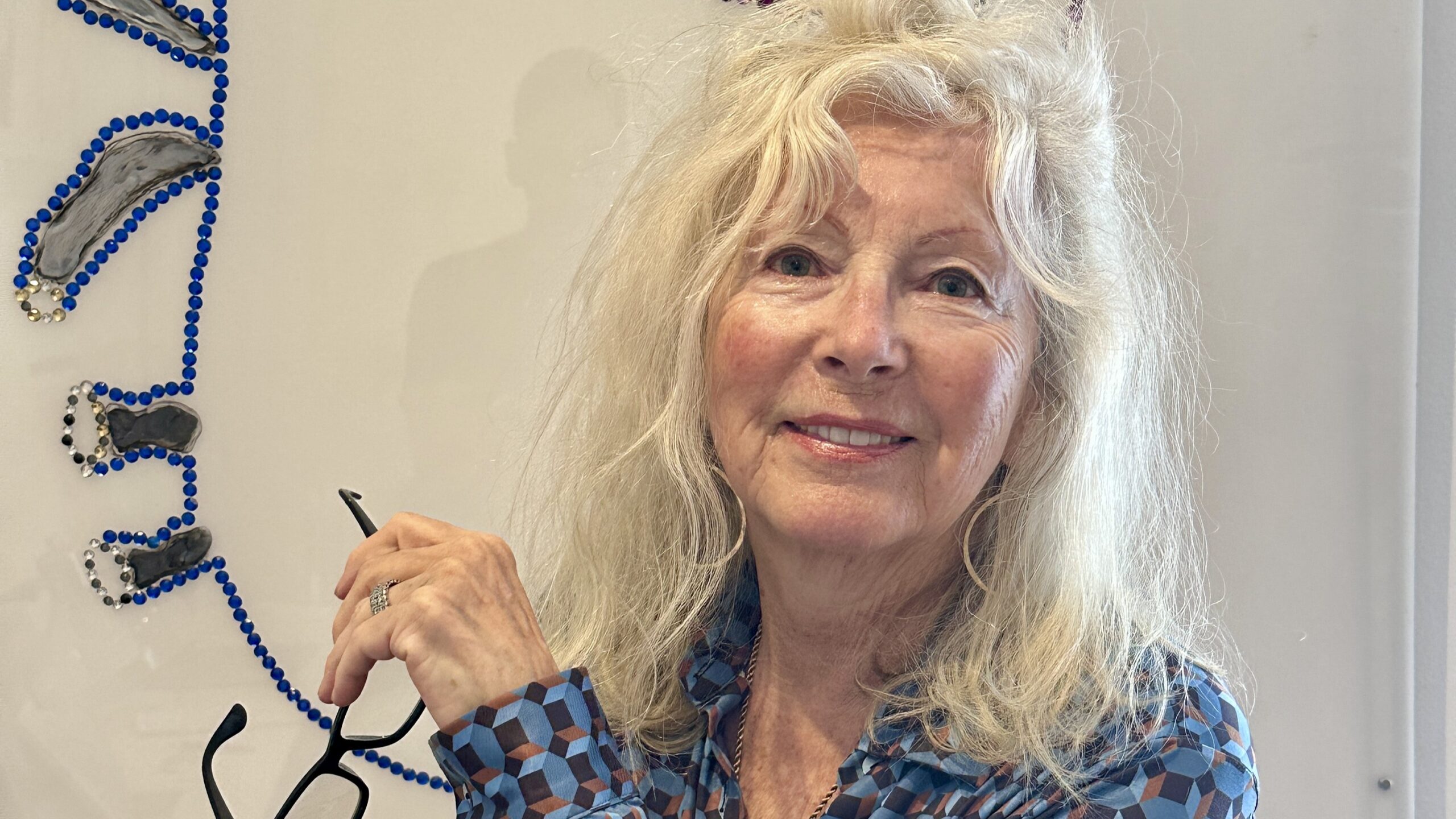

The following is a translation of an interview conducted by Éva Szilléry, a cultural journalist and fellowship holder of the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

Hungarian contemporary artists find it difficult to establish a permanent presence in New York, mainly for financial reasons. On the other hand, Zsuzsanna Csikós Nagy, aka Suzanne C Nagy, a visual artist and gallery director living there since the late 1970s, believes that Hungarian artists living in Hungary want to exhibit in the visual arts capital primarily to diversify their portfolio. Cultural journalist Éva Szilléry met the artist at The National Arts Club in Manhattan, where she collaborates on projects with Hungarian contemporaries and regularly exhibits her works at fairs in Budapest. The artist also spoke about how she thinks cultural life has changed over the past 40 years and where she thinks the Hungarian community in New York has gone.

***

It’s said that in New York’s business and social life, what really matters is being a member of one or two traditional clubs—such as The National Arts Club in Gramercy Park, where we’re meeting right now. Do you share that view?

New York is a very free-spirited city, you can’t say that being a member of a club is a distinguishing factor. Of course, there is prestige in being a member of a quality place, because you can be connected to a strong, cohesive group. The National Arts Club mostly admits artists; it took me two years to get in. I would have to pay to have a solo show here, but as a club member, I can be included in group shows. The openings are private, but the exhibitions are advertised and free to visit.

You turned your attention to fine arts only later in your life, as you are an economist by profession, and also studied filmmaking in Budapest. How did you change direction?

I met my Hungarian-born American husband in Budapest. I decided to move here and live my life with him in New York. After university, I studied at MAFILM’s special class with István Nemeskürty as a screenwriter and producer. When it was certain that I would move to the United States, István Nemeskürty thought that he should not ‘lose’ me and sent me to Hungarofilm to represent the Hungarian connections. I had a liaison role: I brought American films to Hungary that could be shot at home at a fraction of the original cost. Hungarian filmmaking skills were always very high. In essence, I did what the Hungarian National Film Institute has now perfected and made world-class by organizing filming in Hungary. My economic thinking made it easy for me to make budgets, and I made four Hungarian-produced films in total. The fourth one, titled Grizzly II: Revenge, shot in Pilisborosjenő, ended in a scandal because my American partner disappeared, and although the $400,000 for the filming costs had been paid, there were many disputes between me and the television about other incidental expenses. Years later, after all the confusion, my former partner wanted to finish the film with me, but I didn’t talk to him anymore. During the Covid epidemic, I decided to finish it myself. The film won an award at the Indie Film Festival in Los Angeles, and I signed a ten-year contract with a distributor. It was no longer an emotional issue for me at the time, but I don’t like unfinished business.

Was it because of this scandal that you changed your career and went into fine arts?

At the time of my film work, in 1983, I already had a solo exhibition of my own works in Budapest. Filmmaking is such a demanding profession that I finally chose fine arts. The turning point, however, came with the death of my husband. He had a huge collection of tapestries and 17th-century textiles. I took over the gallery and had great success with it. I became more and more immersed in antiques. Later, I started to work with legacies. By then, I was working as an expert at Christie’s, with 11 restorers helping me. In addition to legacies, I was also interested in contemporary art. I had my gallery at the Manhattan Art&Antique Center at the intersection of 56th Street and 2nd Avenue in New York, a very beautiful and well-protected three-storey building. One of the largest showrooms was ours. In the meantime, I launched a purchase of legacies, and after the regime change, I organized an exhibition of Miró and Chagall in Hungary, in collaboration with the Erdész Gallery. I am still in working contact with the gallery director, László Erdész, to this day. Back then, the way to bring artworks home was to send them to London to enter the EU, and from there to Hungary. About four years ago, I bought an apartment on 23rd Street, which I converted into a gallery with two large rooms.

‘Filmmaking is such a demanding profession that I finally chose fine arts’

You exhibited at the Kunsthalle in the early 80s. Were you free to travel home?

Yes, because I went with a green card, as I married my American husband in Budapest. I signed a representation contract with Hungarofilm and could come home practically any time.

A few years ago you displayed your collection in Várpalota, with prints by Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso, and Miró. Why did you choose to exhibit at the Várpalota Gallery?

I run a large exhibition space in Badacsony, hence my good relationship with the people of Várpalota. For four years I organized free exhibitions of Picasso, Dali, Chagall, and Miró from my collection at the Egry József Memorial Museum in Badacsony. With the proceeds of these exhibitions, the town managed to buy and rebuild the museum, and I was elected honorary citizen of the town. The Várpalota Art Gallery also followed my work, and that is how my collaboration with them was born. On 8 May we exhibited Miró’s paintings in the beautiful synagogue in Várpalota.

How much has the art trade changed over the decades?

From the very beginning, I have been the one who has received the American legacies; the Hungarians do not reach out to me. Serious work can only be sold if I can put a completely fresh provenance on it. I currently have two Modigliani paintings whose provenance is being checked in Switzerland. Today, because of the many abuses, old provenance documents are not accepted anymore. The artworks in question came into the possession of the gentleman who entrusted me with his estate in the 70s, and I have to carry out a recent provenance examination on the painting. Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s have sold several works that have turned out to be fakes. A few years ago, for example, there was a debate about the authenticity of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, and many experts still do not believe that it is entirely original or that it can be considered a work by Leonardo because of the over-restoration carried out on it.

Wasn’t there as much abuse in the 90s as there is today?

It was a completely different world then—with the advent of the internet and the rapid flow of information, everything is revealed very quickly today. When I started in this business, there was not so much controversy about the authenticity of artworks. Nor was it spreading so quickly—prematurely—if you came across something of great value.

Are you specialized in European modernism?

The great masters of European modernism have made the biggest impact on American modern art, so I see a lot of work from that period in art history. Many great artists came here after fleeing the Second World War, such as Marc Chagall, who fled the German occupation and lived in New York for most of the 1940s. In the 1950s and 1960s the European school of modernism provided the basis for the expressionist movements that were very widespread here.

You call yourself an environmental artist. What exactly does that mean?

I work primarily on nature conservation. I went to a very high-quality art course at the School of Design of the New York Art Students League. My work on environmental issues is a way of raising awareness of the need to think long-term about the living world around us. I look at the process of human intervention in the natural environment. It’s very important that I use my work as a call to action because I’m increasingly concerned about the destruction of nature. I’m interested in how the natural environment will evolve on a global scale and whether we are aware of the process that is taking place. As I don’t make a living from my own work, I can afford to think in terms of projects. A few years ago, in Badacsony, where I set up a large 150-square-metre studio, I realized an art project reflecting on forest fires with 18 young people from public institutions. I organized this project as part of the Talent Deserves a Chance mentorship programme, in which young people made a living tree from dead wood. You would think these trees would be destroyed, but because their roots remain, they can quickly regain strength. This year I’m involving more talented children, also from public orphanages, in an installation called the Forest of Souls. This work will be exhibited in different cities across the country.

Do you consider it important to participate in social movements?

It’s important to join forces, and I always try to help. During the red mud disaster, I worked as a volunteer in Devecser. It was moving to see how the people in the lower part of the village waited patiently for a solution while we shovelled the mud. The disaster had a big repercussion here in New York, and I exhibited photos documenting the united work. I took a lot of pictures of it, which I exhibited in the Madison Avenue gallery at 82nd Street, but I also took the photos to Badacsony and Várpalota.

How well can Hungarian contemporary artists get into New York exhibitions today?

It depends a lot on how well one fits into the trend because they are quite strongly attached to the dominant trends in New York. With the Ani Molnár Gallery, we’ve recently started working on getting Tamás Konok’s work known. We thought it could work here. However, even if it has its message, geometric art doesn’t have a culture here. Additionally, the fact that Konok is a well-known artist in many parts of Europe, with a strong track record of success in both domestic and European markets, also contributes to this. Thus, this project is dormant for the time being.

‘I’m a Hungarian art lover, and I collect the artworks of Hungarian artists’

Meanwhile, Hungarian artists have become internationally famous in geometric art, especially in op-art, such as Victor Vasarely, János Fajó, and István Nádler. Do we hear about them here today?

Not very widely. I bought a lot of Vasarely’s watercolour sculptures and acrylic paintings at a time when Hungarians didn’t even want to hear about him, but he was already a big deal in Paris. You cannot say that there are Hungarian contemporaries who really matter in New York at the moment. There are plenty of artists at home who are prepared and would otherwise fit in with the trend, but as it costs a lot to bring and keep their work here, contemporary artists cannot really be present in New York. I recently wanted to bring one of them here, but in the end, she didn’t have the confidence to keep her work here for long. Contemporary Hungarian artists who live at home don’t even want to stay here long term—they would rather have it in their portfolio that their work was out in New York. I’m a Hungarian art lover, and I collect the artworks of Hungarian artists, but the internationally renowned names mentioned above can primarily be found among the collections of Hungarians here.

What are the dominant painting trends in New York right now?

Abstract expressionism still largely dominates painting. Minimalism with simpler compositions and shapes can be considered fashionable. Simple colours, clean compositions. In addition, intellectual conceptual works can also make a big impact. One has to visit New York’s gallery district to see how different the world of art is here from back home. But we also see how talented Hungarians are in their own milieu. What makes it different? The same that makes European, especially Central European, thinking quite different from American thinking. Although the world has become globalized and its issues are universal, the American artistic attitude is completely different here. There is an attitude of the artist—that may be the difference in thinking—hence the emanation and message of the work, which is different from the Hungarian one.

Several contemporary Hungarian artists are also invited to the Affordable Art Fair, which was held in New York in March, but is also present in several major cities. There is a stereotype in the domestic art world that this art fair categorizes the artist in the cheap sector, from which it is not easy to break out. How do you see it?

Maybe it’s a Hungarian way of thinking, but in America, there is no such thing as pigeonholing an artist because they have participated in an affordable fair sometime. I have not encountered such an attitude here, but I should add that in America, there is no such thing as ‘embarrassing’ in the first place, at least not in the way we use it back home. Here, there is a much stronger curiosity about the creators rather than criticizing them. I’m quite certain that the artist wouldn’t categorize himself in a way that limits his ability to progress further. I wouldn’t exhibit at the Affordable Art Fair myself anyway, not because of the cheapness, but I miss strong reflections there, as greater emphasis is placed on decorative painting. I like the fact that VOLTA Art fair, NADA, or New Art Dealers Alliance, and Frieze Art Fair are more about conceptual art. They jury the work before an artist gets into the fair. I was approached by a lot of galleries after the show, and I still exhibit twice a year in Chelsea. These exhibitions consider it more important to bring the power of art. History has shown that great artists and good work survive, and that someone can be discovered even in their 80s. It is also in the Hungarian way of thinking that an artist has to come from the University of Fine Arts to be accepted by the profession. This does not exist here either; self-taught artists, if their art is strong, are just as much a part of the profession as university graduates. For example, Gagosian Gallery, a major gallery network for modern art, recently saw a painting online and put on a huge exhibition of an unknown artist who has since become a huge success. It’s Anna Weyant, whose works sell for as much as $1.6 million at auctions today.

Róbert Berény’s work appeared in an American film, in Stuart Little, and was brought to Hungary after that. It evoked reactions in the American press as well. Have you heard about this?

No, it remained a domestic matter.

‘Here, there is a much stronger curiosity about the creators rather than criticizing them’

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is currently staging a major exhibition dedicated to abstract expressionist painter Jack Whitten. Is he a big deal out here? Which contemporary abstract expressionist influenced you the most?

Jack Whitten is a representative of the black abstract movement, which is to say that he sees things from the perspective of a subculture of society; his work is part ethnic and part universal. He’s not mainstream, but he has very universal themes, and that’s why he’s going to remain famous. For example, he has a huge painting right now of the demolition of the twin towers in New York at MoMA, which is a poignant and popular piece. Personally, I am touched by the works of Andy Warhol from the 50s, Willem de Koon from the 70s, and Kara Walker’s works on consumer society. And I like Lorina Simpson because social issues are at the heart of her work.

In the 80s the city was full of avant-garde artists and performances, according to the Hungarian artists who moved overseas at the time. In contrast, is the art and art scene in today’s New York dominated by art fairs and business?

There are so many galleries, open every Thursday, and an incredible number of artists. Indeed, there isn’t one standout ‘ism’ that amazes everyone. In that sense, it’s true that the 80s were a stronger period for art in general worldwide. Technology has changed a lot, so mixed media and digital art have become dominant in creative arts as well. In Hungary, by the way, it is followed by artists brilliantly.

Since the appearance of the dissidents in 56, there has been a Hungarian quarter and a Hungarian community here. Has this community disappeared, or does it still exist in the art scene today?

We don’t have that very community that was formed around 80th Street back in the day, where the Hungarians had lived. Those few streets were called the Eastern European block. There were at least ten good Hungarian restaurants in the city that survived into the 1980s. They were really connected by their anti-communist attitude. I’m a fan of Hungarian things, but I wonder how strong this feeling will be in the generation after me, for example, in my daughter. I have a very good relationship with the Liszt Institute, and they can still bring Hungarians together through culture. However, there is not a single Hungarian cultural institute that is a permanent exhibition space, which the Czechs, for example, have created for themselves (Editor’s note: Czech Center New York), and which works fantastically. If there were such a thing, contemporary artists could stay here for a longer period and get better integrated into the circulation.

Related articles: