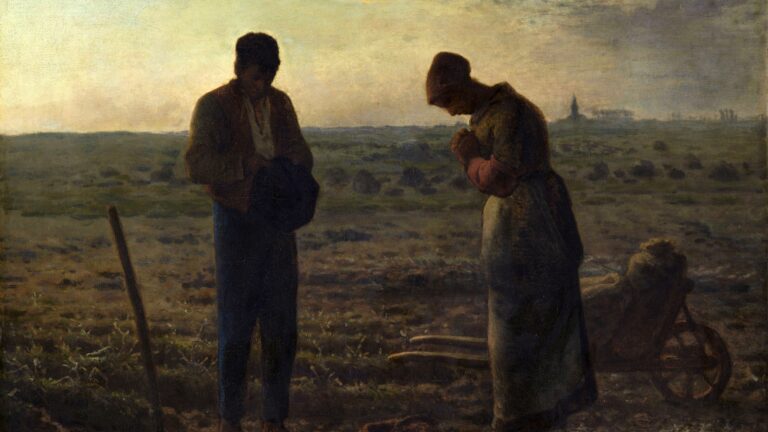

From an economic standpoint, central planning is widely viewed as ineffective. This understanding, backed by substantial scientific research, unfortunately resonates with the grim history of millions. Their experience of death, starvation, and impoverishment lend a tragic weight to this theory. Nevertheless, due to the popularity of radical left wing economic ideas in the West it is important to refresh the theoretical arguments as well as historical facts that disprove any idealisation of central planning.

Over 30 years after the collapse of the USSR, the romanticisation of central planning has re-emerged

due to technological progress and the availability of big data. Idealists believe that what was not possible to do in the 20th century, that is, to systematically plan an economic system, is now possible thanks to the large quantities of data that the internet makes available. In other words, in today’s era, numerous advocates of central planning on the Left, driven by the winds of progress, assert that the advent of advanced information technologies might rejuvenate their long-held dream of an economic system based on something else than private property and a self-regulated market, the mechanisms they view as deeply unjust.

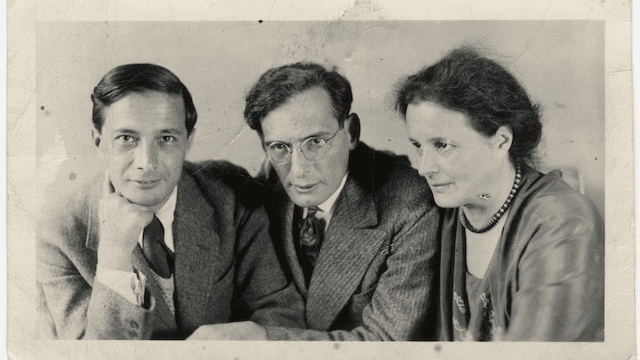

Given the resurgence of this concept, it’s vital to recall that even 20th-century scholars recognised the profound flaws inherent in such a techno-optimistic approach. One of the intellectuals opposing this mindset was Michael Polanyi, a Hungarian British polymath, whose ingenuity brought about important discoveries in physical chemistry, philosophy and economics.

Polanyi’s argument stands as a powerful rebuttal to the contemporary Left’s notion of a potential supercomputer, designed to process vast quantities of data and centrally organise the distribution of goods. These thinkers recognise that previous attempts to build this kind of system failed, but argue that the reason for the failure was that the mechanisms of gathering information about consumer demands were far underdeveloped. These leftist economists assert that if bolstered by a futuristic search algorithm and a computer capable of processing the amassed data, the shortcomings of central planning that led to such overwhelming misery could be circumvented.

The power of Polanyi’s counterargument against this notion comes from its fundamental nature.

Namely, the basic principles of epistemology—the philosophy discipline concerned with what knowledge is and how it functions. To demonstrate the problem with gathering information to systematically and centrally plan the life of an economy, Polanyi, in his work titled The Tacit Dimension, makes a juxtaposition between two types of knowledge. One is explicit knowledge, for instance the information that Budapest is the capital of Hungary, or numbers such as 1. These pieces of information can be given strict definitions and can also be written down both in formal and natural language that in turn can be accessed by other people. On the other hand, there is also tacit knowledge, the second type of knowledge, such as the ability to speak a language, use a particular tool, or perform activities like running or dancing. These activities elude strict formalisation and even conscious understanding. The challenge, according to Polanyi, is that the economic demands of consumers align precisely with the second, tacit type of knowledge that is not articulatable and formalizable for any data processing mechanism, neither for the human brain nor for artificial computer software.

Michael Polanyi also notices that virtually everything, even knowledge as strict and formal as the scientific one, is grounded in tacit implicit structures rooted in our consciousness so deeply that they are also impossible to formalize. Consider how frequently in daily life you’ve attempted to engage in a rational discussion on a topic, only to conclude that while you do understand something, you find it difficult to express it. Just as regular everyday discussions or other human interactions, science is an activity that involves communication and the articulation of ideas, and as a result, it suffers from exactly the same problem. As thorough as one might be in defining, articulating and formalizing ideas, at one point the end of the possibility of expanding knowledge any further will be inevitably reached. The same conclusion was independently reached in mathematics by Kurt Gödel, who proved that even something as rigid as mathematical formal systems are inconsistent and have statements that are impossible to prove or disprove—a recognition that had radical implications for all subsequent mathematical and philosophical thought.

While humans have no problem functioning with these boundaries in knowledge and expression—humans typically do not ponder about definitions of everyday objects as long as they function in practice—, strict definitions and formal structures are crucial for programming and computers, even a supercomputer with immense processing powers. The task of this futuristic socialist supercomputer would be to gather subconscious information from humans that is constantly and endlessly being changed as demands shift in a never-ending stream. Whereas in market economies consumers do not have to express every single desire of theirs and they can just go and purchase anything, articulating these pieces of tacit knowledge is very important for a project like that. That is why it is doomed in advance, unless the creators somehow develop the ability to formalize this fundamentally uncollectable knowledge and connect the machine directly to human minds. In this case though, organising the economy would not be important anymore, since neither economies, nor societies or human beings in their present form would exist any longer.

The insights provided by Polanyi are important for understanding the beauty of spontaneous natural order that conservatives value and stand for.

The power of his argument is that it is not applicable just to economics or the aforementioned disciplines of mathematics and science, like Gödel’s incompleteness theory.

It is simultaneously a warning to any ideology that attempts to guide and rationally engineer societies,

or for that matter, to conduct any experiments aimed at life engineering. While advocating for completely unregulated development is also challenging, there is hope that the dystopian totalitarian projects of attempting to rationally plan economies as well as societies, leading to the destruction of entire countries, will be relegated to the past, and the balance between rational, careful guidance and a natural self-regulating order will be preserved.