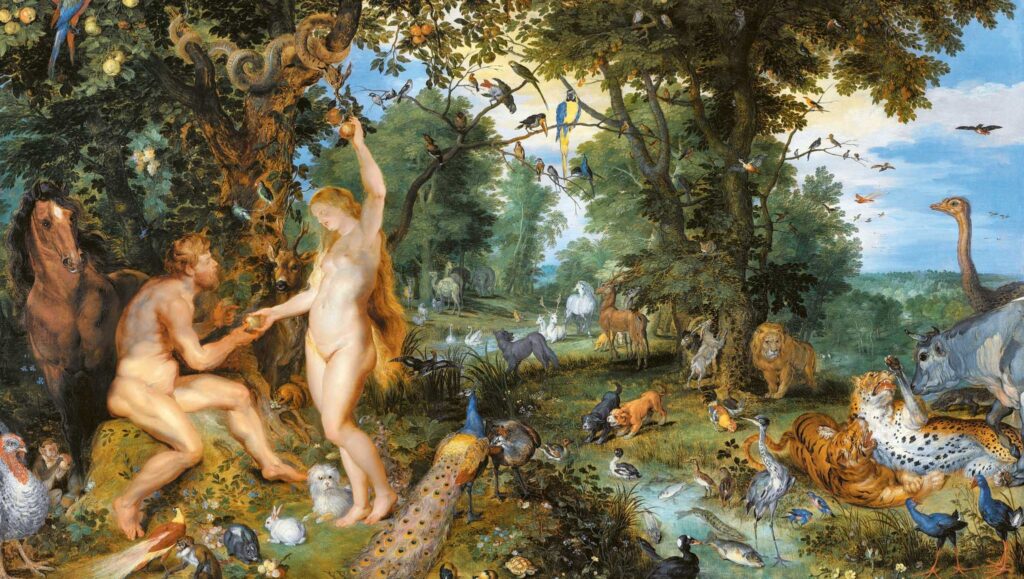

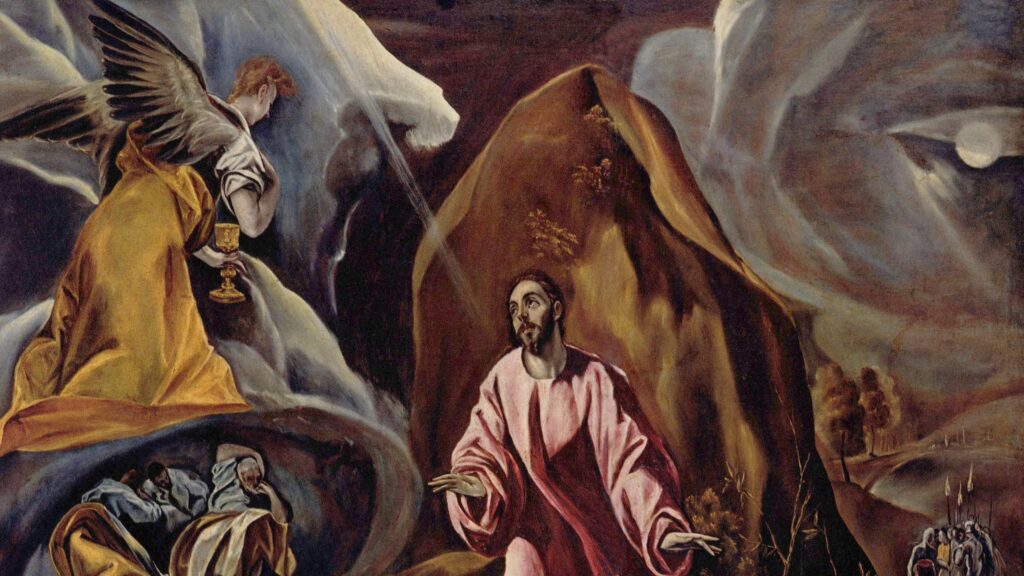

‘This genuine, organic conception of evolution stands in full harmony with a spiritually grounded understanding of the universe. Just as society unfolds its latent traditions, and a seed unfolds the tree inherent within it, so the entire created world unfolds from the infinite possibilities of the Principle.’

‘Time is in fact the hero of the plot…Given so much time, the “impossible” becomes possible, the possible probable, and the probable virtually certain. One has only to wait: time itself performs the miracles.’

‘Modern natural science started from the seemingly noble self-limitation of seeking answers to the question of how the world works, leaving the great questions of why to philosophy and theology. As we can see, this was Darwin’s original objective as well. But did the British naturalist remain faithful to this promise?’

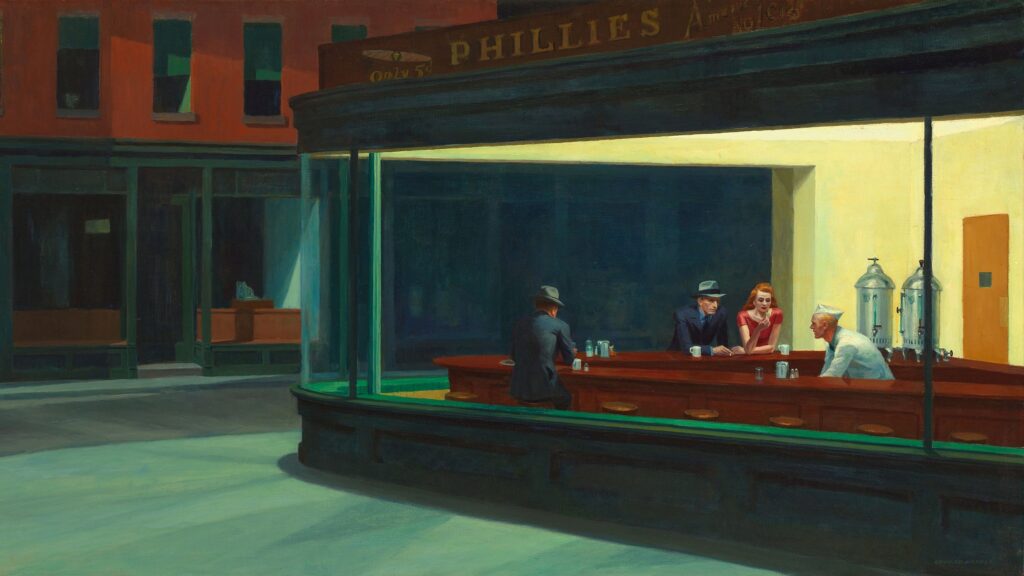

‘The American Republic in the first half of the 19th century gradually drifted away from the Founders’ original vision and embarked on the path of modern mass democracy. The final result of this, paradoxically, became exactly what the Founders had feared…The Jacksonian rejection of the principle of hierarchy led not to the fulfilment of freedom, but to the rise of a new, faceless form of tyranny.’

‘School, therefore, never ends: the modern citizen is the subject of re-education from the cradle to the grave, stripped of the past so that he may obediently march toward the technological utopia.’

‘Since the masses are easily manipulated, democracy is the natural breeding ground for demagogues, and a straight path leads from it to totalitarianism.’

‘After the modern revolutions destroyed traditional, hierarchical structures, the resulting vacuum was filled…by “bureaucratic authority”. The modern state bureaucracy is the political operating system of the Heideggerian Enframing: a rational, impersonal machine which…liquidates all intermediate, organic communities and freedoms in the name of equality and central efficiency.’

‘The moment of birth for the modern myth of progress is when Western thought retained the linear time-scheme of Christianity but radically reinterpreted its content. This “humanist turn” was essentially a process of secularization, during which divine providence was replaced by human reason…’

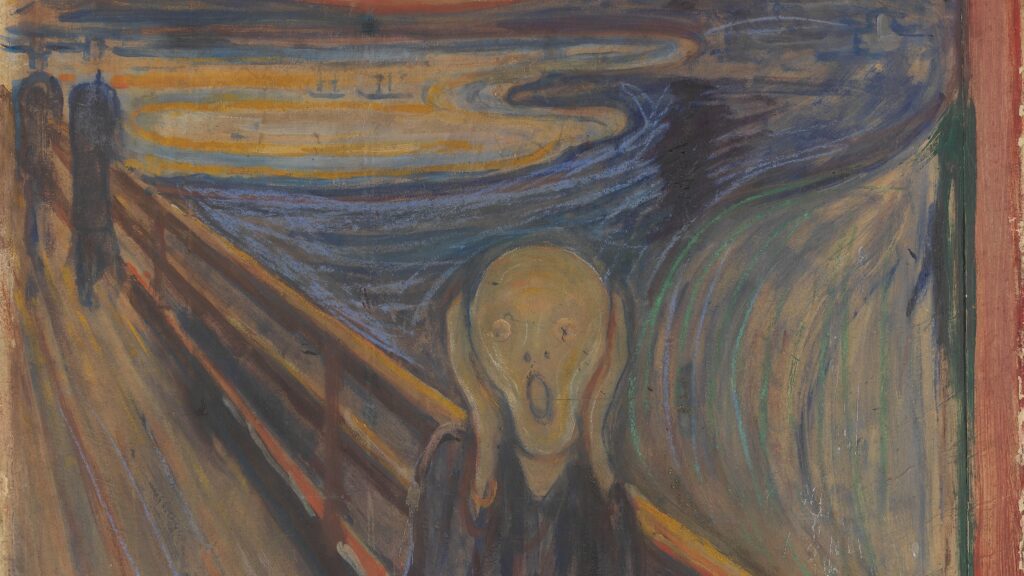

‘The problem is not whether progress has material benefits—it would be foolish to deny them—but that the concept of progress has forced upon us a materialist and quantitative worldview that is incapable of measuring, or even perceiving, what was lost in the process. …Our diagnosis, therefore, is not that progress is heading in the wrong direction, but that “progress” itself is the wrong compass.’

‘Paradoxically, it appears that democracy can only sustain and protect itself from collapse—whether through tyranny or chaos—by relying on elements that are not themselves democratic. It often seems easier to justify democracy with a quasi-mystical hypothesis than with one grounded in the actual conditions of political reality.’

‘It is not an easy task to clean the concept of democracy from the secondary meanings that have been imposed on it during more than two centuries of modern usage. I will not attempt to solve this task; instead, I will undertake a brief interpretation of a very simple principle, the principle of quantity, and its role in modern democracy, in relation to political religion and rationality.’

‘It can no longer be said that the individual manqué is merely a “shadow”; it appears, rather, to be the norm. Today, it is worth reflecting on the extent to which, since Oakeshott’s death, the European experience has shifted from Societas to Universitas—and on the current condition of both the individual and the “mass man”.’

‘The mass man is incapable of making authentic, personal decisions in situations of crisis or autonomy. For this reason, he requires a leader—someone who can think, decide, and act on his behalf. This leader makes the mass man aware of his power through numerical superiority and conformity, shaping modern mass states.’

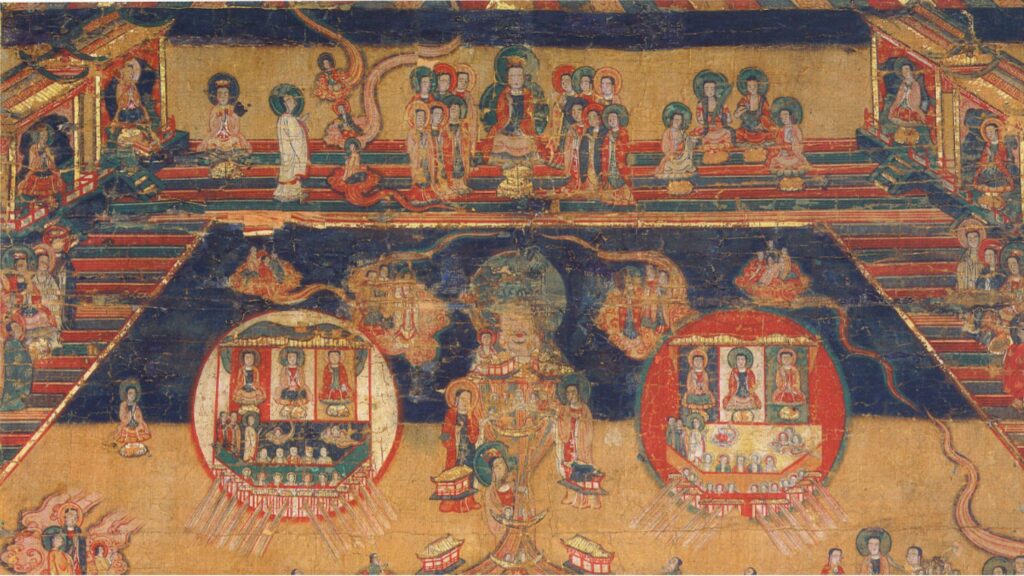

‘…the idea of a Creator conceived and represented in vulgar theological approaches as a quasi-human person is not only unacceptable today but also explicitly harmful to the contemporary expressions and life-opportunities of religion, fostering further denial and turning away in philosophically or scientifically trained minds.’

‘The idea of the survivability of death is a key problem, because in its light the whole of life takes on a completely different meaning: if it is possible, nothing else is more important than this; if it is not possible, nothing else is more important than maximizing power and profit in the short period of life on earth—which submerges all other goals.’

‘According to Prohászka, in modernity the tradition of earlier, non-atheistic ages does not die out completely, so that modernity, despite its distinctness, also draws on expressions of earlier forms of cultural life. If a positive turn is to be made, this must be grasped first and foremost.’

‘Prohászka have perceived that the blaring confidence of progressivist thought reflected only its inner emptiness, its blindness, its superficiality, its logical and philosophical inconsistency. What follows from these “new principles” is, above all, a tragedy of human existence, more serious than ever before. It is the denial of the immortality (or the possibility of immortality) of the soul.’

‘As Márton Molnár puts it, “Prohászka’s work covers three major—closely related—themes: educational science and the history of education…the theoretical issues of the philosophy of culture; and the problems of the modern cultural crisis.” In this paper, we focus on this last area: the modern cultural crisis.’

‘Without culture, Eliot argues, there is no point at all in being human, and it is culture that justifies the content of our existence on Earth for the generations that follow us. “Culture may even be described simply as that which makes life worth living. And it is what justifies other peoples and other generations in saying…that it was worth while for that civilisation to have existed.”’

‘People generally agree that no human society is “without culture”. The concept has been defined in many different ways. The first appearance of the term culture is attributed to Cicero, who used the word in the sense of “cultivation of the soul”…only at the beginning of the 19th century did it acquire the meaning that can be described as “learning and taste, the intellectual side of civilization”.’

‘On our part, we doubt that “history of ideas” as a methodologically coherent discipline existed in Hungary between the two world wars…Nevertheless, their work is undoubtedly a prime example of an attempt at the creation of a conservative-oriented social science. The history of ideas is, in fact, a philosophy of history that takes into account factors that transcend matter, and through a specific research methodology is able to grasp and evaluate the processes that take place “behind” the surface of purely material social phenomena.’

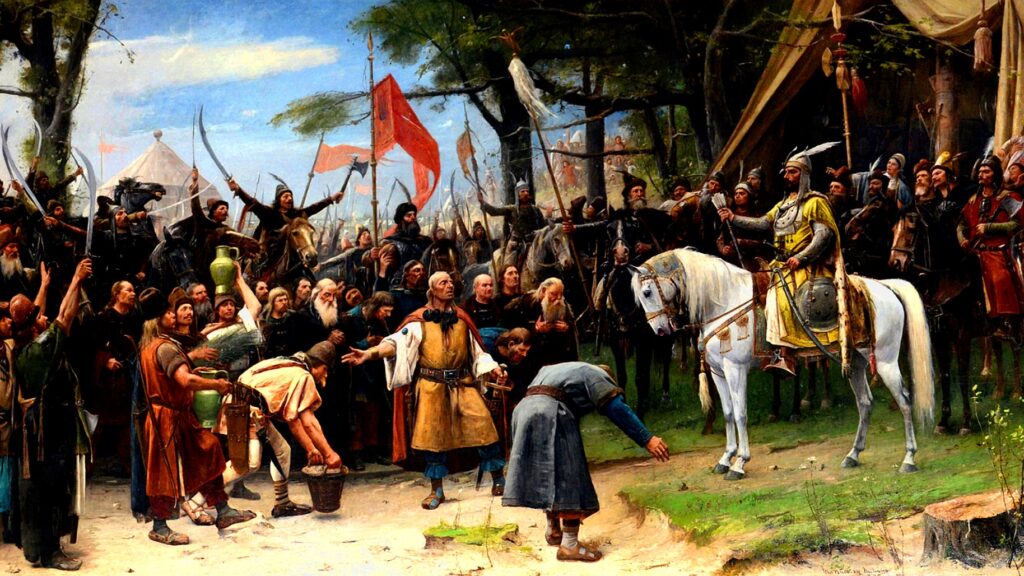

‘Linguistic–ethnic nationalism is the quintessential negative (in Joó’s parlance, “imperialist”) nationalism, a nationalism insensitive to qualitative differences or to more elevated spiritual concepts of the state, such as the unifying “Hungarus consciousness” of the nomadic empire’s supranationalism, which derives from the dynasty’s divinely-derived spiritual unifying power.’

‘The most important distinguishing feature of the Hungarian national ethos and Hungarian nationalism, according to Joó, is that the Hungarian nation’s leitmotif of Steppe origin survived the foundation of the Christian state, and even survived the Middle Ages, synthesizing it with Christianity. In Western Europe, however, a very different kind of nation-building took place. Charlemagne’s brief attempt at empire-building, i.e. his efforts to renew the Roman Empire on a Christian–Germanic basis, essentially quickly failed.’

‘As a committed Protestant, Joó emphasized the primacy of “spirit” over matter in almost all his writings, but he failed to take into account that religion and “spirit” do not always overlap, and religiosity itself simply becomes ineffective if so-called religious people view the world on the same premises as their atheistic and materialistic counterparts.’

‘There can be no question that Thomas Molnar’s thought was often driven by a confrontation with the intensified secularist, materialist, and anti-religious ideological tendencies following the socio-historical and ideological period of the eighteenth century. He sought the roots of modern political philosophies such as liberalism and Marxism.’

‘Today, the expansion of the state apparatus…continues, but is approaching its culmination. In this spirit, that is, the announcement of the ‘‘fourth industrial revolution’’ and ‘‘digitalization’’, all of which fit into the logic of rationalization and rationalism, the world is becoming more and more virtual, and technology is becoming more and more totalitarian, a new mechanism of control.’

‘What can the modern conservative politician do in the face of such a Leviathan, which he did not create? He has two choices: either he retires and no longer wants to be in politics, or he tries to ride this sea serpent, he tries to use the power of the monster to ‘‘take’’ society in a direction that is contrary to the direction of the alleged progress.’

‘If we accept the existence of transcendence as conservatives, we must also accept that everything that is outside the transcendent is sui generis subject to change. Change— and thus clearly also the fact of decline or progress—is made possible by transcendence as everything else ‘‘in’’ the world. The existence of the ‘‘Eternal’’—this is the particular knowledge that is the most important part of the ‘‘wisdom of the ancestors’’ and it is what the moderns have forgotten.’

‘Space and time represent the two archetypes of political existence…Space inherently belongs to the polis, the starting point of political ‘residence’ (at least in the European cultural circle), and time belongs to the ship, the instrument of the ‘free movement of capital and labour’; the ship is an ancient invention but it is also—only developed later in time—a symbol of progression, change and technological dominance.’

‘It is rarely taken into account that forcing a general expansion of education also means levelling. And if something is extended in a general and obligatory way, then it will be quantitative rather than qualitative. If we imagine all of this in a school system that is universally compulsory for everyone, then according to today’s well-known hierarchization of knowledge, only knowledge that can be (easily) validated in the so-called ‘labour market’ will be truly appreciated.’