In the first scene of Richard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin, premiered in 1850, German King Henry the Fowler I (reigned 919–936) is preparing to fight the Hungarians, who have been harassing the western world with their destructive campaigns since 899. This has a long history in medieval Bavarian tradition, where the hero of the defence is not the king, but a saintly count named Rasso. Of course, Rasso (also known as Rath) comes from the world of legend, as the Bavarian leader who repeatedly defeated the Hungarians and who, at the end of his life, went on a pilgrimage and founded a monastery. In the Benedictine monastery he founded, he died in the village of Grafrath (‘Graf’ meaning ‘count’ in German) on the island of Wörth on the Amper River in Bavaria, which is named after him today. He was buried there, where his tomb became a popular pilgrimage site even without official canonization, with a register of miracles kept between 1444 and 1728 recording more than 12,000 miraculous healings.

The most important dates of his life are also uncertain, as in Grafrath his feast day was 19 May, elsewhere 19 June, traditionally understood as the day of death. As for the year of Rasso’s death, we know about different years as well, such as 854, 954, or 1050, which is not surprising for a partly legendary person. Researchers prefer to place the life of the historical figure in the 9th century, in the Carolingian period, when he was remembered in connection with the Avar–Franconian wars fought between 788 and 803 in the Transdanubian region of present-day Hungary by Frankish Emperor Charlemagne. Rasso is associated in legend with King Henry I of Germany, but even more so with Prince Henry I of Bavaria (r. 947–955), and thus became the commander of a Bavarian victory in 948. The German annals of the same period do indeed mention a minor Bavarian victory, but Rasso’s name is not mentioned there. Since King Henry, in alliance with the Hungarians, rebelled against King Otto I, it is possible that he was made a hero of the battle against the Hungarians, along with Rasso, to honour his memory. The Baroque period saw the birth of the artistic depictions of the tradition of Rasso’s alleged victory over the Hungarians in 948.[1] Thus, 18th-century ceiling frescoes commemorate the warlord Rasso in Grafrath and Andechs, among other places. What they all have in common is that they highlight Rasso’s celestial intercession in battle.

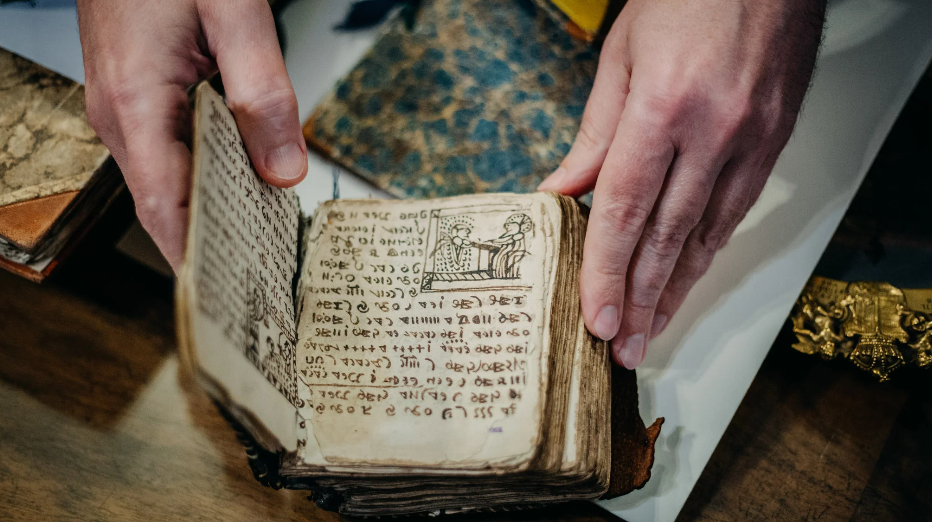

This different tradition can be explained by the late record of the legend of Rasso, especially the fictitious chronicle of Albert von Diessen (c. 1400), and even the ceremonial raising of his corpse (elevatio) only in 1468. Modern anthropological research has confirmed the enormous size of his skeleton, which is nearly two metres high, which may have been proof of his valour and invincibility in battle during his lifetime. The efforts of the ecclesiastical community that preserved his body and served as a place of pilgrimage until modern times have coloured and enhanced his memory. Later legends tell us that, after he had distinguished himself in the battles of the Holy Land, he brought back with him a large number of relics from Constantinople, Rome, and Milan as imperial honours.[2]

‘It is possible that he was made a hero of the battle against the Hungarians, along with Rasso, to honour his memory’

Among the relics, the most interesting are the historical notes associated with the so-called Victory Cross attributed to Charlemagne. According to these, ‘King Charlemagne, who had himself been brought by an angel to fight the infidels, sent this cross to his son King Pippin in this region, so that with it he might triumph over his enemies in the time of Count Rasso. Over time, Count Rasso went to Hungary to defeat the infidels, and he took this cross with him to Hungary. There he abandoned it, lost it, and the cross remained hidden underground until the time of King Stephen of Hungary. This cross then appeared to Stephen, and on that spot the first church of Hungary was founded.’ The cross is still preserved in the Benedictine monastery of Andechs, but it was actually made later, in the 1140s, according to historical research.

Most of the information about Rasso’s role in the battles against the Hungarians can be found in the Latin chronicle of 1521 by Johann Turmair, known as Aventinus. According to the text, the King of the Hungarians invaded Bavaria with two armies, which were routed by the Bavarian Prince Henry. To commemorate the great victory granted by the heavens, Henry and his commanders, including Rasso, were sculpted in plaster, and the statues were placed in the nearby church of Mauerkirchen. The statues actually stood in the church until 1865, when a fire destroyed them, along with the ceiling fresco of the knights. The churches also housed the weapons attributed to them, which may also have inspired the creation of legends, as the armour of one of them could be seen in Neumünster, the burial place of Prince Henrik of Bavaria, until the early 16th century.[3]

Reliefs of the battles against the Hungarians also decorated the Knights’ Hall of the Dollinger House in Regensburg around 1300, but they were accompanied by a new legend in which Rasso’s person was replaced by a local knight, Hans Dollinger. In the time of King Henry, Dollinger fought a knightly duel with a pagan and defeated him. As the tradition developed, these pagans were called Huns, Hungarians, Turks, and Cracos, after the word for ‘dragon’ in Latin (‘draco’). According to Johann Sigismund Brechtel (1560/70–c. 1637), who was the first to record the story, King Henry I was making peace with the Hungarians in 930 (correctly 926) when a giant warrior called Craco, who had risen from the ‘Huns’, called for a duel from the opposing camp: ‘It happened then that among the Huns there was a distinguished, mighty and strong man, named Craco, whose height was ten feet…a good horseman and swordsman, a formidable sorcerer, who had long desired to find a knight in the Christian imperial court who would fight, struggle, and break the spear with him. On several occasions, with the help of his loss of sight and his magic, he slew a total of forty knights, causing such alarm among the imperial people that no one dared to challenge this heathen again.’ The source of the David and Goliath motif could also have been the Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle, known to German chroniclers as well, which describes a similar duel between a Hungarian soldier named Botond in Constantinople.

The appearance of the knightly duel motif in King Henry’s environment provided a good opportunity for the German King to become a regular feature in the German Book of Tournaments of the 16th century. According to these, the King had the first jousting tournament in Magdeburg to commemorate his victory over the Hungarians. Henry’s role in the jousting tournaments can be traced back to the chronicler Widukind’s account of King Henry’s fondness for the games and his personal participation in them, which he describes as having taken place just after the victory at Merseburg/Riade in 933. This had nothing to do with the jousting tournaments that were to develop centuries later, but the medieval historicist approach was not particularly bothered by this. Rasso also made his way into the tournament books, and in Georg Rüxner’s 1530 tournament book, King Henry’s journey after the victory leads first to Mauerkirchen and then from there to Magdeburg.[4] There is a striking coincidence in time between St Ulrich and St Rasso, as the 15th century saw a revival of attention to the saints who interceded for the victory over the Hungarians, a revival in which the approach of the Ottomans was already playing a role.

