In the early Horthy era, the Catholic-Protestant contrast was significant, as shown by the example of Dezső Baltazár, the bishop of Tiszántúl, who was considered liberal and “Jewish-friendly” by many. Around a hundred years ago, on 22 January 1921, human excrement was smeared on the chair of Baltazár and on the Book of Psalms lying on it in the Great Church of Debrecen. This scandal proved to be one of the most serious anti-Calvinist offenses of the period and in this two-part article we will explore the main reasons behind this conflict.

In 1920, there were five million Roman Catholics, 1,670,000 Calvinists and 497,000 Lutherans in Hungary, the latter being almost the same as the number of Jews (473,000). In addition, 175,000 Greek Catholics, 51,000 Greek Eastern (Orthodox) and 5,000 Unitarian Christians also lived in the country, not counting the followers of small churches. Throughout its history, Hungary has traditionally been a Catholic country, although Protestantism had a strong social background in Transylvania and the Great Plain (Alföld).

However, with the Treaty of Trianon, the number of Protestants greatly decreased, and the role of the Catholic Church became even more decisive despite the fact that the governor, Miklós Horthy, was a Calvinist.

A ‘rainbow bridge’ should connect Catholic Pannonhalma and Reformed Debrecen

Catholic bishop Ottokár Prohászka used to say that a ‘rainbow bridge’ should connect Catholic Pannonhalma (home of the Benedictines in Hungary) and Reformed Debrecen, and Horthy regularly quoted this in his public speeches during 1920.[1] However, the idea was also criticized by Protestants. Károly Jeszenszky, a Lutheran pastor in Mezőberény, explained that although he would gladly accept Prohászka’s ‘rainbow bridge’, he cannot trust the Catholic side after reading the critical works of Béla Bangha, a Jesuit father, against Protestantism.[2] Kálvinista Szemle (Calvinist Review), with some self-criticism, wrote that there would be no problem with the Catholic Pannonhalma, they miss the ‘old Debrecen’.[3]

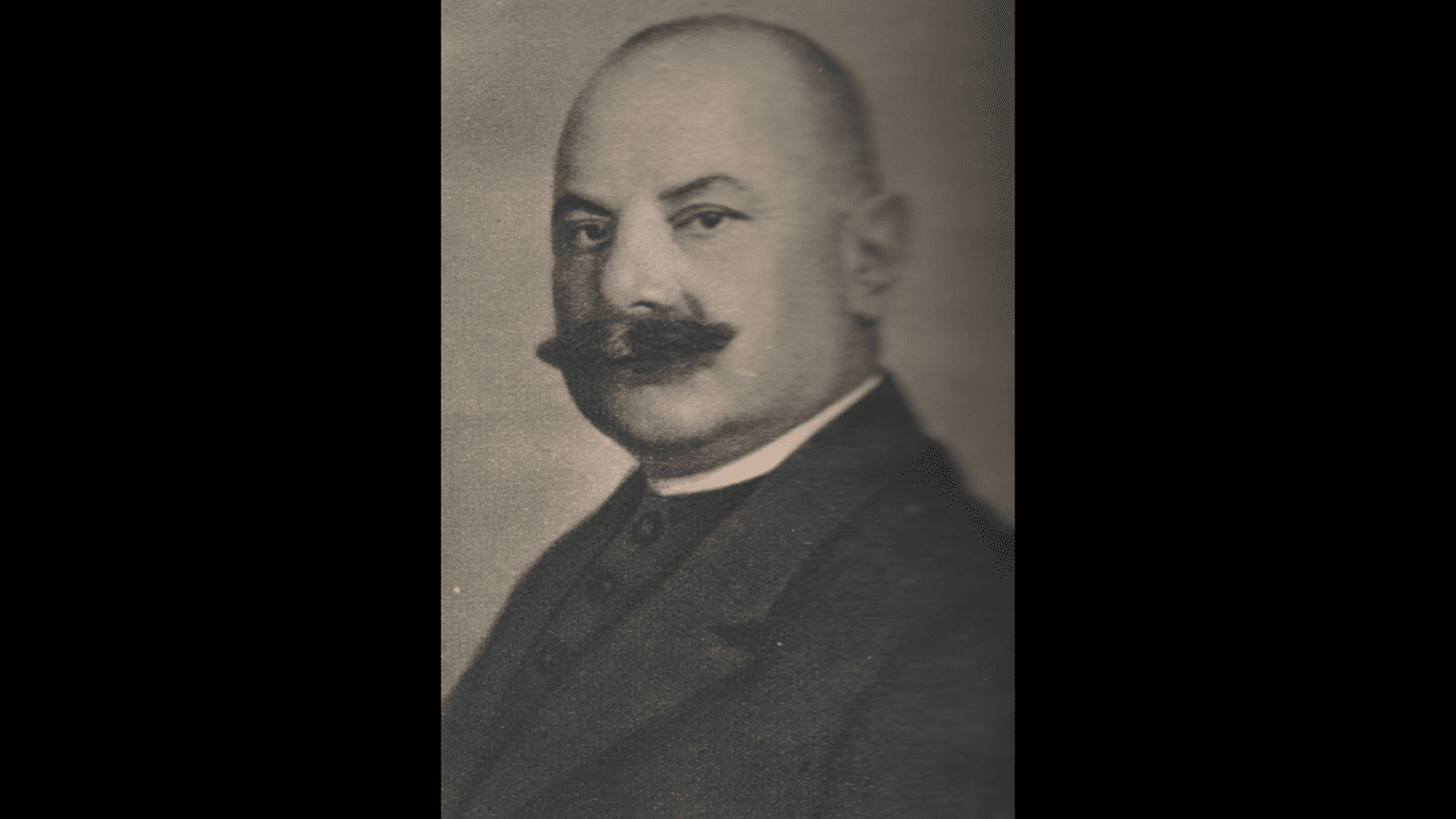

The latter remark points to the internal Calvinist tension, which was primarily generated by the actions of Dezső Baltazár, the bishop of Tiszántúl, who held his position since 1911. Baltazár was not an “ordinary” liberal: he was born into a wealthy family, from the ethnically Hungarian Hajdúság region, and many of his ancestors fought in the revolution of 1848–1849. His athletic figure, tall stature, huge mustache—highlighted by his military-style short hair—and his deep voice were regularly noted in the descriptions of his person.

In one place, Bangha simply called him a ‘Protestant Protestant’, and in his 1936 obituary, Calvinist bishop László Ravasz wrote about him that ‘there was something remaining in him of the virtuous cheerfulness of the old braves. He did not care at all that they feared him, and gladly made them fear him; especially when he noticed that his followers loved him more than his enemies feared him’.[4] He was right in the description: in addition to understanding and acceptance, Baltazár’s character had a large amount of antagonism, even a tendency to insult, and he also bravely stepped into the arena of politics. His philosophy can be known from his correspondence of April 1921, according to which it would be best if Christianity withdrew completely from politics, but as long as Catholicism engages in politics, passivism would be suicide for Protestantism.[5]

His critics repeatedly accused him of greeting the Romanian king at the head of a delegation from Debrecen in Nagykároly after the Romanian invasion – the “accusation” was true, although it should be added that the Catholics, the Lutherans and the Jewish community also greeted the king. ‘A sly peasant from who knows where’, one of his enemies wrote about him. ‘He has been pro-Austrian, democratic, Bolshevik, and even Romanian. In his endless rotation, he did not stop in just one direction, the Hungarian direction’.[6] Among his critics, he was nicknamed “Baltazarescu” and “the Jewish bishop”, but even among Baltazar’s Jewish supporters there was a saying that ‘we have one chief rabbi in Debrecen, and this is Dezső Baltazár’.[7] Baltazár himself compared the situation of the Calvinists—and the Jews—to the biblical “flood” and “hiding in the desert” at the beginning of 1921, and at the end of the year he declared in the Rumbach Street synagogue that ‘we, the Calvinists, and you, the Jews, must unite, to save Hungary’.[8]

Baltazár compared the situation of the Calvinists—and the Jews—to the biblical “flood” and “hiding in the desert” at the beginning of 1921

The Calvinist attitude towards Baltazár was controversial. Bangha also explained in one place that, in his opinion, ‘Protestants in Hungary are split in two directions. One is the direction of the old Hungarian Protestants: they hate everything that is Catholic, and they are friends with the Jews and the Freemasons against us’. He named Bishop Baltazár as the leader of this direction. ‘The others are Protestants in name, they like to work with the Catholics against socialism and atheism, and they more or less openly deny their unity with the Baltazár direction’.[9]

The internal division was reflected in the paper of Jenő Sebestyén, the founding general secretary of the Calvinist Political Association, Kálvinista Szemle. Sebestyén was a supporter of complete territorial revision, social reforms, economic action against the Jews and the representation of Calvinist political interests, and in this sense he functioned as an internal opposition on certain issues. Against Ravasz, for example, the magazine supported the candidacy of István J. Kováts, a Catholic-born Calvinist priest and member of parliament, for the post of bishop of the Danube Region, calling Ravasz, who was otherwise fiercely nationalistic, too liberal. Reformed theologian János Marton urged internal reform in the columns of the Kálvinista Szemle: he wanted to see a ‘more rigid, more closed, harder, more militant’ religion.[10]

In contrast, József Kovács, a Reformed pastor from Kaposszentbenedek, can be cited who wrote in the columns of the Baltazár-aligned National Reformed Pastoral Association’s (ORLE) paper that nationalism and antisemitism dribble down from Budapest into the Reformed Church.[11] In his spring 1921 article, the Calvinist publicist István Milotay suggested to Catholicism to cordon off clericalism (not saying aloud, but meaning Bangha), and to Protestantism to quarantine Baltazár.[12]

It is interesting to note that from all the opinions quoted above, only Milotay’s predictions (or suggestions) proved to be true: as we have already written, Bangha was indeed abandoned by most of his political allies while Baltazár in the end also had to conform to the right-wing interwar system. This story, however, belongs to another article.

[1] Kecskeméti Közlöny, 27 Jan. 1920. 1.; Magyar Jövő, 15 Apr. 1920. 1.

[2] Evangélikusok Lapja, 24 Apr. 1921. 3–4.

[3] Kálvinista Szemle, 25 Apr. 1920.

[4] Baráth Béla Levente: „Földbegyökerezés és égbe fogózás…” A Tiszántúli Református Egyházkerület története Baltazár Dezső püspöki tevékenységének tükrében (1911-1920). Nemzet, egyház, művelődés, X. vol. Sárospatak, 2014, 13.

[5] Hadtörténelmi Levéltár, HM ELN C 1921 50216. Baltazár’s exchange of letters with Jenő Szabó, April 1921.

[6] Lendvai István hagyatéka, Radó András (Debrecen) to Lendvai, December 1920..

[7] Balogh István: Dr. Ecsedi István naplójegyzetei (1920. ápr. 10–1928. febr. 15.) In: A Debreceni Déri Múzeum Évkönyve 1985. Ed. Gazda László. Debrecen, Debreceni Déri Múzeum, 1986, 201.

[8] Baltazár to Lajos Szabolcsi, 12 Jan. 1921. In: Egyenlőség, 22 Jan. 1921. 3.; Egyenlőség, 8 Oct. 1921. 6.

[9] Klestenitz Tibor: Bangha Béla jelentése a budapesti nunciusnak a Központi Sajtóvállalat helyzetéről. Magyar Könyvszemle, 133 (2017). 7-8.

[10] Kálvinista Szemle, 23 Jan. 1921. 1.

[11] Lelkészegyesület, 1920/38.

[12] Magyarság, 27 March 1921. 1.