This article was originally published in Vol. 4 No. 3 of our print edition.

Are There ‘Worlds’ in Aquinas?

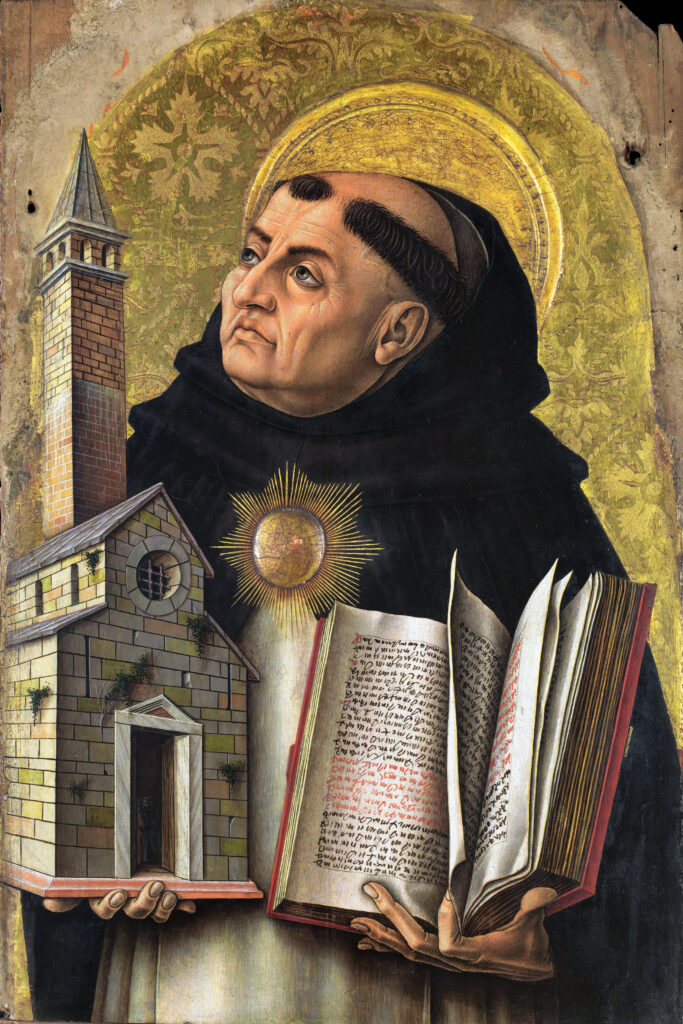

One could read Thomas Aquinas’s vast Summa Theologica without encountering the phrase ‘worlds of law’. The expression is not his. We might want to begin this foray into Aquinas, then, by asking: Are there ‘worlds’ in Aquinas?

There is one sense in which Aquinas certainly did not believe in worlds. This is the sense in which certain Greek philosophers held that there is an infinity of worlds. For instance, Epicurus wrote the following in one of his letters: ‘There is an infinite number of worlds (kosmoi), some like this world, others unlike it. For the atoms [are] infinite in number…[And thus] the atoms out of which a world might arise, or by which a world might be formed, have not all been expended on one world or a finite number of worlds, whether like or unlike this one. Hence there will be nothing to hinder an infinity of worlds.’1

This is an idea which Aquinas rejects in the part of the Summa that he devotes to the question: ‘Whether there is only one world or many?’ Here, he sharply contrasts his position with that of anyone who speculates—like Epicurus—that there must be an infinite number of worlds. Against them, Aquinas asserts what he calls the ‘unity of the world’. He claims, too, that the very concept of world denotes a ‘unity of order’. Because of this, he reasons, ‘it must be that all things should belong to one world’.2 The term ‘worlds’ can only be used metaphorically, therefore, when thinking about Aquinas.

The Worlds of Humans and Animals

Why, then, are we thinking about ‘worlds of law’ in Aquinas? The phrase is a nod to a short but highly influential book of twentieth-century theoretical biology by a Baltic German professor at the University of Hamburg, Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944). The son of a baronial family (in what is now Estonia) that was dispossessed by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Uexküll was a man of the right. However, as Geoffrey Winthrop-Young notes, Uexküll broke with basic Nazi racial doctrines.3 And in the decades since his death, his theories have deeply influenced philosophers on both the right (such as Martin Heidegger) and the left (such as Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari).

The book of Uexküll’s that occasions our talk of ‘worlds’ appeared in German in 1934. In English translation, its title reads: A Foray into the Worlds of Humans and Animals. This translation is not as precise as it could be. For Uexküll does not refer to ‘worlds’ (Welten). Rather, his title promises an essay on ‘the Umwelten of humans and animals’. And what are Umwelten?

This modern German term, Umwelt (in the singular), is worth knowing. It literally means ‘surrounding-world’. More idiomatically, we might translate it as ‘environing-world’, or simply, ‘environment’. There is a whole style of systems theory that is called ‘Umwelt theory’. So, Uexküll’s term has passed—in a technical register, at least—into English. But what is an Umwelt? And why can this twentieth-century concept help us to think about something like ‘worlds of law’ in Aquinas’s medieval philosophy, although he dogmatically rejects ancient theories of infinite worlds?

An Umwelt is a kind of world. But what does that mean? Well, an Umwelt is a structured totality. Uexküll calls it ‘an orderly whole’.4 However, it is an ordered totality within a greater one. It is an orderly whole within the orderly whole of all that is. Simply put, we might call an Umwelt a ‘world-within-a-world’. Uexküll, the term’s originator, also calls an Umwelt a ‘dwelling-world’. He writes: ‘Every animal, no matter how free in its movements, is bound to a certain dwelling-world, and it is one task of [theoretical biology] to research its limits.’5 If the world is—in a subjective sense—unlimited (we cannot perceive the end of it), a dwelling-world is a limited whole within the world. We can perceive the end of our dwelling-world in a particular way. Its limit is a horizon. That is to say, its limit is perceived as opening onto something beyond it. The end of a dwelling-world is constituted—in part—by how and where we dwell. Nevertheless, the fact that a horizon always points to more—to the world—shows that no dwelling-world is totally self-enclosed, but rather, is a world-within-the-world. Which is to say, an environment—or, even, a territory.

Dwelling-Worlds as ‘Territories’

And what is a territory? According to Uexküll, territory is a ‘subjective product’.6 What he means by this is that territory never belongs to the world as such. Rather, it belongs to a creature—or creatures—within the world. Territory is a dwelling-place that living things in the world make for themselves out of a part of the world. In other words, territory is a meaning that some creature—or some collective—realizes in and from the world. In Uexküll’s words:

[In an animal or human dwelling-world,] subject and object are interconnected with each other and form an orderly whole…[This is] the fundamental principle of the science of the environment (Umwelt): All animal subjects, from the simplest to the most complex, are inserted into their environments (Umwelten) to the same degree of perfection. The simple animal has a simple environment (Umwelt); the multiform animal has an environment (Umwelt) just as richly articulated as it is.7

This means that a dwelling-world, a territory, is what Uexküll calls a meaning-plan.8 It is a space of meaning constituted by living creatures within the space of all meaning—the world. Yet Uexküll believes that the whole world, like the dwelling-worlds that humans and animals inhabit, is itself a ‘meaning-plan’.9

The World as a ‘Meaning-Plan’

Uexküll is a highly sophisticated critic of Darwinism. Why? Because, in his words, Darwinists seem to be ‘extreme deniers of meaning as a natural factor’.10 This could call to mind what Aquinas says in his critique of ancient materialists, such as Epicurus: ‘[They] do not recognize any ordering wisdom, but rather believe in chance.’11 Uexküll, too, holds that it is impossible to think of all the dwelling-worlds of animals and humans, without recognizing that they are ultimately ‘fostered and borne along by the One’, whether we call that ‘forever unknowable’ One Nature or God.12

For Uexküll, as for Aquinas, there is only a world because there is one super-ordaining meaning-plan. Uexküll pictures the world as a grand harpsichord ‘over which an invisible hand glides, playing’. For him, the structure of the natural world is saturated with meaning, like a piece of Baroque music.13 In other words, the world is not a chance-structure (as Darwinism suggests), but an original meaning-whole.

So, too, Uexküll reasons that the territory—or dwelling-world—of any animal or human is a meaning-whole. But a meaning-whole that creatures generate within the world is not the meaning-plan of the world. Rather, it is just one plan, in and through which the drives, perceptions, and mutations of a certain being or a certain kind of being can be realized. It is not a world (Welt), but a dwelling-world (Umwelt).

Law as a ‘Dwelling-World’

In Aquinas’s thought, law seems to belong both to the world and to what Uexküll calls ‘dwelling-worlds’. Law belongs to the divinely ordained world, to be sure—but it also belongs, in complicated ways we will briefly explore, to animal and human dwelling-worlds.

Law is a salient aspect of the environment of living beings—both animal and human—and, as such, it is not only perceived by them, but, in the case of humans, it is concurrently produced by them. As with environments, so with laws—there are many of them. Some environments are healthy, others are not. But Aquinas recognizes that a diversity of legal regimes can be, within certain clearly defined limits, not only necessary but desirable. Further, he knows that even the same environment can be perceived differently by different inhabitants.

In Aquinas’s theology, all laws are somehow related—however corruptly—to the divine source of law, which is also the divine source of the world, and which Augustine of Hippo—and Aquinas, quoting him—calls ‘supreme reason’.14

Law as a ‘Meaning-Whole’

The first thing to note is that law is a meaning-whole in the Summa Theologica. ‘Law ordains things for an end’,15 writes Aquinas. Wherever there is law, therefore, there is meaning. This is what makes it interesting that Aquinas concedes that ‘even irrational animals, like rational creatures, share in the eternal law in their own way’.16 All animals participate in the meaning of eternity. Irrational animals’ dwelling-worlds are not bereft of divine meaning.

For eternal law is the highest divine law, in and through which the Godhead ordains everything for an end (as we have just heard that all laws, as laws, do). Eternal law is ‘the law called supreme reason’, by both Augustine and Aquinas, and it is in this law that irrational animals participate irrationally, while rational animals are called to participate in it rationally. Because irrational animals ‘do not share in the eternal law by use of reason’, Aquinas stipulates that we can refer to them as experiencing law or exhibiting lawfulness ‘only by analogy’. Because animals cannot know the end which the eternal law ordains, they cannot perceive the laws that shape their environments and behaviours as laws.17 For Aquinas, only humans do that—though they only ever do so imperfectly.18

Irrational animals participate irrationally in the world that is sustained by eternal law, and humans participate—or are called to participate—rationally. However, like the animals’ behaviours, which can only be called ‘law’ by analogy—so, too, human legal regimes only participate in the eternal law. The eternal law, here, seems to be something like Uexküll’s world (Welt). And the experience of law by both humans and animals can be seen as something like Uexküll’s dwelling-worlds (Umwelten). They are meaning-wholes, which creatures produce within a divine Whole on which they all rely—yet from which they are all distinct.

Aquinas makes this very clear in question 91, article 4 of the Summa Theologica. ‘Natural law’, he writes, ‘partakes of the eternal law in proportion to the capacity of human nature.’ He then reasons that this is why natural law needs to be supplemented by a ‘divine law’. Why? Because human nature in its worldly state is not the end that Aquinas’s Godhead has ordained for humans. The human dwelling-world is not the ultimate horizon of the human soul. Rather, the human soul is called to ascend to the vision of God after death. Therefore, Aquinas writes, ‘God gives an additional law that partakes of the eternal law in a higher way’.19

Animal species participate in the eternal law in animal ways; human laws and elements of natural law participate in the eternal law in human ways; but ‘divine law needed to supplement’ both human laws and natural law, because Aquinas thinks that humans—and only humans—are called to participate, after death, in a dwelling-world that is beyond every worldly dwelling-world.

This is what distinguishes human and non-human participation in the eternal law in Aquinas’s thought. It is not only that humans participate through reason and animals through drive or instinct. Aquinas notes that ‘irrational creatures are not ordained for higher ends than those proportioned to their natural powers’.20 And humans are ordained for higher ends. Humans are ordained by the eternal law to what we might call an infinitely high end. Animals’ experience of law, therefore, is proportionate to their species nature. And in the absence of the divine law, humans’ experience of law is similarly proportionate to their species-nature. There is much human legal reality which can—on this picture—be explicated without reference to what Aquinas calls ‘the end of eternal blessedness’.21 There is much human law that is just human law. Or, rather, that participates in the eternal law much as animals’ experiences of their own drives and instincts participate in eternal law. Both human law and animal law are ‘proportioned to their natural powers’.22 However, one of the strange and highly suggestive features of history is that human cultures do seem to foster rites, laws, and ideals which in some sense point infinitely beyond our species-nature.

Now, some disproportions to our species-nature are negative. Injustice would be a negative disproportion. But divine justice seems to be something like a positive disproportion to humans’ worldly nature, in Aquinas’s theory of law. It seems to set humans at a kind of distance, not only from plants or animals, but from themselves and their natural and historical dwelling-worlds. Divine law seems to create a dwelling-world—or the possibility of a dwelling-world—which is ‘not of this world’ (John 18:36).

‘Law belongs to the divinely ordained world, to be sure—but it also belongs, in complicated ways […] to animal and human dwelling-worlds’

Divine law is less a feature of the human environment—according to Aquinas—than it is an alluring echo within the human environment of a law that humans could never have produced. This seems to be the idea. Nevertheless, keeping to our theme of ‘worlds of law’, we could note that much human experience of law is—in Aquinas’s eyes, but here in Uexküll’s words—a ‘subjective product’.23 Now, the word ‘subjective’ here is not to be taken in a reductive sense. We will remember that, for Uexküll, in any natural dwelling-world, ‘subject and object are interconnected with each other and form an orderly whole’.24 Subjectivity, for Uexküll, is not bereft of natural objects. Rather, subjectivity is what constitutes a field of natural objects and navigates a system of intrinsically meaningful relations among them. So, too, it seems to me, Aquinas recognizes that the dwelling-worlds of what he calls human law are subjective products. This is by no means to suggest that the motivation behind human laws should be private. On the contrary, Aquinas cites the great Hispano–Roman bishop, Isidore of Seville, as saying: ‘Laws should be composed (conscripta) for the common benefit of citizens, not for any private benefit.’25

Nor is this to suggest that the logic of human laws should not be general. Again, Aquinas lifts this principle from the sixth-century Emperor Justinian’s great Body of Roman Law: ‘Laws need to be framed (constitui) to suit things that more frequently happen, and laws are not framed (constituuntur) to suit things that can happen once in a while.’26 Human laws, therefore, are to take the form of a ‘common precept’,27 which is ‘proportionate to the common good (bonum commune)’.28 ‘We call those laws just’, says Aquinas—quoting, here, Aristotle in a medieval Latin translation—‘that constitute and conserve happiness’ (factiva et conservativa felicitatis).29 Note the presence of the Latin word, conservativa, in this formulation. According to Aquinas, a just law must conserve collective happiness.

As this suggests, in Aquinas’s theory of law—as in Uexküll’s Umwelt theory—‘subject and object are interconnected with each other and form an orderly whole’.30 The objects of just law are human happiness (per Aristotle), the common benefit (per Isidore), and a set of things that more frequently happen (per the Body of Roman Law). None of this is subjective, in a modern sense. Yet note, too, that laws must not only conserve happiness but constitute it (per Aristotle), and that laws need to be framed (per Justinian) and composed (per Isidore).

All these terms denote the task of law-making. This task seems to be that of interconnecting subject and object to form an orderly whole in a city or territory. Neither the motivation for this task (law-making), nor the form of its product (law), should be private—or, in a negative sense, subjective. Nevertheless, Aquinas clearly recognizes that human law-making is a task—the eternal and natural laws are not sufficient for human collectives—and, thus, that the legal environments in which humans live are, though informed by and participating in both eternal and natural law, nevertheless, in a real sense, human products.

Human Law and Species-Being

It is in this complex sense that we can see human law as a sort of ‘dwelling-world’. There is certainly nothing negative, or decadent when Uexküll reasons that a bird’s nest, or a spider’s web, or a bear’s territory is a subjective product. What he means is that these forms of dwelling are responses to the world which are unthinkable without a species-being.

So, too, human legal regimes are responses to the world—and, for Aquinas, responses to both the eternal and the natural laws—which are yet unthinkable without human species-being, and indeed, without the subjectivities of concrete humans. In Aquinas’s own words: ‘All laws come from the reason and will of lawmakers…[Therefore,] human laws come from human wills regulated by reason.’31 It is because human laws are composed by concrete humans, for historical human collectives, that there are many legal regimes.

The ‘Worlds’ of Natural Law

There are many legal regimes—according to Aquinas—even before we take note of the history or geography of human law-making. In Summa Theologica question 95, article 4, for instance, Aquinas distinguishes between:

- a natural law which is common to all animals (eo quod est omnibus animalibus communis);

- and a natural law which is only common to all humans (for instance, ‘living sociably with others belongs to the natural law’—for humans, but not for all animal species).32

In Aquinas’s world-picture, these strata of legal reality and legal experience belong to:

- the kingdom-being of animals (if we may call it that, though the Linnaean taxonomy I am drawing upon here postdates Aquinas by roughly 500 years);

- and the species-being of humans qua singular humans (since they are, as singular humans, nevertheless ‘by nature social animals’).

But there is a further stratum of natural law which is:

3. only common to all human collectives qua one collective of many—namely, ‘the law of peoples’ (ius gentium).33

In itself, this is already a fascinating structure. Aquinas holds that humans have some law-experiences, law-impulses, or law-expressions which are shared generally with all animals; and others which are only shared with all other humans. It is not entirely clear, to me at least, whether both domains or ‘worlds of law’—the one world containing all animals, and the other containing only humans—are felt or experienced equally by humans. But Aquinas does take care to note that human species-law (2) is both stronger and more direct than what he calls the law of peoples (3).

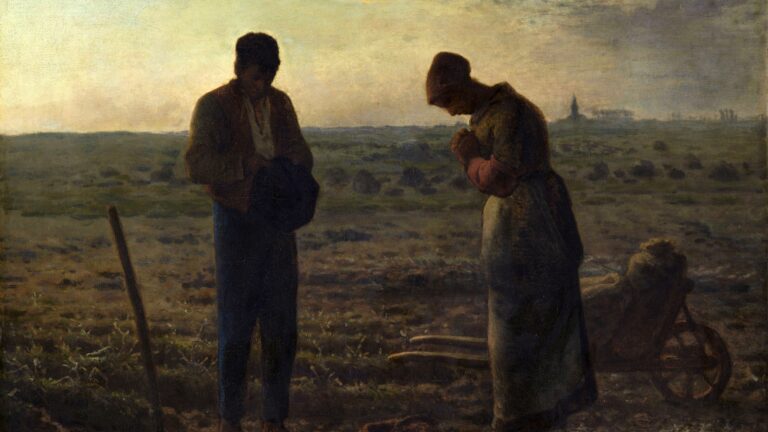

Now, the law of peoples (ius gentium) belongs to the law of nature (lex naturae). Yet Aquinas states that the law of peoples is only natural to humans in some manner (ius gentium est quidem aliquo modo naturale homini). This is because the law of peoples is rationally derived (derivatur) from ‘general principles of the natural law’.34 By way of contrast, Aquinas writes that the deepest stirrings of natural law are not experienced as a rational conclusion drawn from natural law. Rather, they are experienced as inclinations. There is—in his words—a certain set of ‘inclinations’ which humans ‘share with other animals’, among which we find—for instance—‘the sexual union of male and female, and the upbringing of children’.35

Long before we come to the promulgation of human laws, there is a sense in which natural law is a ‘subjective product’ (to again use Uexküll’s phrase). For the taproot of natural law is an experience of what Aquinas decides to call inclination. Now, no inclination is without its object—and Aquinas’s whole form of reasoning here suggests (whether we follow him or not) that the inclinations in question belong only to a singular human, a subject, because they in turn belong to the human species. But however we might wish to reconstruct the connection between subject and species, the fact remains that this species-rooted, object-oriented drive—this inclinatio—nevertheless cannot be conceptualized in the absence of a concrete living being. It is only a sensing, desiring animal which can be drawn to a passionate union (coniunctio) with another. In Uexküll’s sense, then, the deepest experiences of natural law in the Summa Theologica seem to belong to the ‘dwelling-worlds’ of both animals and humans, of which, there are many.

‘A diversity of legal regimes can be, within certain clearly defined limits, not only necessary but desirable’

The ‘Worlds’ of Human Law

And there are many human ‘worlds of law’, too. Beyond the several divisions of law we have just glanced at, there is a further one. For Aquinas notes that the world of positive law can be divided into the law of peoples—about which we have just spoken—and ‘the law of cities’ (ius civile).36 In a very real sense, the city is the human dwelling-world par excellence. The city is an environment that only a naturally social animal (naturaliter animal sociale), endowed with reason, could—or would—create. Although Aquinas underscores that all just laws are derived from natural law, he recognizes that ‘The general principles of natural law cannot be applied to all peoples in the same way because of the great variety of human affairs. And so, there are different positive laws for different peoples.’37 To be sure, much of the diversity in human laws is—for Aquinas—regrettable, or even reprehensible. Much of this diversity can be attributed to what he calls the ‘corruption of law’ (legis corruptio).38 Nevertheless, there remains a positivity, for Aquinas, in the diversity of human laws. The law of cities should never cancel out the natural law—yet there are numerous ways in which the laws of one city should, according to Aquinas, differ from the laws of others. There should not be only one human dwelling-world. The staggering variety of human affairs should give rise to a variety of human laws. Or, put differently, there should be more than one human polity, more than one legal regime, more than one ‘world of law’.

Different Experiences of Any Particular ‘World of Law’

Aquinas recognizes that, within the same ‘dwelling-world’, a single set of laws will be experienced differently by different subjects. For instance, he notes in passing that sleepers inhabit a world in a radically different way from those who are awake. It is not that the law no longer applies to them, but rather that they—in some sense—no longer apply to the law.39 Further, he is aware that children inhabit a ‘world of law’ in a radically different way from those who are older. Aquinas speaks, for instance, of their ‘lack of age’ (defectum aetatis),40 because of which—he writes—‘the law is not the same for children and for adults’.41 A world of law is not the same, we might say, for children and for adults.

Finally, a particular law is experienced differently by those who ‘do voluntarily’ as the law enjoins, and by those who only keep the law ‘out of fear’: ‘Fear of punishment’, writes Aquinas, ‘is the discipline of laws (disciplina legum)’.42 Here, it is not the laws but the experience of laws which will differ, perhaps quite drastically, from one subject to another. Of course, the purpose of laws is, in part, to create this difference. Or so we might infer from a sentence of Isidore’s, which Aquinas quotes with unqualified approval: ‘Laws were established so that fear of them would curb human audacity, and that innocence would be safe in the midst of the wicked, and that the fear of punishment would restrain the ability of the wicked to inflict harm.’43 We could perhaps not hope for a better articulation of what a ‘world of law’ is meant to be in the Summa Theologica. The city is a human dwelling-world in which hubris is punished, innocence is protected, and the ability to lawlessly inflict harm is diminished. In other words, it is a dwelling-world (Umwelt) in which humans, through natural reason—and perhaps, too, in light of the divine law—seek to further the ends of a world-generating, eternal law that both Augustine and Aquinas call ‘supreme reason’.44

NOTES

1 Epicurus’s ‘Letter to Herodotus’, according to Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Greek with English trans. by R. D. Hicks (Harvard University Press, 1925), book 10, paragraph 45.

2 Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (Forzani, 1925), part I, question 47, article 3, 383–384. Note that Aquinas names Democritus, and not Epicurus.

3 Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, ‘Bubbles and Webs: A Stroll through the Readings of Uexküll’, in Jakob von Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with a Theory of Meaning, trans. Joseph D. O’Neil (University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 226–229.

4 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 49.

5 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 139.

6 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 103.

7 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 49–50.

8 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 160. (His stress.)

9 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 160.

10 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 174.

11 Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I, question 47, article 3, 383–384.

12 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 135. (Typography lightly modified.)

13 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 208.

14 Thomas Aquinas, Treatise on Law, trans. R. J. Regan (Hackett, 2000), 7; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 1, 649.

15 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 8; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 1, 650.

16 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 8; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 1, 650.

17 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 7–9; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, articles 1–2, 649–651.

18 This is how I read him, at least, when he writes that ‘natural law is our participation in the eternal law, [and] human law falls short of the eternal law’: Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 55; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 96, article 2, 684.

19 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 12; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 4, 653.

20 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 13; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 4, 654.

21 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 11; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 4, 653.

22 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 13; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 4, 654.

23 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 103.

24 Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 49–50.

25 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 52; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 96, article 1, 682–83.

26 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 52; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 96, article 1, 682.

27 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 53; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 96, article 1, 683. (Translation modified.)

28 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 52; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 96, article 1, 682–83.

29 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 3; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 90, article 2, 646.

30 Uexküll, Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, 49–50.

31 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 66; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 97, article 3, 693.

32 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 50; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 4, 681.

33 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 51; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 4, 681–82.

34 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 51; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 4, 681–82.

35 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 36; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 94, article 2, 669–70.

36 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 50; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 4, 681.

37 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 47; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 2, 679.

38 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 47; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 2, 678–79.

39 I am reading this somewhat freely: Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 34; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 94, article 1, 669.

40 I am reading this somewhat freely: Aquinas, Treatise on Law, p. 34; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 94, article 1, 669.

41 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 54; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 96, article 2, 684.

42 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 44; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 95, article 1, 677.

43 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 44; Aquinas, SummaTheologica, part I–II, question 94, article 1, 676–77.

44 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, 7; Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part I–II, question 91, article 1, 645.