On Sunday, 25 May, Pope Leo XIV, during his Regina Caeli address, recalled the Day of Prayer for the Church in China, celebrated annually on 24 May during the liturgical commemoration of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Help of Christians, who is venerated with great devotion at the Marian Shrine of Sheshan in Shanghai. It was on this day in 2007 that Pope Benedict XVI wrote a letter to the Chinese Catholics, in which he acknowledged their ‘faithfulness to Christ the Lord and to the Church—a faithfulness that [they] have manifested sometimes at the price of grave sufferings.’

‘In the churches and shrines of China and throughout the world, prayers have been raised to God as a sign of concern and affection for Chinese Catholics and their communion with the universal Church,’ Pope Leo XIV said. ‘May the intercession of Mary Most Holy obtain for them and for us the grace to be strong and joyful witnesses of the Gospel, even in the midst of trials, to always promote peace and harmony.’

The Holy Father had also made reference to another event that took place the day prior, the beatification of Father Stanisław Streich, a Polish diocesan priest who was killed for the Catholic faith in 1938 ‘because his work on behalf of the poor and of workers annoyed [and]…displeased the followers of communist ideology.’ The Pontiff expressed his hope that the example of Blessed Stanisław Streich would ‘inspire priests in particular to spend themselves generously for the Gospel and for their brothers and sisters.’ This is exactly what the late Roman Catholic Bishop of Shanghai and the Apostolic Administrator of Suzhou and Nanking, Cardinal Ignatius Kung Pin-Mei, did.

Born in 1901 into a Shanghai family with Catholic roots spreading back at least five generations, Kung was ordained a priest in 1930 and consecrated a bishop in 1949. Simultaneously, he became the first native Chinese Bishop of Shanghai, just after the communists took control over China under Mao Zedong, whose totalitarian rule resulted in a vast number of deaths, with tens of millions of victims of famine, political persecution, prison labor, and executions.

In 1951, somewhere between 100,000 (the official number) and 1,000,000 (the unofficial number) men, women, and children in China were killed in front of cheering crowds for the crime of being Catholics or ‘imperialists’. Clergy were bullied, tortured, and arrested on trumped-up charges. The CCP clearly hoped to eliminate all Christian leaders so that it could ‘re-educate’ the laity to their new religion: Communist ideology.

‘The CCP clearly hoped to eliminate all Christian leaders so that it could “re-educate” the laity to their new religion: Communist ideology’

Kung was created a cardinal in pectore—Latin for ‘in the chest’ or ‘in the heart’, a term used in the Catholic Church for an action, decision, or document which is meant to be kept secret—on 30 June 1979, when he was serving a life sentence in isolation in China. Living ‘in the heart’ (in pectore) of Pope John Paul II for 12 years, Cardinal Kung was publicly proclaimed a cardinal on 28 June 1991.

The story of Cardinal Kung is that of a faithful shepherd—a saintly figure who refused to renounce God and His Church, despite the consequences of a life sentence imposed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Three months before his arrest in 1955, then-Bishop Kung stood by his clergy and the faithful in China, rejecting numerous offers of safe passage out of the country. His courageous stand inspired millions of his countrymen to follow his example of fidelity to the Roman Catholic Church. Anticipating the imminent arrests, Bishop Kung trained hundreds of catechists to preserve and pass on the Roman Catholic faith to future generations in his diocese. The heroic efforts of these catechists, their martyrdom, and that of many faithful and clergy contributed to the vibrant ‘underground Church’ in China of today.

As explained in a previous article, the underground Church is different from the Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA), which was established by the CCP in 1957. By early 1958, the first Catholic bishops were illicitly appointed by the CCP without reference to the Holy See, the universal government of the Church. In June 1958, Pope Pius XII issued his encyclical Ad Apostolorum Principis in which he condemned China’s ‘parallel’ church by refusing to recognize any episcopal consecrations performed without prior Vatican approval. Numerous priests, nuns, and faithful were imprisoned, tortured, and even put to death for their refusal to submit to the CCP’s institutional church.

On 8 September 1955, Bishop Kung, along with more than 200 priests and Church leaders in Shanghai, were arrested. He was accused of collaborating in ‘a scheme of U.S. imperialists and the Vatican to subvert the Chinese people’s democratic regime’. In truth, his crime was his refusal to participate in a schismatic act, that is, his refusal to agree to be a leader of a false church in China, one that obeyed the CCP, not the pope.

Months later, he was taken out to a mob ‘struggle session’ in the old Dog Racing stadium in Shanghai, where, with his hands tied behind his back, wearing a Chinese pajama suit, Bishop Kung was pushed forward to the microphone to confess to the allegation. To the shock of the security police, they heard a righteous loud cry: ‘Long live Christ the King! Long live the Pope!’

The crowd responded immediately: ‘Long live Christ the King! Long live Bishop Kung!’He was immediately dragged away by the police and disappeared from the world until he was brought to trial in 1960, when he was sentenced to life imprisonment. He suffered inhuman living conditions and mistreatment that were common in Communist prisons. He died on 12 March 2000.

The night before he was brought to trial, the Chief Prosecutor asked once again for his cooperation to lead the independent church movement and to establish the Chinese Patriotic Association. His answer was: ‘I am a Roman Catholic Bishop. If I denounce the Holy Father, not only would I not be a Bishop, I would not even be a Catholic. You can cut off my head, but you can never take away my duties.’

‘You can cut off my head, but you can never take away my duties’

Bishop Kung vanished behind bars for 30 years. During that time, he spent many long periods in isolation, being denied the right to receive visitors, including his relatives, letters, or money to buy essentials, which were rights of other prisoners.

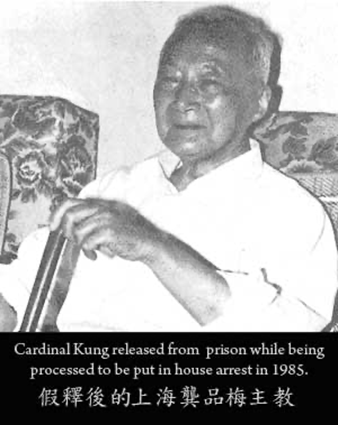

Kung was released in 1986, though he was kept under house arrest until 1988, despite the efforts of his family to permit him to leave China. Under the escort of his nephew Joseph Kung, he was permitted to leave China for medical reasons and settled in the United States. He died in 2000 at the age of 98 from stomach cancer.

Cardinal Kung, like Blessed Stanisław, is someone who should be raised to the altars of the Church. The Vatican’s clandestine agreement with the CCP, which seeks unity with the CPA—just the opposite of how Kung lived his life—may be one of the factors delaying his beatification process. Let us pray that the life of this faithful shepherd, who inspired the lives of millions of persecuted Christians and continues to do so, will be officially acknowledged by the Church.

‘If we renounce our faith,’ Cardinal Kung once said, ‘we will disappear and there will not be a resurrection. If we are faithful, we will still disappear, but there will be a resurrection.’

Related articles: