There are many today who believe that the United Nations Organization (UN), after it had adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948—originally declared as The Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man—is still an NGO that works towards humanity’s well-being. Globalists highlighted it when amidst the declared COVID-19 pandemic UN Secretary-General António Guterres launched a Comprehensive Response to COVID-19 last year with the self-proclaimed aim of ensuring that the world economy and the people emerge stronger from the crisis. Yet behind the façade of Article 1 of the UDHR, which says ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’, the UN has unmasked its subtle global agenda, as with its pro-LGTB+ or Agenda 21 policies that have reclassified the human person into a mere individual statistic expendable to the whim of technocrats. To achieve this, the UN has imposed so-called effective altruist guidelines and codes of conduct upon nation-states as soft law.

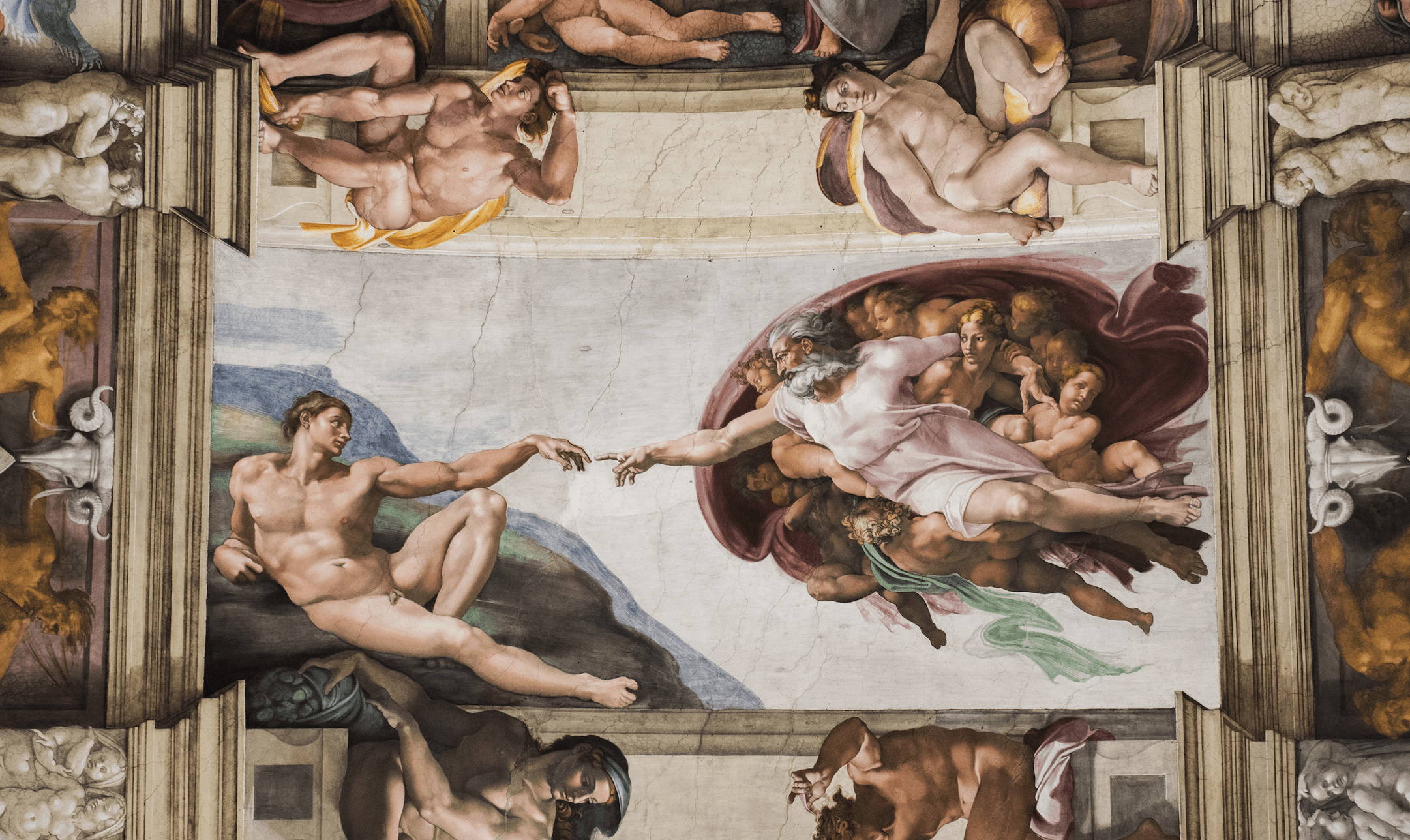

The person is no longer considered as a social being created in the image and likeness of God. Rather, he or she has been categorised as an individual whose subjective wants, whatever they may be, are to be satisfied at all costs, regardless of whether or not the principles of the natural order of things are observed.

While the terms individual and person are synonymous and interchangeable, they communicate different aspects: a personis a created human being with a soul, capable of reasoning by himself, whereas an individual in the modern world is seen as existing only as part of a group of corporation.

The concept of individualism is a common one in American democracy as highlighted in the Declaration of Independence whereits principal author, Thomas Jefferson, emphasised the natural rights of ‘Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.’ Jefferson, however, like the rest of the American Founding Fathers, recognised that the inalienable rights man has been endowed with by the Creator are in order for us human beings to live out our God-given individual freedom.

This is because, as John Locke wrote in his Second Treatise on Government:

‘[A]ll men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of Nature, without asking leave or depending upon the will of any other man.’

Paradoxically, the present-day misconstrued idea of secular individualism, which was fully developed during the Enlightenment, has its roots in early Christianity.

Christian Anthropology of the Human Individual

The erroneous notion of individualism in the Christian West can perhaps be traced back to Marcion of Sinope (84/5 – 160 AD). In his Antithesis (Contradictions), Marcion taught that the all-loving God as revealed by Jesus Christ was the only and true Supreme Being, different from the jealous and malevolent Hebrew God of the Old Testament. He both rejected the Hebrew Bible and proclaimed that Yahweh (the Jewish god) was a lesser demiurge who had created the earth, and whose law, i.e., the Mosaic law that called for the stoning of women caught in adultery, or said ‘An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth,’—something Jesus Christ refuted and abolished; the former by forgiving the adulteress in the Gospel of John and the latter by saying ‘turn the other cheek’— represented bare natural justice and was incompatible with the love of God.

Marcion, consequently, dwelt on the universal salvation of Christ as presented by St. Paul and on man’s abstract individualism, inherent in the conception of a new covenant with this loving God. In his view, the new covenant was a pact in which the individual was free from any discipline or obligations as found in the Hebrew Scriptures, therefore highlighted the fate of the individual soul at the cost of the community of saints. This idea would inadvertently be evolved by Martin Luther.

The modern notion of individualism, as Oliver O’Donovan and Joan Lockwood O’Donovan explain in their publication From Irenaeus to Grotius, can nevertheless be traced back to Christian philosophers, such as the Dominican Friar John of Paris (1255 – 1306) who diligently distinguished between the approach to proprietorship of ecclesiastical and civil governments. John of Paris, like some of his contemporaries, focused on the primacy of private ownership in the civil order, as opposed to common ownership in the ecclesiastical order. While the individual essentially became the proprietor of his own personhood, this did not mean he no longer owed anything to society, let alone dispensed himself from the divine mandates as revealed in Holy Writ.

By the 14th and 15th centuries, individualism was in one way or another linked to the spiritual Church

By the 14th and 15th centuries, individualism was in one way or another linked to the spiritual Church. A case in point was the defence before the papacy of the use of temporal goods by those who professed a vow of poverty despite the fact that they did not own anything. In his repudiation of papal absoluteness, the Franciscan William of Ockham (1285 – 1347), ‘wrote of liberties as well as rights, “granted to mortals by God and nature”, and most importantly, incorporated these liberties into his concept of Christian freedom, understood not only as emancipation from the burdens of the Mosaic Law and from sin, but also as original individual powers and action.’[1]

This was further developed by the Conciliarist Jean Charlier de Gerson (1363 – 1429), who upheld the individual’s natural right to appropriate the necessities of life, which can never be forfeited. Hence, when the Protestant Reformation came on the scene during the sixteenth century, the focus on the individual and his natural rights was already well-established.

The theological doctrine of justification of the father of Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther (1483 – 1546) further contributed to the idea of the human person as an individual. For Luther, the sinner could only be redeemed by accepting the grace of Christ and not through good works or use of the Catholic Church’s sacraments.

As a former Augustinian monk, Luther expanded on Augustine’s City of God, the earthly and heavenly kingdoms by holding that God ordained two kingdoms or two realms in which humanity is destined to live. The earthly kingdom is of creation, of natural and civil life, in which a person primarily functions under the guidance of reason and the law. He stated that the secular magistrate alone has the public power to enact and coercively enforce laws — not the pope.

In the heavenly kingdom, being the realm of redemption and of spiritual and eternal life, the person substantially functions through faith and love. For Luther, man interchangeably lives in both kingdoms, that of sin and of grace. Conceived as an individual alone before God, man is freed from the direct “institutional support” of the church. This helped stimulate in the modern period the notion of the individual agent as “master of his destiny”, the centrepiece of much later political reflection. It directly sanctioned, in addition, the autonomy of secular activity in all domains which did not directly conflict with moral and religious practice. This development, when combined with the momentum for political change initiated by the struggle among religions, and between religions and secular powers, constituted a major new impetus to re-examine the nature of state and society.[2]

Yet it was not until the arrival of the Dutch scholar and jurist Hugo de Groot, better known as Hugo Grotius (1583 – 1645), recognised by most scholars as the Father of (Modern) Natural Law, that the course of individualism was altered in the most extreme secular manner, with his concept that natural law would still exist ‘etiamsi daremus Deum non esse’(even if we were to say there is no God).

[1] Oliver O’Donovan and Joan Lockwood O’Donovan, From Irenaeus to Grotius: A Sourcebook in Christian Political Thought, Grand Rapids, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 1999, p. 395.

[2] David Held, Models of Democracy, Cambridge, Stanford University Press, 2006, p. 58.