‘It was his authority that brought Rasso into the world of authentic historical figures’

King Henry may indeed have been recorded in tradition as the victor of the Hungarians, thanks to the Battle of Merseburg/Riade. Yet the memory of the German victories over the Hungarians has been blurred over the centuries, so that in the 15th century, Regensburg sometimes appeared as the site of the battle of Lechfeld near Augsburg, and the city tried to claim the glory of the victory over the Hungarians at the expense of Augsburg. As the Hungarian leaders captured at the Battle of Lechfeld (955) were hanged in Regensburg, the memory of the battle may have remained alive in the city. Even in modern times, the site of the event was called ‘Hunneplatz’, that is, ‘Hun Square’. In the 1280s, the medieval poet of the story of Lohengrin, adapted by Wagner, brought the figure of King Henry into the world of heroic tales, where the king had just marched into Regensburg after his victory over the Hungarians (933). After 1245, Regensburg secured its status as an imperial city once and for all, which provided a good opportunity to embrace and promote the historical sagas associated with the city throughout the century.

Rasso’s figure was also connected to the Hungarians by another thread, since Gertrude, mother of Saint Elizabeth and wife of King Andrew II of Hungary, was a princess of Andechs and Meran. Rasso himself was included in the pantheon of the Andechs–Meran ancestors, and the relics he collected were brought to Andechs, where they were discovered in 1388. The historical records that followed the discovery of the relics also attempted to link his figure more closely to Hungarian history in the context of the ecclesiastical tradition, but this differed significantly from the image of Rasso in secular texts. According to the statues and books, this tradition was originally profane and only gradually expanded to include the ecclesiastical motifs of the legends. It was Aventine who finally sorted out the oral tradition linked to Henrys, which developed in several strands. It was his authority that brought Rasso into the world of authentic historical figures, and his judgment that deprived Hans Dollinger, whom he had described as fictitious, of the same status, even though the two sagas were of similar origin and were enriched in similar ways until the 16th century.

In the German tradition, Bishop Ulrich of Augsburg still plays the role of the heavenly intercessor in the battles against the then still pagan Hungarians. However, he himself could not fight as a priest, so a secular hero was needed, whom popular culture found in the large person of Count Rasso and chivalric culture in Hans Dillinger. While the great German victory of 955 was appropriated by the city of Augsburg and its bishop, Rasso and Dollinger linked the victories of the Henrys in 933 and 948 to the rival city of Regensburg. The legend of Rasso also explained the conversion of the Hungarians to Christianity and the church organization of King Stephen of Hungary, but it is perhaps no coincidence that the name of Saint Rasso remains unknown in Hungary. The legend also reminds us that German victories within a few decades made the Hungarians aware of the need to move closer to the West and Latin Christianity, which was both an opportunity and a promise of the centuries to come.

[1] Charles R Bowlus, The Battle of Lechfeld and Its Aftermath, August 955: The End, Aldershot, 2006, p. 143.

[2] Ernst Meßmer, Graf Rasso. Heerführer Bayerns, Kirchenstifter und Klostergründer von Grafrath, Volksheiliger, St Ottilien, 2003.

[3] Wolfgang Jahn, Christian Lankes, Wolfgang Petz, and Evamaria Brockhoff (eds), Bayern, Ungarn Tausend Jahre, Augsburg, 2001, pp. 94–96.

[4] William Henry Jackson, ‘The Tournament and Chivalry in German Tournament Books of the Sixteenth Century and in the Literary Works of Emperor Maximilian I.’, in Christopher Harper-Bill and Ruth E Harvey (eds), The Ideals and Practice of Medieval Knighthood, Woodbridge, 1986, pp. 50–51.

Related articles: