On 7 October Hamas carried out the world’s third-deadliest terrorist attack, targeting the Israeli side of the Gaza Strip border. Approximately 1,200 people—mostly Jewish civilians, along with soldiers—were killed with shocking and brutal violence, and around 250 Israelis were taken hostage. The surprise, multi-front, and meticulously planned operation was clearly intended to make history for Hamas: to instil fear among Jews, deliver an unprecedented blow to Israel, and demonstrate the vulnerability of the Jewish state.

The Hamas operation became a quintessence of terrorist attacks: if the definition of terror is ‘the use of overt violence to instil fear’, then this was it. The radical Palestinian organization had achieved its goal. The death squads, who partially broadcast the atrocities live using GoPro cameras, gained instant and maximum publicity for the series of attacks. Hamas, in effect, proclaimed to the world that Israel could be defeated.

‘If the definition of terror is “the use of overt violence to install fear”, then this was it’

On the morning of 7 October the Jewish state became dysfunctional for a few hours, and Israeli society was forced to experience for the first time since the state’s founding in 1948 what it was like when the army did not protect the population. The trauma of the Holocaust was that the Jewish people became utterly vulnerable, even in what should have been their own homeland, all the way to the death camps. The trauma of October 7 is that, 80 years later, it happened again—this time in the land of the Jews: no one protected them from being massacred.

The Great National Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

During our week-long tour of Israel, we did not meet a single Israeli who thought otherwise. Israeli society is living in a great, collective post-traumatic stress—Hamas not only took human lives, bringing grief to the lives of tens of thousands of relatives, acquaintances, and neighbours, but also wounded the souls of millions of Israelis. Each of our interviewees recalled how they learned about the events that morning and how they were overcome by paralyzing terror: in a few minutes, gunmen on motorcycles might show up at their doorstep to kill them.

The Israeli psyche was scarred that morning: they were not safe. Despite military superiority, checkpoints, fortified positions, the Iron Dome, security walls, widespread firearm ownership, and the proximity of the IDF, Hamas found a gap in the security system and inflicted immense pain and damage. On 7 October, the myth of Israel’s inviolability collapsed—shaking the very foundation on which the modern Jewish state, established in 1948, was built.

What is psychologically true on an individual level is also true on a national level: the victim struggles to process the aggressor’s actions, to grasp the serious harm he has suffered, and to forgive himself for how he ended up in trouble. Israel has been in ‘trouble’ ever since the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob laid claim to the ‘promised land’. All of Jewish history revolves around taking on ‘trouble’ and interpreting it—and the national and eschatological purpose of the Jewish people stems from their attachment to this land (eretz).

‘The myth of Israel’s inviolability collapsed, and the new Jewish state of 1948 was built on this foundation’

However, Hamas—the Palestinian organization that fights against what it sees as the Jewish occupation of ancient Muslim lands through armed force—does not tolerate Israel’s very presence. In its founding charter, it declares the goal of liberating these territories, which, according to its ideology, can be achieved by eliminating the ‘Zionist entity,’ that is, the state of Israel, based on the ‘from the river to the sea’ doctrine.

Patriotism — Re-Buttoning identity

Following the initial shock, self-defence activity and the patriotic spirit intensified among Israelis, parallel to the re-experience of vulnerability. Tens of thousands volunteered and donated to community programmes aimed at restoring destroyed settlements.

‘After October 7, there was an unprecedented unity. In addition to the existing Jewish identity, the Israeli identity—the sense of national belonging—was strengthened among people,’ Ronni Shaked, a researcher on Middle East and Palestinian affairs at the Truman Institute of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, explained to our paper in a restaurant in Jaffa. According to the veteran expert, every nation has its own origin myth. For Judaism, this is a sense of mission based on being chosen by God—but in times of crisis, these myths can significantly lose their sustaining power.

Shaked added that even in such an extreme situation—after the terrorist attack that shook the entire nation—the identity of Israelis has not been shaken. However, there are shifts in their mentality that had been solidified over previous decades: Israelis trust their elected governments less and less, but their nation more and more. The university professor also pointed out that Israel lives under constant existential threat. In Tehran, for example, a countdown clock on a downtown street shows how much time remains until Israel is destroyed, reflecting the Iranian ayatollah regime’s expectation that the Jewish state will be eliminated by 2040.

‘In addition to the existing Jewish identity, the Israeli identity—the sense of national belonging—was strengthened among people’

When asked whether there is still a chance for a two-state solution, Shaked replied that it remains Israel’s strategic interest. The alternative—a one-state solution—would make it impossible to maintain a democratic Jewish state. With a growing internal Palestinian population, Israel could no longer remain a Jewish nation-state, and control would eventually slip from Jewish hands, as the government’s Jewish majority could be endangered. According to the expert, Israel will also have to overcome another fundamental strategic obstacle in the future: it must truly become part of the Middle East, not merely exist within it.

Trust Is Lost

On the edge of the Jewish settlement of Pedu’el in the West Bank, at the so-called ‘Israel’s Lookout’—from where you can see the western part of Israel all the way to Tel Aviv and the Mediterranean Sea—we mingled with settler wives resting at the local buffet, rocking their babies. One of them had Hungarian ancestry, and as soon as she learned we were Hungarians, she became talkative. She explained that she came from the nearby Israeli city of Petah Tikva and settled here with her husband and now four children, drawn partly by the eretz, and partly by the hope of a better life and the benefits of ‘rural’ living. Of course, life in the settlement carries different security risks than in the city—two weeks before our visit, Palestinian assailants shot at a family on the access road to the neighbouring Bruchin settlement, killing Tzeela Gez, a woman on her way to give birth. Tragically, her baby boy, delivered by caesarean section, died two weeks later.

The life of Jewish settlers in the West Bank is unique: they organize their everyday lives while being wedged among the Palestinian Arab population, so the management and logistics of matters that are taken for granted elsewhere require special attention and preparation. When traveling between settlements, we also had to transfer to an armoured bus, which is standard procedure.

However, 7 October brought a radical change even in the lives of the Jewish settlers. As the Jewish woman who spoke to us said, in the hours of the terrorist attack, they were also convinced that Hamas units would appear in the Jewish areas of the West Bank at the same time as the Gaza operation, thus putting the lives of the settlers in immediate danger.

This did not happen, but everyday life was radically changed by the events. In previous years, it was common for Palestinian workers to work as cleaners, gardeners, and babysitters at the homes of Jewish settlers, and in many cases they could even be their neighbours—after the terrorist attack, however, all trust evaporated between the Jewish and Arab populations, and the settlers no longer dared to allow Palestinian employees into their homes. The only points of contact remained the large, multinational or Israeli factories and plants, and due to the labour shortage, these enterprises continued to employ Arab workers. Otherwise, however, the ‘iron curtain’ had completely descended between the two nations.

How Did Everything Change on 7 October?

It’s a terrible feeling to drive to the former site of the Nova festival. Everyone in the minibus falls silent as you approach, but an equally eerie silence surrounds you as you step outside. We’ve all seen the horrific images of the carnage that took place here, as Hamas gunmen hunted down Jewish youths fleeing in panic during the surprise attack.

You stand on the sandy area in front of the former ‘main stage’, which was the venue for the party on the night of 6 October, but where the ground beneath your feet soaked up the blood of 378 Israelis at dawn the next day. Everything comes alive—partly because during our one-hour stay, Israeli tank batteries sounded several times and military drones buzzed overhead. Hearing the noise of the open-air event near the Re’im kibbutz, the attackers arrived on motorbikes from the southwest (the Gaza border is only five kilometres away). Chaos broke out in the parking lots as people tried to flee: most festival-goers ran east toward a bushy area, but there are no large landmarks here that could have hidden the thousands of Israelis.

Almost without exception, the survivors of the horror are undergoing psychiatric treatment. Many later committed suicide under the burden of their recent past, while others struggle with depression. Increasingly, some—partly for therapeutic reasons and partly to honour the memory of their comrades—commit to regularly sharing their stories with the visitors who come to commemorate.

‘Eerie silence surrounds you as you step outside at the former site of the Nova festival’

Mazal Tazazo is one such survivor. We met the young Israeli woman of Ethiopian origin at the place where she stood in front of the tent at dawn during the attack and faced the inevitable. She arrived at the Nova festival with two friends, and according to her, the party had an euphoric, unforgettable atmosphere. However, at half past six in the morning, security stopped the music and nervously called on the partygoers to leave the area immediately. Mazal and her friends wanted to drive, but by then there was a traffic jam between the parking lot and the main road, and they couldn’t get out because their car got stuck on the bumpy terrain. So they ran to the access road, where they had to face the tragic reality: they were met by a hail of bullets from the direction of Re’im, so they tried to escape in the opposite direction, crawling under the cover of the stuck and abandoned cars.

By the time they reached the bush, they realized that the terrorists had almost surrounded them. They tried to hide but were found and shot at. Mazal was hit in the hand by a bullet and struck in the back of the head with a rifle butt. She pretended to be dead, and only thanks to her incredible presence of mind did she survive—but her two friends were shot dead beside her. However, the ordeal was not over. A few hours later, the escape route was also closed, and the gunmen set fire to the bush. She could only break out, together with other survivors lying nearby, toward the terrorists raiding the road. Mazal recklessly ran to an abandoned car and, huddling on the floor of the back seat, hid under a blanket. The Hamas gunmen crawled around her for a long time but did not see her. She was rescued by emergency responders who arrived at the scene in the early afternoon and was immediately taken to the hospital.

‘She pretended to be dead, and only thanks to her incredible presence of mind did she survive’

Mazal told her story with a blank expression, flinching only once when, halfway through the conversation, an Israeli tank battery roared again. After the soft-spoken, worn-out young woman, we met an angry man in his late 60s at the other site of the massacre, in the neighbouring Be’eri kibbutz. Danny Majzner did not hide his frustration that the Israeli government and army had been unable to prevent the disaster.

‘The government has failed us,’ he stated unsolicited, then added: Kibbutz Be’eri was founded in 1946, before the state of Israel was declared, and the Israeli government promised maximum protection to the border kibbutzim in exchange for maintaining Jewish life in unsafe areas—a ‘contract’ he believes the Jerusalem leadership has violated.

As a result of 7 October, the man shifted from being a centre-left person to a centre-right voter, abandoning his moderate stance on the Palestinian issue and supporting the displacement of the Palestinians. However, he no longer sees this as feasible under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu, but rather with the New Right party and its leader, Naftali Bennett. ‘There can be no coexistence here, it’s either us or them,’ explained Mr Majzner, who first came to Israel from Australia in 1968 and settled here permanently in 1991, in relation to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

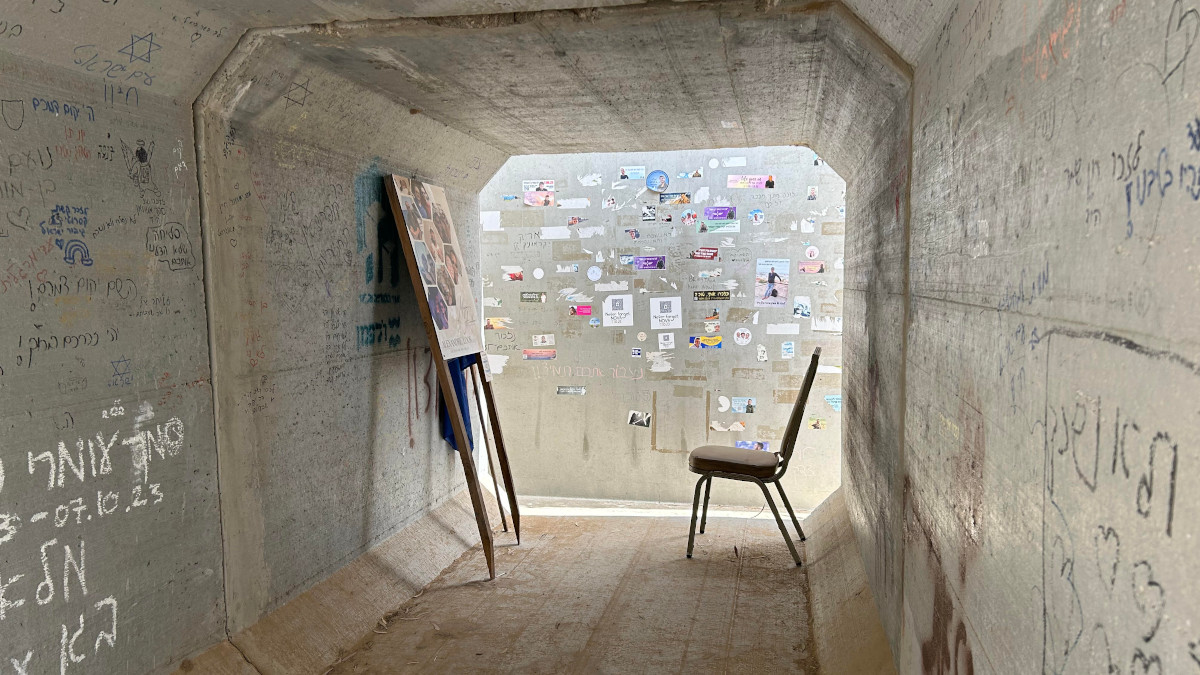

He has reason to be angry: his sister was also killed by Hamas militants on the kibbutz’s territory, and he himself owes his life to the fact that his house had a safe room upstairs to protect against rocket attacks, which the Hamas militants did not notice—he spent 20 hours inside, starving and thirsty, in the dark, before the terrorists left the half-destroyed settlement.

Kibbutz Be’eri was stormed by around 350 gunmen in the early morning of 7 October—an average of 15 Israeli soldiers secured the settlement, so the defence against such superior forces was hopeless. In the settlement of 1,100 people, the terrorists massacred 106 residents, and 140 of the 320 houses were destroyed, making them uninhabitable.

‘He has reason to be angry: his sister was also killed by Hamas militants on the kibbutz’s territory’

The most destroyed north-western quarter of the kibbutz has since been left untouched by the locals as a shocking memento for posterity: the doors of the houses once inhabited by families, children, and the elderly stand wide open; toys lie scattered in the yard; clothes remain on the couch; documents are left on the table; and objects of former life are still there—only their users are no longer present. It is a poignant visit, and according to plans, the place will remain as it is, to be turned into a museum so that future generations will never forget the tragedy. In addition to the remaining 50 or so residents, hundreds of settlers are expected: a new wing of the kibbutz is already under construction, with 150 houses being built for them, so that not only the past but also the future can continue in Be’eri.

The New Status Quo: Israel Is Even Stronger

The perception of security is therefore poor, but the security situation itself has changed significantly in the Jewish state’s favour. Israel responded quickly and forcefully to the Hamas attack that humiliated its army and security services, immediately regained the initiative, and used the forced situation—which was not of its own choosing—to change the regional status quo, no longer advantageous to it, by military force.

On the western front, it liquidated the leadership and destroyed the military infrastructure of Hamas, and it did the same on the northern front to Hezbollah. It used the transitional period between the fall of the Assad regime and the establishment of the new Syrian government to expand the demilitarized zone on the Golan Heights, and with the weakening of the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority, it is increasingly controlling the situation in the West Bank with military force, while it is suppressing the attacks of the Yemeni Houthi militias with its missile defence system. By repelling the proxies, the influence of its main enemy, Iran, has also been significantly weakened in the region.

Israel has won the multi-front war that has been going on for a year and a half, emerging stronger, while putting its opponents at a strategic disadvantage on all fronts.

We saw the improvement in the security situation with our own eyes in two dangerous border areas. We travelled to Israel’s northernmost settlement, Metula, which six months ago was regularly shelled by Hezbollah from across the Lebanese border, located just one kilometre away. The settlement is indefensible, surrounded by Lebanese territory on three sides and by hills, and most of the Jewish population had to be evacuated during the war for security reasons.

Last fall, the IDF invaded the Lebanese part of the border region and eliminated Hezbollah positions, then set up five military posts on the Lebanese mountaintops around Metula. Since then, the town has not been hit by an airstrike, and the Israeli army immediately fires on any military movement in the demilitarized zone, explained Sarit Zehavi to us at the lookout point called Mitzpe Dado, next to the military base above the town. The founding president of the Alma Research and Education Center lived through the rocket attacks on northern Israel just a few kilometres away, but she is part of the minority who stayed here—70–80 per cent of the population of Metula and the surrounding villages did not return.

The trauma is still very fresh. The people who once lived here have left their properties behind and no longer trust that peaceful life can return to the region. Since the ceasefire agreement was signed in late November, the IDF has carried out around 400 attacks on Hezbollah; even the slightest violation of the ceasefire is immediately punished by them.

‘Metula is indefensible, surrounded by Lebanese territory on three sides and by hills’

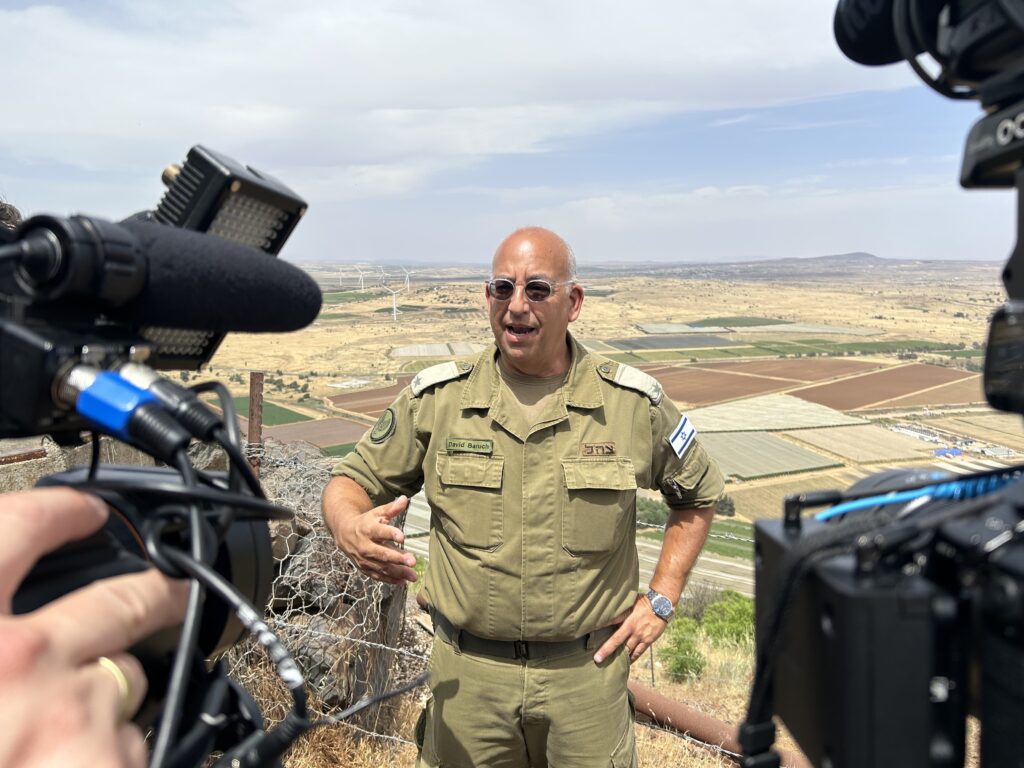

The other border area we reached in our minibus was Bental Hill, in the Israeli-controlled part of the Golan Heights, just two kilometres from the demilitarized zone established between Syria and Israel. Here we met the spokesman for the local IDF force, David Baruch, who showed us in every direction the changes in the border lines.

The western part of the Golan Heights is a valley that is difficult to defend, so Israel occupied the Bental Mountain region, the heights, in order to protect the northern part of the country above the Sea of Galilee and the western areas of the Golan.

‘Hamas is not only a terrorist organization, but also an ideology, and you can’t fight an ideology with weapons alone’

During the turbulent weeks of the attempted overthrow of the Syrian regime at the end of last year, the IDF bombed and temporarily occupied several border posts abandoned by Syrian government forces. ‘Temporarily’ means that Israel does not claim these areas but controls them for security reasons. Among these, the most strategically important are the high-altitude positions on Mount Hermon, as all Syrian troop movements in the valley eastward towards Damascus can be closely monitored from there, the spokesman added.

‘Hamas is not only a terrorist organization, but also an ideology, and you can’t fight an ideology with weapons alone,’ David Baruch told our newspaper, adding that he believes that Hamas can nevertheless be broken, and Israel’s original war goal, the elimination of Hamas, is therefore achievable. As every Israeli decision-maker we had the opportunity to speak to in a week said: first, the Israeli hostages must be freed at any cost; but then Hamas must be destroyed with full force and military means so that it can no longer pose any threat to the Jewish state. In other words, the war will continue, one way or another.

Related articles: