You can read the first and second parts of the article here.

The Worldview

As we established in the first two chapters: the primary engine and embodiment of the modern, anti-authoritarian narrative of progress is, on the surface, a technocratic rationalism that is unaware of its own post-theological roots. This mode of thinking, which reduces all of reality to measurable, calculable, and utilizable parameters, is not merely a tool for understanding the world, but a profound metaphysical stance that fundamentally defines our relationship to reality. To understand its destructive consequences, we must trace it back to the very birth of modern reason.

For premodern thought, the pinnacle of cognition was intelligentia (Greek: nous), which meant not simply understanding but the intuitive grasp of ideas—the eternal forms and principles behind things.1 For Plato, reality consisted of the ideas, not the matter in which they are merely reflected. The task of nous was the contemplation of these essences, a synthesizing faculty that sought the whole and origin of things.

In contrast, the modern term ratio stems from the Latin for ‘counting, calculation’ and denotes a discursive, analytical faculty that compares pieces of the phenomenal world and draws logical conclusions. The intellectual decline of modernity can clearly be traced in the process by which ratio gradually subjugated and then eliminated the very legitimacy of intelligentia.

This shift began—following the nominalist thought of late Scholasticism—with Francis Bacon and René Descartes.2 Bacon replaced the intellect understood as nous with the English term ‘understanding’—literally ‘standing under’ something—signalling that cognition was no longer directed toward the principles above phenomena but toward the material mechanisms beneath them. Descartes’ sharp separation of the thinking thing (res cogitans) from the extended thing (res extensa) stripped matter of all inner, spiritual qualities, reducing it to a mere object—a machine describable through mathematical formulas. Once modern thinkers declared that no higher form of cognition exists beyond reason (ratio), whatever lay beyond the reach of rational calculation—essence, symbol, transcendence—became, for all practical purposes, indistinguishable from the non-existent.

Dezső Csejtei, following Heidegger, illuminates Western man’s fateful choice using the Greek concepts of physis, logos, and technē. Physis is being itself, nature, a reality that unfolds on its own but also conceals itself, which deserves reverence.3 Logos is human reason, speech, logic, which seeks to uncover physis, to name it, to wrest it from concealment. And technē is knowledge, craft, technology, which mediates between them. According to Csejtei, the tragedy of Western man lies in the decision to align technē not in the service of physis, but alongside logos. Instead of technology becoming the careful steward of nature, it became the violent tool of calculative reason, used to subjugate physis.4

‘Instead of technology becoming the careful steward of nature, it became the violent tool of calculative reason’

The political embodiment of this logic, which objectifies and en-frames everything, is today—despite the outward forms of ‘liberalism’ and ‘democracy’ and the ideology associated with them—the state, in which we have seen, in several cases, the worst-case scenarios of the Hobbesian Leviathan become reality.5 The 20th-century communist and national socialist systems were clearly such, but it is an illusion to think that systems called ‘liberal’ or ‘democratic’ stand on radically opposite principles: the narrative telling the story of the state may be different, but the technological framework underlying the state can be very similar.

After the modern revolutions destroyed traditional, hierarchical structures, the resulting vacuum was filled, in Max Weber’s terms, by ‘bureaucratic authority’. The modern state bureaucracy is the political operating system of the Heideggerian Enframing: a rational, impersonal machine which, by rejecting organic, social forms of authority in favour of impersonal, mechanical, and technical processes, simultaneously liquidates all intermediate, organic communities and freedoms in the name of equality and central efficiency.

‘Equality’ in the age of technical rationality is mostly mere rhetoric: it refers to the mechanical ‘equality’ of the components of a machinic organization, which takes the ‘smoothest’ possible operation of a technically conceived apparatus as its model. Parallel to the growth of so-called welfare institutions, the ‘Enframing’ has actually increased its power over the individual and his organic communities to an unprecedented degree, subjecting every area of life to regulation and administration.6

If we go back in time a few centuries, we can observe that the most unbridgeable gap between the modern and premodern worlds lies not primarily in the goals of the political order, but in their comprehensive understanding of the nature of reality. This also impacts politics, making organic authority possible in one worldview but not the other. For the ‘methodological naturalism’ of modern science, the ‘cosmos’ of the ancients is fundamentally a lifeless, material reality, a vast mechanism described by the laws of science and shaped by technology.

In contrast, for the premodern cosmic view, the world was a living, ordered, and meaning-filled Cosmos—the Greek word κόσμος (kosmos) simultaneously means order, lawful governance, and ornate beauty. In this worldview, beings were not randomly co-existing atoms but parts of an organic, hierarchical whole, in which every element points to a divine principle above it, from which it derives its place and meaning.

It is not a question of which worldview is ‘truer’. However much more precise Galileo’s telescope may be than Ptolemy’s, or the descriptions of his astronomical successors about the physical system of the universe—the movement and physical properties of the planets—than earlier ideas, it seems that here, regarding the purpose of cosmological systems, we are dealing with incommensurable realities. The premodern view of nature and its various articulations in natural philosophy represented a different ‘paradigm’, to use Thomas Kuhn’s term, as it stood on metaphysical, not material, foundations. If we want to remain intellectually honest, we cannot, based on Kuhn, declare one worldview ‘true’ and the other ‘false’.7

According to Foucault’s central thesis, ‘truth’ is not an objective, neutral fact that the scientist-historian ‘discovers’, but something that power—as a latent, ideological substructure—actively produces in every age. The power-‘discourse’ does not describe reality; it is an ‘exclusionary principle’, a subtle and pervasive tool of exercising power. Discourse is the power that people ‘strive to seize’.8

‘Discourse is the power that people “strive to seize”’

As Henry Oldmeadow notes, ‘a materially inaccurate but symbolically rich view’ was replaced9 by a view that may be materially more accurate, conveying more certain knowledge about the material structure of the universe, but it fails to consider that the material facts observed in the universe always mean something to the subject observing them. It is a mere preconception that the ‘bestowal’ of meaning upon things stems from a mental tendency equivalent to an arbitrary anthropomorphization of the cosmos. In materialism, the universe is still observed by a subject. Thus, it goes without saying that if this subject wishes to say anything worthwhile about it, he too will evaluate the objective world from the perspective of the subject.

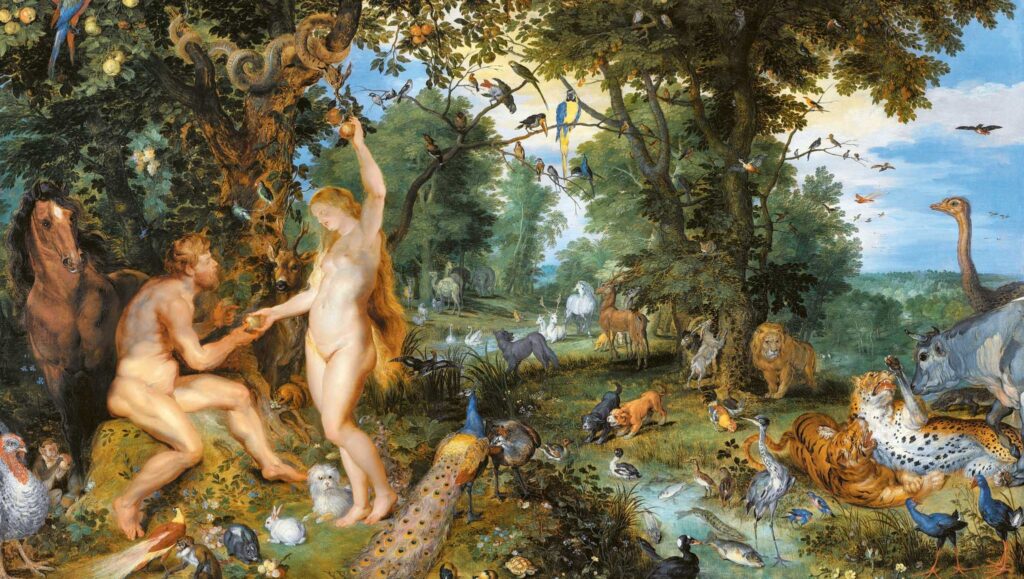

The premodern view of nature may seem naive compared to the modern focus on quantities and measurements, but this apparent naivety is rooted in a deeper realism. The modern view fails to consider that the meaning discovered in the universe stems, above all, from the premodern consciousness interpreting things not as existing in themselves, but as representations of spiritual beings (or of a single, supernatural Being).10

In modernity, things are not symbols of anything; the things of the world are no longer signs of God: they are merely objects describable by quantitative parameters. The premodern consciousness, however, starts from the premise that reality—whatever form it takes—is given only to the observer. We cannot ask, for example, what the world is ‘like when we are not observing it’: this is not only a logical and practical absurdity but a completely meaningless statement. The task of the subject is precisely to make the cosmos meaningful. The ‘bestowal of meaning’ is not naivety, but a task. Making things meaningful arises only in relation to man.11

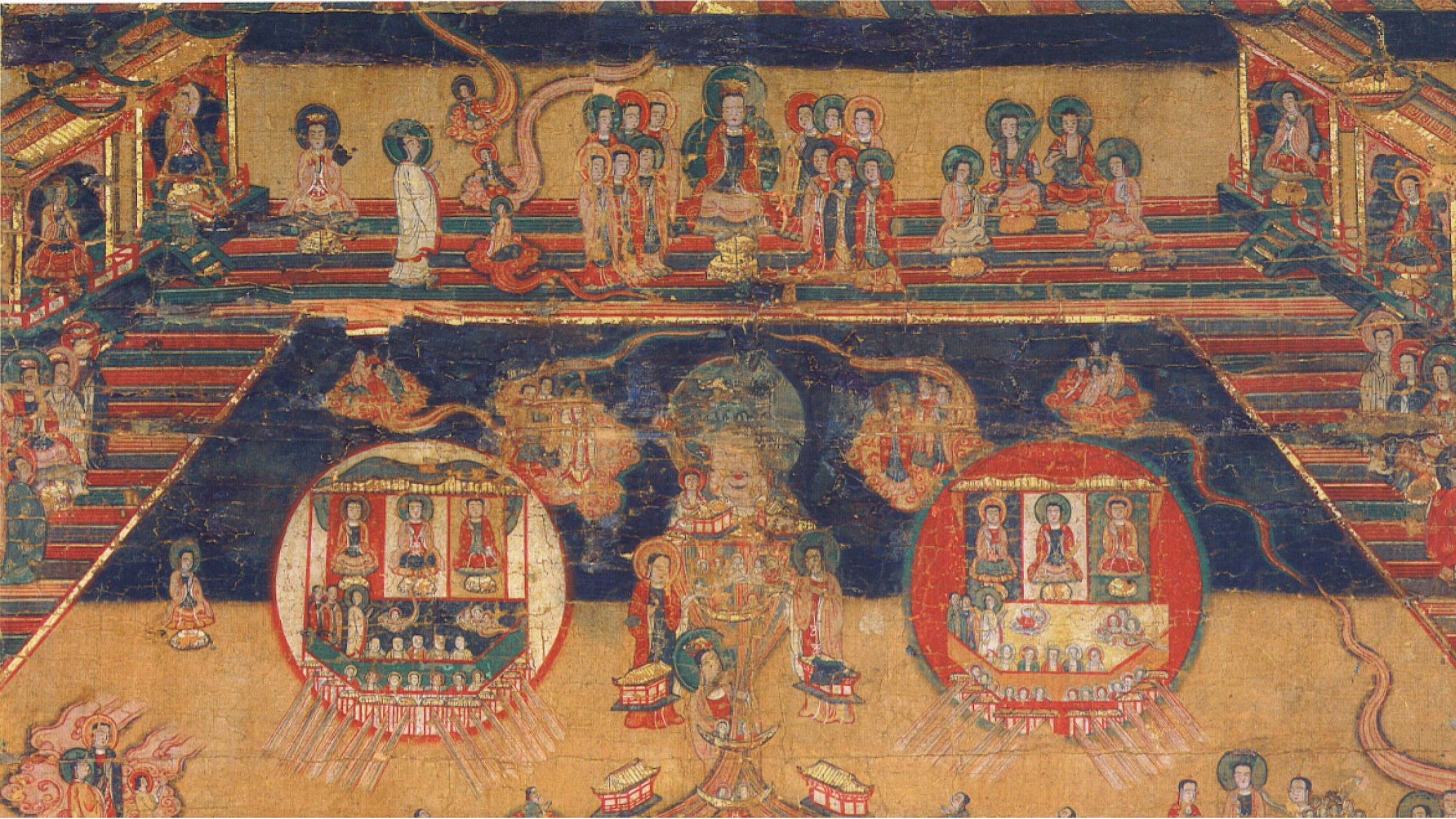

To understand the difference between the premodern analogical-symbolic worldview and the modern ‘analytical’ one, it is worth turning to a universal symbol present in almost every culture. The idea that the gods dwell in the sky (or on high mountaintops) is not merely the product of a naive, ‘anthropomorphic’ mind that ‘could not conceive’ of height or greatness as ‘purely physical.’ For the premodern mind, the height and immensity of the Sky relative to the Earth was a real symbol of transcendence; from this arises the symbolism of the gods ‘dwelling in the sky’ in most archaic cultures.12 The general symbolism of celestial bodies and stars—viewed from the Earth, their brightness and distance, and the associated ideas of transcendence and perfection—signified that ‘every phenomenon depends on a higher Reality, which defines us.’13

From a materialist standpoint, it is impossible to grasp the reality of symbols and symbolic thinking; consequently, one cannot understand the cultural and worldview-related dimensions of premodern man and can only describe the most external, material aspects. Approaching the philosophy of history—or the science of history in general—from a purely materialist perspective causes enormous distortion.

As Titus Burckhardt states: while modern science always examines the materia-aspect of things (that is, what appears in relation to a form), the premoderns understand things as meaningful and significant wholes not by the analytical examination of their matter, but by interpreting their form within a higher system of coherence.14

One should proceed with caution regarding careless opinions about archaic conceptions of the cosmos: it is an undeniable fact that all experience is a value judgment of an experiencer, and the objects under examination can only be thought of as existing ‘merely’ in terms of their measurability according to a highly reductive and limiting perspective. Different cosmologies are grounded in different modes of thinking and conceptions of consciousness. It is not primarily the quantity of knowledge about the world (its poverty or expansion) that determines these sharply divergent worldviews, but the worldview itself—and the corresponding science—through which premodern and modern (mostly post-Enlightenment) consciousness defines man’s interest in the world.

‘Different cosmologies are grounded in different modes of thinking and conceptions of consciousness’

The premodern conception, however, also saw the world as hierarchically structured, consisting of countless levels of existence from the lowest mineral level to the highest: God. The political idea of hierarchy follows from this cosmological image, not the other way around—that an already existing earthly hierarchy, arising from ‘production relations’ or ‘exploitation’, was projected onto the world. This latter view reflects purely modern ideological preconceptions. Premodern man did not think this way: any medieval ‘mirror for princes’—or the works of Plato—demonstrates that the idea of the cosmos occupied a much deeper, more fundamental level than politics, which is better understood as a derivative inferred from the intuitively perceived order of the cosmos.

In the medieval Christian world, God, as the ultimate principle of all things, was also the absolute measure of all things; the entire hierarchy depended on His existence and was directed toward Him. He held the world together, from the highest to the lowest. Whether it be the distinctions between lower, earthly, and upper worlds; between mineral, plant, animal, and human forms of life; or the nine successive spheres of the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars (i.e., the angels, archangels, and thrones), all describe hierarchical (metaphysical) degrees of existence.

In non-Christian religions and cultures, such as Uralic and Altaic shamanism, the World Tree—found across much of the world—depicts the same hierarchically ordered nature of reality. Its top reaches the sky, and in Uralic-Altaic mythologies, one of the shaman’s central tasks is symbolically ‘climbing’ the World Tree, reaching the Sky where the supreme Deity ‘dwells’.15 The king (or khan, or Chinese emperor) was seen as God’s ‘reflection’ on earth, for there was no question of God’s existence.

- In the Middle Ages, intellectus was used to translate the Greek νοῦς (nous), which does not simply mean understanding but denotes a concept rooted in Greek philosophy—especially in the Platonic and Plotinian Neoplatonic traditions—referring primarily to the comprehension of truth or reality. The term is intelligible only when interpreted within the framework of Platonic philosophy. Just as for Plato true reality consisted of the ideas, not the material world in which they are merely reflected, so the Platonic nous must refer above all to the apprehension of the ideas—that which lies beyond material reality and is truly real. (See, for example, Plato’s Timaeus.) ↩︎

- Late Scholastic nominalism is a crucial intellectual precursor to modernity because it dismantled the medieval realist worldview that had underpinned prior philosophy. Nominalism—particularly through William of Ockham—atomized reality into discrete, individual facts, undermining the metaphysical foundation of knowledge. Modern philosophy sought to fill the resulting vacuum in two ways: empiricism, with its focus on experience (Bacon), and rationalism, seeking certainty in the thinking self (Descartes). Together, they paved the way for the ascendancy of purely calculative reason (ratio) over essential insight (intelligentia). ↩︎

- ‘Physis is certainly one of the most complex concepts. Its main meanings important for us are the following: 1) It means not only the totality of beings, their fullness—which our word ‘nature’ expresses—but also that which is located behind them and serves as their foundation: being.’ (Dezső Csejtei, ‘Filozófiai töprengések korunk szellemi állapotáról’, Kommentár 2023/4, 67–83, p. 72.) ↩︎

- Ibid, pp. 71–73. ↩︎

- As the extremely sharp-sighted Tocqueville formulated it ‘in the nick of time’: ‘Above those men arises an immense and tutelary power that alone takes charge of assuring their enjoyment and of looking after their fate. It is absolute, detailed, regular, far-sighted and mild. It would resemble paternal power if, like it, it had as a goal to prepare men for manhood; but on the contrary it seeks only to fix them irrevocably in childhood…’ (Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans James T. Schleifer, Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, 2010, p. 1250.) ↩︎

- As Tocqueville’s modern follower, the outstanding Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, states: ‘The vistas of De Tocqueville relate to a peaceful evolution (or, if we prefer, degeneration)—a slow process of interaction and decline, with men becoming gradually more like mice, and states more like Leviathans. His error is merely one of “timing.”…Under these circumstances mildness will have to be replaced by concentration camps, mass exiles, deportations and gas chambers, until and unless a totally new and uniform generation grows up.’ (Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Liberty or Equality: The Challenge of Our Time, The Caxton Printers, Ltd, Caldwell, Idaho, 1952, p. 30.) ↩︎

- According to one of the main theses of Thomas Kuhn’s famous book, it is impossible to compare successive paradigms due to the ‘change of meaning’ of the concepts used in the theories. (Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, pp. 43–52.) ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, The Discourse on Language, trans Alan Sheridan Smith, New York, Pantheon Books, 1972, pp. 10–11. ↩︎

- Henry Oldmeadow, ‘Tudomány, szcientizmus és önpusztítás’ (‘Science, Scientism, and Self-Destruction’), Ars Naturae, http://arsnaturae.hu/hu/folyoirat_3-4/oldmeadow/tudomany_szcientizmus_onpusztitas, accessed: 7 February 2025. ↩︎

- As Tamás Molnár formulates it: ‘…We cannot interpret the world, our existence, and its experiences without presupposing the existence of an origin that serves as the source and foundation (arché) of all other beings, which is not so much a creator as an ontological substrate. The original must always and by its essence be distant, secret, hidden, yet surpassingly and powerfully real, since this distance and power signify and testify to its original status, its limitlessness, in the mirror of which everything else—man and phenomenon—gains meaning, becomes explicable.’ (Tamás Molnár, A gondolkodás archetípusai, Kairosz Kiadó, Budapest, 2001, p. 11.) ↩︎

- A famous biblical myth also reflects this idea, in which Adam ‘gave names’ to the animals. ↩︎

- Mircea Eliade discusses the phenomenon of sky gods in detail in his study The Sky and the Sky Gods. According to Eliade, throughout the history of human religions, the belief in a sky god who created the universe and guarantees the fertility of the Earth (for example, through rain) is almost universal. (Mircea Eliade, Patterns in Comparative Religion, New York, Sheed and Ward, 1958, pp. 38–124.) The word ‘primitive’ here should be understood in its literal sense, that is, as ‘original’ or ‘primary’. ↩︎

- Oldmeadow, ‘Tudomány, szcientizmus és önpusztítás’ (‘Science, Scientism, and Self-Destruction’). ↩︎

- ‘The traditional view of things is, above all, “static” and “vertical”. It is static because it refers to permanent and universal qualities, and it is vertical in the sense that it links the lower to the higher, the transient to the imperishable. The modern view, by contrast, is essentially “dynamic” and “horizontal”; it is not interested in the symbolism of things, but in their material and historical contexts.’ (Titus Burckhardt, The Mirror of the Intellect: Essays on Traditional Science and Sacred Art, Cambridge, Quinta Essentia, 1987, p. 25.) ↩︎

- Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, trans Willard R. Trask, Bollingen Series LXXVI, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2004, pp. 139–140. ↩︎

Related articles: