Romania is in the headlines. Sadly, these are not headlines that anyone in Bucharest will be happy about. In an article published in The Financial Times at the beginning of August, the headline read: ‘Romania risks repeat of collapse with “essential” austerity measures’. ‘9.3 per cent of GDP, Romania’s public deficit was the highest in the EU in 2024,’ the author of the article stated, ‘well above the 3 per cent threshold prescribed in the bloc’s fiscal rules.’

The reality, as I have laid out in a recent paper published with the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs (HIIA), is far worse than either the Western press or the Romanian government would like to acknowledge. When we dig deeply into the data, it appears that Romanians have had their living standards propped up by extensive foreign borrowing. Romania runs an enormous trade deficit—meaning that it floats living standards with enormous imports—and to offset this, it sells government debt to foreigners.

This explains the disconnect between the statistical claims of the IMF and the Romanian government and the realities in Romania. According to the IMF, Romania has higher living standards than Hungary—$49,213 PPP-adjusted per capita GDP in Romania versus $48,600 in Hungary. But anyone who has driven across the Romanian border from Hungary would find these statistics hard to believe. Lived experience—whether in the rural areas or in the major cities—suggests that Romania is substantially poorer than Hungary. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán expressed what anyone with any experience in the region would immediately agree with when he stated last year: ‘Anyone who claims that Romanians are better off than us should move there.’

Romania has been living beyond its means for a very long time. In the run-up to its EU accession in 2007, the country ran enormous trade deficits. Yet these trade deficits were much more sustainable than today. They were propped up with inward investment flows into the country: Foreign Direct Investment or FDI. Therefore, they could be seen as supporting the development of the country. Foreign investment would move in—to build, say, a factory—and the country would import the components needed. When it was finally built, the factory could produce products for export, which would balance Romania’s production and consumption.

‘Romania has been living beyond its means for a very long time’

That is the theory, anyway. But despite these deficits in the 2000s being financed by FDI, Romania experienced a serious financial crisis and entered into a standby agreement with the IMF in 2009. This showed how dangerous trade deficits of the sort being run by Romania could be even with a seemingly stable source of financing. Today, Romania’s trade deficits are financed by the bond markets—a far less stable source of foreign financing. My recent paper with HIIA shows that almost all of the trade deficit is financed through the issuance of Romanian government debt to foreigners.

The problem is that the Romanian government is rapidly losing its fiscal credibility. As The Financial Times article from August acknowledged: ‘all three major rating agencies have downgraded it to just one notch above non-investment grade — or ‘junk status’ — due to the country’s rapidly ballooning debt and high inflation.’ Because of its highly irresponsible borrowing, the Romanian government is facing the real possibility of a fiscal cliff. If the country falls off this cliff, its living standards will be forced back to their real or, as economists say, ‘equilibrium’ level. Romanians will then be forced to realize that the living standards that their politicians—and the Europeans—told them were real were, in fact, fake.

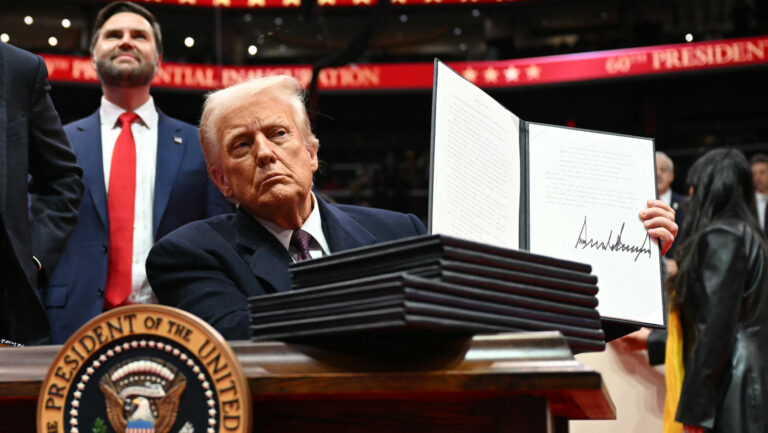

In the past, Romania’s membership in the NATO alliance might have saved it from some of this pain. Before the war in Ukraine, the United States viewed Romania as a key regional ally in case of a war with Russia. The war with Russia is now well-advanced and the Americans have realized that it is unlikely to bleed into the rest of the region. As the war is lost, the United States will start to pull out of the region. In previous years, perhaps Romania could have leveraged its NATO membership for a bailout from the United States—but not today. When Vice President JD Vance criticized Romania at the Munich Security Conference for what he considered anti-democratic practices, the writing should have been on the wall for Romanian leaders.

‘The war in Ukraine has bred a cynicism about violence on the European continent in the Brussels leadership’

Budapest should see this set of circumstances as being highly dangerous. Brussels seems to be far more willing to entertain Romanian nationalists who engage in anti-Hungarian rhetoric than they are willing to entertain figures like Călin Georgescu who was more interested in criticizing the European establishment. The war in Ukraine has bred a cynicism about violence on the European continent in the Brussels leadership. They seem more inclined today to view dangerous strains of ethnic nationalist politics as an opportunity to further their control rather than the destabilizing forces that they obviously are.

For this reason, the best approach for Hungarian politicians is to try to help Romania find a new path. The globalist path that the country has been on for the past two decades is coming to an end. Romania needs to figure out new ways to engage with a new world. The country can no longer rely on external alliances or foreign financial inflows. It must fight for its future and its prosperity. Who is better placed to teach the Romanians how to do this than the Hungarians?

Related articles: