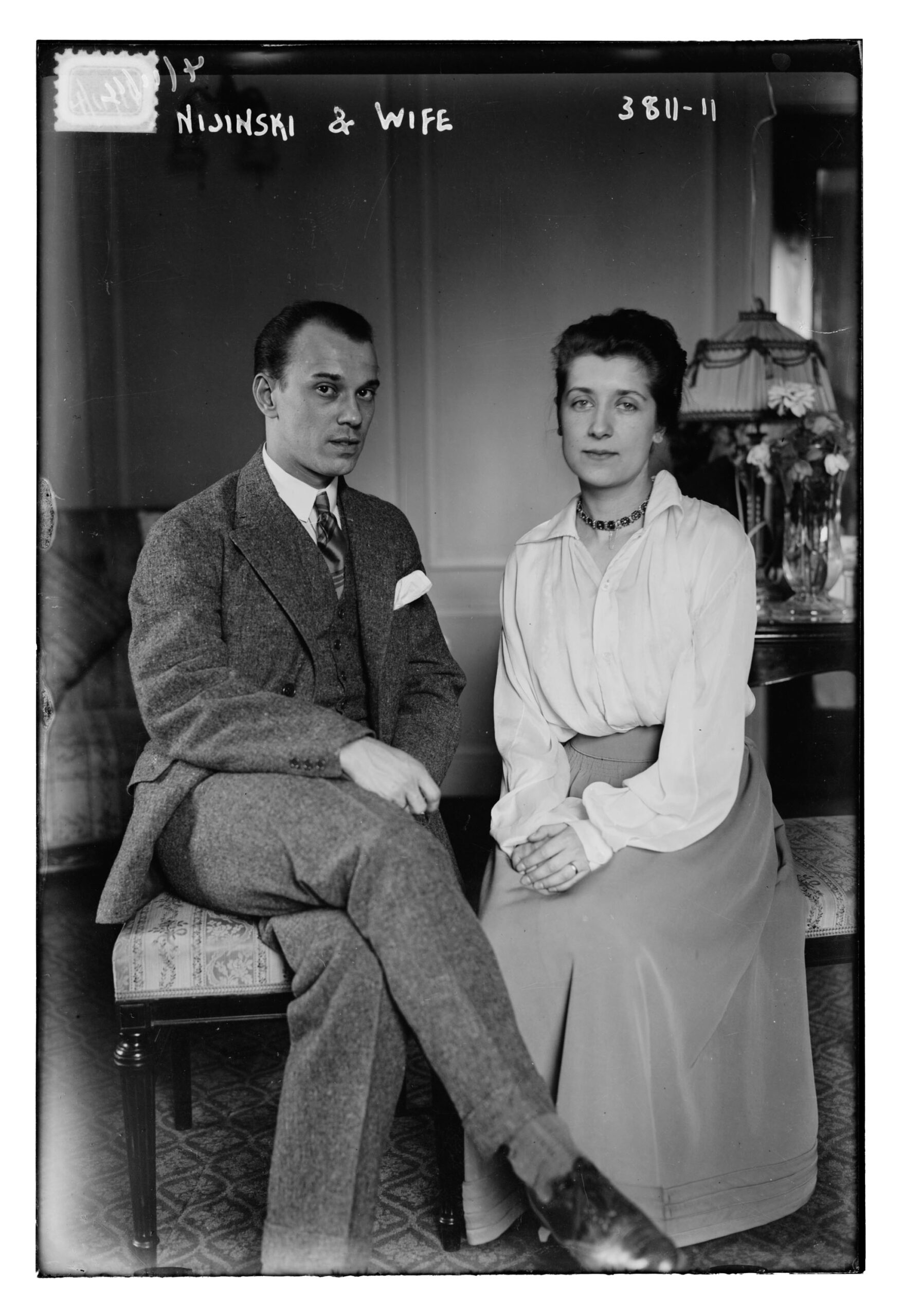

Vaslav Nijinsky, the top male ballet star of his era, married Romola de Pulszky, a descendant of the Pulszky family, who devotedly cared for the dancer suffering from severe schizophrenia.

Art historian Károly (Charles) Pulszky, or as his friends called him, Charley, is one of the great tragedies that abound in the annals of Hungary during the dualist era: As peaceful and intimate as the world at the turn of the century seems in retrospect, so many wasted talents and careers that ran aground testified to the negative energies lurking beneath the surface. Born in exile in the West in 1848, and then moved to Hungary with his family a few years before the Compromise, Pulszky’s life came to a standstill when he was unable to account for the public funds entrusted to him for expanding the collection of the National Gallery, and it turned out that he had also purchased a fake Raphael painting at an exorbitant price. He was likely guided more by carelessness than by any dubious intentions, and it later became clear that the painting in question, Portrait of a Man by Sebastiano del Piombo, was of considerable value and remains the pride of the Museum of Fine Arts’ collection to this day. In any case, Pulszky, broken in spirit and mind, fled from the accusations all the way to Australia, where he spent his days as a travelling salesman before shooting himself in the heart in the suburbs of Brisbane.

Károly Pulszky’s wife was the celebrated actress Emília Márkus. Their younger daughter, Romola de Pulszky, met the already world-famous Vaslav Nijinsky during Sergei Diaghilev’s ballet company’s guest performances in Budapest in 1912.

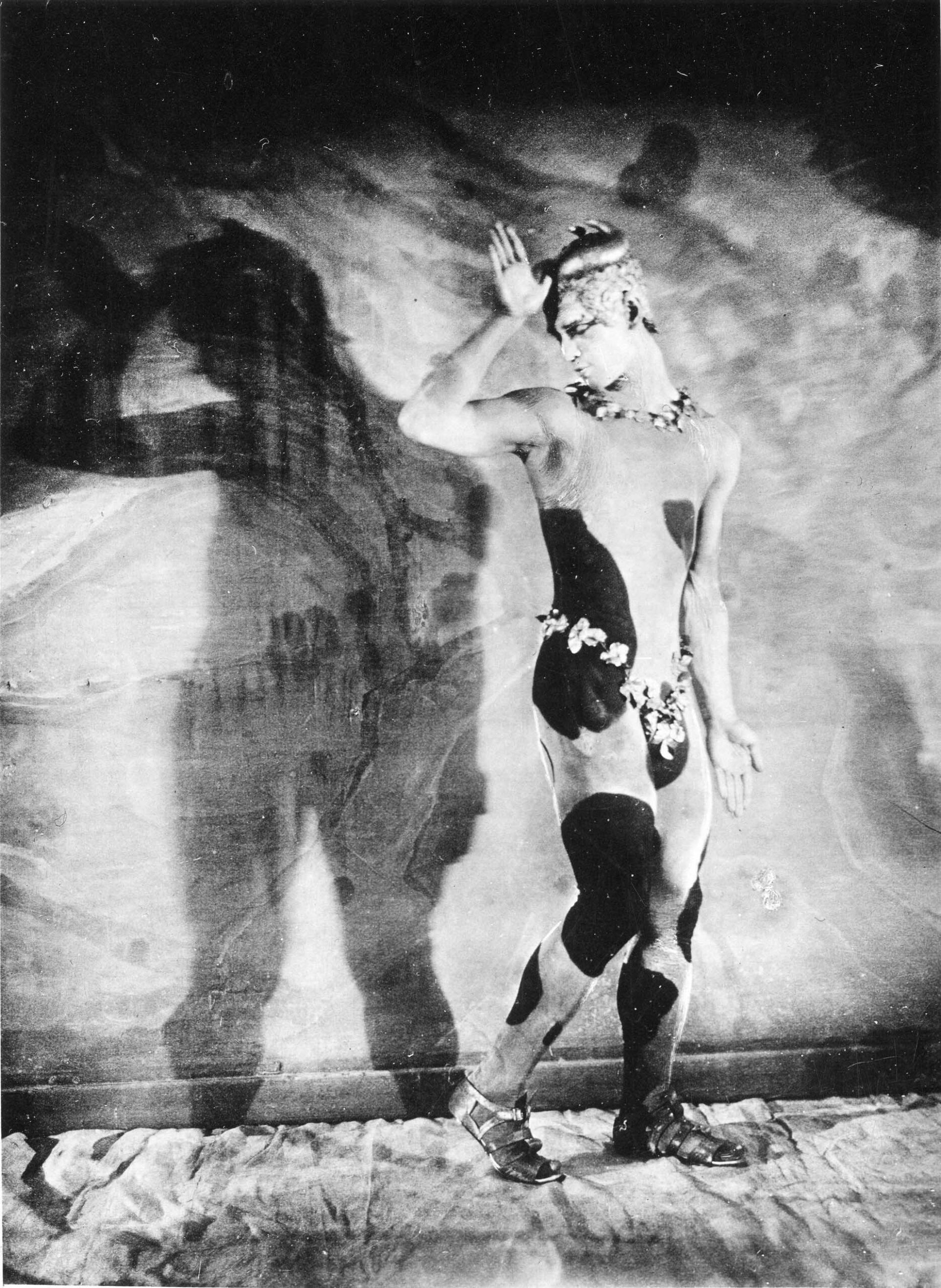

One of the greatest male dancers of the twentieth century was born in Kyiv in 1889 to Polish parents. He rose to fame as a member of the Tsarist ballet, and then, under Diaghilev, in ballet productions choreographed by Mikhail Fokine and with sets by Leon Bakst, he became an icon of modernist art.

‘Suddenly, a slender, lanky, cat-like Harlequin took possession of the stage. Although a painted mask covered his face, we immediately realized from the expressiveness and beauty of his body that we were in the presence of a genius. It was as if the entire audience had been struck by lightning. Intoxicated, spellbound, gasping for breath, we followed this superhuman being, the faithful spirit of this Harlequin incarnate, useless and lovable,’ Romola later recalled. The dancer made such an impression on her that she joined the Diaghilev company, which was soon to embark on a tour of South America. Her relationship with Nijinsky started to deepen during the Atlantic crossing: as the Keleti Ujság newspaper in Cluj-Napoca euphemistically put it, ‘the magnetic power of her feelings…drew him to her…turning his instincts in a different direction.’

‘[Nijinsky] rose to fame as a member of the Tsarist ballet, and then…became an icon of modernist art’

Upon arriving in Buenos Aires, much to the annoyance of Diaghilev, who was having an affair with Nijinsky, the young couple immediately tied the knot. The wedding night, during which the dancer left Romola alone after kissing her hand, did not bode well for their sex life. However, in 1913 (the year when Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, choreographed by Nijinsky, was premiered on the Champs-Élysées, and the premiere, which degenerated into a public brawl, became a milestone in the history of the avant-garde), their daughter Kyra was born. When World War I broke out, they moved to Budapest, to Emília Márkus’s villa in Hűvösvölgy, where the dancer was placed under house arrest as a citizen of an enemy country. Later, after lengthy diplomatic complications, Diaghilev managed to arrange for Nijinsky to be released for an American tour, which, as it turned out, marked the end of his career. While staying in Switzerland, his mental problems became so severe that he ended up in a mental hospital. He suffered from severe schizophrenia and was overcome by religious ecstasy—‘Bleuler, Wagner-Jauregg, Kreplin, Ferenczi, Freud, and Jung were all unable to help him.’ A poignant document of his madness is his diary from 1919, which has been published several times in Hungarian. Nijinsky returned to Budapest for ten months in 1920, when his second daughter, Tamara, was born.

Márkus and his second husband cared for him devotedly. The dancer and actress’s favourite game was to guess which tram would arrive first when they transferred at Hidegkúti Road on their way back from the city.

There were periods when he was clearer, but his condition did not improve significantly: he once had a fit of rage in the middle of Váci Street. For many years, he vegetated as a ‘walking dead’ in Bavaria, in the sanatorium of Kreuzlingen. Then, in the second half of the 1930s, as Viktor Lányi wrote in the Sunday edition of Pesti Hirlap, ‘there were signs of an unexpected and welcome improvement. His consciousness became clearer, his speech improved, and he began to show interest in dance, music, family, and acquaintances.’ Nijinsky underwent the controversial insulin shock therapy of Manfred Sakel, which triggered quasi-epileptic seizures. Meanwhile, Kyra, who was following in her father’s footsteps as a dancer, married Igor Markevitch, a famous composer and conductor who was still at the beginning of his career and who, if we are to believe the report in Uj Nemzedék, asked Emília Márkus for her granddaughter’s hand. The wedding was held at Matthias Church. Krya and Igor’s marriage was short-lived, but they had a son, Vaslav, named after his grandfather.

‘Nijinsky underwent the controversial insulin shock therapy of Manfred Sakel, which triggered quasi-epileptic seizures’

In 1940 Nijinsky and his wife moved back to Hungary as the foundation financing his sanatorium treatment was unable to obtain funds due to the war, and they were denied entry permits to the United States. Upon their arrival, a series of photographs captured the former ballet dancer, now barely recognizable as such, in the company of Romola and Emília Márkus. According to a report in Új Magyarság, Romola still believed at that time that her husband would one day return to the stage.

‘Afterwards, we had tea with Nijinsky. He sat in his grey suit, maintaining his usual stiffness, neither standing up nor offering his hand. His Tatar face was clouded with indifferent apathy, and he gazed into the distance with his dull, beautiful brown eyes. What could he have been seeing? He did not participate in the conversation, but he listened and laughed heartily from time to time,’ the author of the article reported.

The couple lived with the Márkus family in the Lepsény area for a while, then returned to Hűvösvölgy for a short time in the summer of 1944. However, they did not stay long in the villa, which was later destroyed by bombing, as the daily air raids thoroughly frayed Nijinsky’s nerves.

After the war, rumours spread that the Germans had executed Nijinsky as an incurable patient. Fortunately, this turned out to be false. The family moved to a quieter village near Sopron, but the nerve-wracking reality of war soon caught up with them there as well.

According to an article published in the weekly magazine Szinház in November 1945, the dancer only calmed down when he heard Russian spoken around him, and he talked and drank vodka so ‘lively and casually’ with the Soviet soldiers, who had no idea who he was, that there was even hope for his recovery. He allegedly danced his last dance in front of them.

From Sopron, they travelled to Vienna in a car provided by the Soviet command, and then moved to England. Nijinsky never recovered and died in 1950, while his wife survived him by 28 years. Their younger daughter, Tamara, grew up in Budapest and made her debut as an actress in the 1930s in the theatres of Pest. At the end of the war, despite Márkus’s disapproval, she married her colleague Miklós Szakáts, who was also involved in the resistance movement. She worked at the Vígszínház and the State Puppet Theatre, then in 1956 she defected to the United States with her daughter, Kinga Szakáts and her second husband. She died in 2007. Kinga Szakáts lives in Arizona and visits Hungary from time to time, keeping the memory of her famous ancestors alive.

Famous Emigrants in Budapest

In 2018 Ralph Brewster’s memoir, entitled Wrong Passport: Adventures in Wartime Hungary, was published in Hungarian, in which the music lover recounts his years spent in Hungary between 1940 and 1944. Strictly speaking, he cannot be considered an emigrant, as he had no ‘home’ anywhere. He was a direct descendant of William Brewster, leader of the first settlers who travelled to America on the Mayflower, but his immediate ancestors had already been living a nomadic life in Europe. By chance, Ralph was born in Italy, so he became an Italian citizen. In 1942 his residence permit was revoked, but Brewster, a staunch anti-fascist, refused to comply with the consulate’s request to enlist in Mussolini’s army. In his book, he outwits Budapest landlords and detectives in his search for accommodation and visits his acquaintances one by one. During his adventures, we also meet German spies, Balázs Lengyel, who married Ágnes Nemes Nagy, and his family, the luxury-loving bishop of Szombathely, János Mikes, László Almásy, who mourns his son who fell on the African front, the Christian middle class, the Jewish intelligentsia, and the many interesting figures of the Budapest gay scene, which Brewster knew intimately.

Joe Turner, jazz pianist and former member of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington’s bands, performed in Budapest in the 1930s and married a Hungarian woman. They caused quite a stir on the streets of Pest. In 1949 he returned to the Hungarian capital for six months, where he was reunited with his wife and daughter after nine years. Haladás refers to little Rita’s unusual situation: the little girl, ‘whose great-grandfather was a slave, was threatened with the yellow star in the age of “enlightenment”’. Tibor Bartos also mentioned Turner playing in the Újpest espresso bar in his memoirs: as he wrote, he received an Ellington record as a gift from the musician.

Bobby Fischer, the reclusive American chess genius, was persuaded by a Hungarian teenager, Zita Rajcsányi, to return to playing; in 1992 he agreed to a rematch with his former legendary opponent, Boris Spassky. However, because the match was held in Yugoslavia, which was already at war, Fischer was placed on the American sanctions list. He settled in Magyarkanizsa and then Budapest, where he stayed—suffering from increasing paranoia—until the turn of the millennium, maintaining contact with the Polgár family and Péter Lékó. In 1999 a Calypso Radio presenter interviewed him, but despite attempts to steer the conversation towards current affairs in the chess world, Fischer, who was half-Jewish, kept talking about the Zionist world conspiracy until his interviewer hung up on him.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.