The medieval Hungarian state suffered one of its most serious defeats in the Battle of Mohi on 11 April 1241, where the Mongol army led by Batu Khan destroyed the Hungarian royal army.[1] The army led by King Béla IV of Hungary pursued the Tatar vanguard along the Sajó River in eastern Hungary and set up camp near the village of Mohi, where they intended to defend the bridge crossing the river. Contemporary chronicler Thomas of Split wrote about the events as follows: ‘So around midnight the [Hungarians] came to the bridge; but already a part of the enemy host had crossed over. Seeing them, the Hungarians at once fell upon them. They fought them most bravely and killed a great number of them. Others were driven back to the bridge, forced off and drowned in the river.’[2] However, heroic resistance did not prevent the Mongols from achieving ultimate victory in the end.

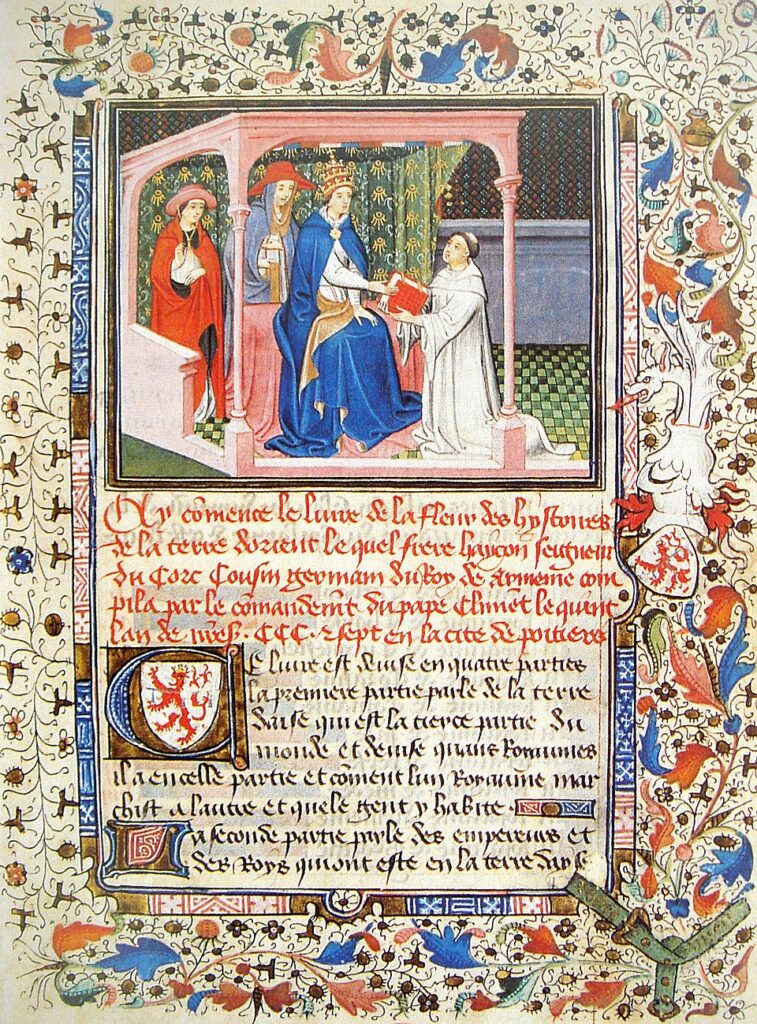

It is no coincidence that studies on the battle and Wikipedia articles illustrate the event with an image of a clash between Mongols and Christians on a bridge. If we take a closer look at the image, we arrive at a slightly different conclusion than before. The miniature comes from the 1309 version of La Fleur des Histoires de la terre d’Orient, a summary of the Tatars written by the Armenian prince Hayton (aka Hethum). This short work on Eastern history became extremely popular in Europe at the time, with 24 French and 32 Latin manuscripts surviving, and it was translated into several languages and had 12 printed editions by the early modern period as well.[3]

‘Heroic resistance did not prevent the Mongols from achieving ultimate victory in the end’

The first book of the four-volume work provides a brief summary of Asian geography and history, the second covers Muslim conquests, and the third presents the history and conquests of the Mongols, including those in Hungary. The fourth book is devoted to the possible alliance between Christians and Mongols and the preparation of another joint ‘crusade’. The undoubted significance of his work is that he was the first Christian author to publish a comprehensive and systematic history of the Mongols from their beginnings to his own time. Surprisingly, Hayton makes no mention of the battles of the Hungarians in his work, referring to Hungary only as a theatre of war. The text accompanying the miniature depicting the bridge does not refer to the Battle of Mohi either, but to the Hungarian–German border and its border river, which the French version refers to as the Danube. Given that the Armenian author did not have access to Western Latin chronicles, his work presents a Mongol interpretation of events.

As the text puts it: ‘After this, the Mongols headed toward the kingdom of Germany until they reached a river which flows through the duchy of Austria. The Mongols planned to cross a bridge at the place, but the duke of Austria and other neighbours fortified the approaches to the bridge, preventing the Mongols from using it. Enraged by this, Batu commanded all to cross and he himself went first into the river…Before reaching the other shore, the horses gave out due to the breadth of the river and the strength of the current. Thus Batu drowned, together with a huge multitude of his followers.’[4] The author was well informed in many respects, as he knew that the Mongols reached Hungary while pursuing the Cumans, and he also mentions that many of the Cumans still live in the country to this day.

It seems that after these events, the Mongols tried to explain why they did not continue their advance westward after 1241–42. However, they could not attribute their failure to the Hungarian king, whom they had defeated and humiliated, and whom, even though, they had been unable to capture. The Austrian prince, Frederick the Quarrelsome, seemed much more suitable for this. In his letters, Frederick indeed attributed much greater glory to himself than he actually deserved, although he was the only one of the western princes to appear armed on Hungarian soil and put smaller Mongol units to flight. No less remarkable is the fact that, according to the text, the Mongol leader Batu lost his life in the battle, which is, of course, impossible, since in the following years he successfully created the framework for what later became the Golden Horde, and did not die until around 1255.

The closest description to this is C de Bridia’s long-disputed travel report, which also mentions a fierce battle that took place at a bridge. In this story, according to the text, Batu, the Mongol leader, was pushed to his death by Prince Kálmán, the brother of the Hungarian king, with his own horse and weapon. If C de Bridia’s text was indeed written in 1247, then this indicates the existence of a very early Mongol tradition. The existence of this supposed Eastern tradition is reinforced by a brief entry in ‘The History of the Patriarchs of the Egyptian Church’, which is incorrectly dated to 1243, stating that ‘a group of Mongols turned toward the lands of the Swabian emperor in Germany. They achieved nothing, and many of the Tatars and Franks lost their lives. The Tatars were defeated, and only a small number of them escaped when they crossed the river.’

‘Based on Eastern sources, it is clear that the Mongols suffered very serious losses in the Battle of Mohi’

Within the next hundred years, Hayton’s work was widely read and copied, including by Giovanni Villani around 1345 and Riccoldo da Montecroce (c 1243–1320), who also identified the river in question as the Danube. In addition, noteworthy due to his connections to King Sigismund of Hungary and the Roman Emperor is the work completed in 1433 by the Milanese humanist Andrea Biglia (d 1435). In it, we can read that King Sigismund himself drew Andrea’s attention to the writing of an Eastern history when the ruler stayed in Siena for a long time in 1432–1433. At first, the king only had him translate Greek letters, then he commissioned him to revise an old handbook, namely Hayton’s work. King Sigismund was not the only one who considered Hayton’s work a valuable handbook. In 1403 Philip II the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, purchased three copies in Paris, and a few years later, in 1413 his son, John the Fearless, also ordered four copies of it.

Given that the clash at the Sajó Bridge is mentioned in Eastern, Persian, and Chinese sources, especially in the biography of the famous general Subutai, it is not unreasonable to think that Hayton’s chronicle contains a distorted, thoroughly misunderstood Eastern account of real historical events. Based on Eastern sources, it is clear that the Mongols suffered very serious losses in the Battle of Mohi, and during the battle, Batu himself considered the possibility of retreat. The Tatars vividly remembered the events of the Hungarian campaign and were still talking about it decades later. This is also confirmed by the descriptions of Western travellers who encountered prisoners of Hungarian origin in the East or saw material relics such as the Hungarian king’s tent, which had been carried off as spoils of war. Several members of the khan’s elite guard also fell in the battle, and Batu even lost one of his commanders, Bakatu. It is quite possible that the memory of serious losses and the death of the Mongol named Bakatu in the fictional story blended with the memory of the rapid and essentially unsuccessful Mongol raids against Austrian territories. The bridge, in reality the bridge over the Sajó River, which according to the fictional story could not be crossed but in reality was captured after fierce fighting, spectacularly concluded and explained the seemingly inexplicable: the failure of the Mongols’ westward advance, which had seemed unstoppable before.

Archaeological research in recent years has confirmed that the ditches surrounding the stone churches on the hills in the middle of Hungary, on the flat Great Plain, which were previously identified as burial ditches, were in fact part of a system of ditches built for defensive purposes. Hundreds of weapons and human remains bearing evidence of battle injuries have been found in them. This shows that the collective resistance of the Hungarians against the Mongols was more significant and played a much greater role in the final outcome of events than previously assumed and than is mentioned in both Western and Eastern written sources. Local peasant communities were able to seriously hinder and slow down the advance of the Mongol war machine with their scattered resistance. Thus, the Kingdom of Hungary defended itself and survived the attack of what was then the largest empire in the world.

‘After the summer of 1241, the West was left with virtually no information coming from Hungary’

Perhaps it is an exaggeration to conclude that the Hungarians lost the Battle of Mohi once more—this time in historiography. The surviving Latin chronicles only tell us about the destruction of the country, and we read almost nothing about the heroic Hungarian resistance, the delaying of the Mongols in Transdanubia, or the series of castles and towns that were successfully defended against the Mongols. In contrast, the Hungarian king is often accused of negligence and sloth. The Hungarian letters sent to the pope in January and February 1242, which do report on the results of the resistance, were not included in the representative Western collections of texts of the time, such as the work of Matthew Paris. The text of an eyewitness, Roger of Torre Maggiore, Archbishop of Split in Dalmatia from 1249, shows no Western European influence either, and Thomas of Split’s report also reached only a few people. Thus, after the summer of 1241, the West was left with virtually no information coming from Hungary, and so the schematic image of a completely destroyed country and a king in exile became established.

The Hungarian chancellery certainly did not recognize its significance, or did not have the energy to send a series of letters to Western courts, from where they could have been included in letter collections. All of this plays a role in the fact that the losses and military failures suffered by the Tatars, most of which occurred in Hungary, are rarely mentioned among the reasons for their unexpected withdrawal from Central Europe. It is not true that Béla IV was unprepared for the attack and chose the wrong strategy in defending the Sajó River line, even if modern works tend to present the battle as one of the greatest strategic blunders. Since Hayton’s best-selling work in Europe attributed the stopping of the Mongols to the Austrian prince, the heroic resistance of the Hungarians was almost completely forgotten. At the same time, Hayton’s work is the one responsible for the only medieval depiction of the battle that preserves certain elements of reality.

[1] Attila Gyucha, Wayne E. Lee, and Zoltán Rózsa, ‘The Mongol Campaign in Hungary, 1241–1242. The Archaeology and History of Nomadic Conquest and Massacre’, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 83, No. 4, 2019, pp. 1001–21.; János, B. Szabó, ‘Hungary, which has lasted for three hundred and fifty years, is destroyed by the Tatar army’, in János B. Szabó and Dorottya Uhrin (eds.), Mongol Invasion Against Europe (1236–1242), Budapest, 2025, pp. 215–46.

[2] Archdeacon Thomas of Split, History of the Bishops of Salona and Split, Mirjana Matijević-Sokol and James Ross Sweeney (eds.), Budapest, New York, pp. 262–65.

[3] László Veszprémy, ‘Sources on the Battle of Muhi – between East and West. Hayton’s Chronicle and Western Historiography’, in Balázs Nagy (ed.), The Mongols in Central Europe: The Profile and Impact of their Thirteenth-Century Invasions, Budapest, 2024, pp. 161–88.

[4] Het’um the Historian’s History of the Tartars, transl. by Robert Bedrosian, Long Branch, New Jersey, 2004, Chapter III: 21. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj /https://ia801209.us.archive.org/32/ items/HetumTheHistoriansFlowerOfHistoriesOfTheEast/Hetum.pdf, accessed on 24 May 2025.

Related articles: