The idea that technology can help us achieve our individual and collective aims, a concept deeply rooted in the European ‘Enlightenment.’ This view of things, however, can also be called the ‘Faustian idea’ (or bargain) according to such authors as Oswald Spengler.

Has technology become a worldview, the Weltanschauung of the most ‘progressive’ age, of ‘Enlightenment’s Enlightenment,’ or is it still just a ‘useful tool’ to help make people’ lives easier? Perhaps it would be naïve to give a simple answer to this complex question.

I am writing this ‘technology-critical’ essay on the most advanced technological device and those who may read it are also most likely doing it on a computer screen. Being ‘contemporary’ however does not mean that one is ‘modern’ (at heart), even if the two most often coincide these days. All of this makes it clear that the main issue here is not primarily rooted in the problem of the use of technological tools, but of the way of looking at them.

The colloquial phrase Faustian bargain refers to a German legend from the second half of the 17th century, in which Doctor Faustus, an unsatisfied alchemist, makes a bargain with the Devil, selling his soul in exchange for previously unattainable magical powers and unlimited pleasures, with positive short-term results and a catastrophic denouement.

Spengler believes that Western culture differs from other cultures primarily because of its ‘Faustian’ character.

As he writes:

‘The bent of the Faustian Culture…was overpoweringly towards extension, political, economic or spiritual. It overrode all geographical-material bounds. It sought — without any practical object, merely for the Symbol’s own sake — to reach North Pole and South Pole. It ended by transforming the entire surface of the globe into a single colonial and economic system.’[1]

In 1932, another German author, Ernst Jünger, one of Spengler’s highly influential contemporaries, emphasized in his work The Worker (Der Arbeiter) that the immanent desire for activity of the Western man—his constant movement appearing in science, politics, and state organization—is opposed to the ‘constancy’ of non-Western societies.[2] This, according to Jünger, refers to a radical ‘dimension of activity’ which includes the processes of quantitative work, the material perception of ‘production’ as well—but also symbolizes the transformation of the world by human activity. The main tool of this work is the machine, which is also a great symbol of the ‘most modern’ age. And the hero in the form of an ideal-typical figure, ‘the Worker’ emerges—but Jünger’s Worker is not the idealized ‘working class’ of the communists. The Worker, like the alchemist Faust, is a designer, an adjuster, the operator of machines, ‘magic-tools’ of sort into which he pours his soul and desire for power as spiritual fuel.

This appearance of the Worker on the one hand enabled the expansion of Western culture through the process of colonization over the entire globe (direct–material conquest) and on the other hand the expansion of the Western type of life to the rest of the world (indirect–spiritual conquest), which manifests itself above all in the permeation of the world by technology—now actually encompassing the whole globe.

Our modern concept of civilization is closely related to the idea of technical civilization.

The use of high-level technical tools, scientific innovation, and relentless development are almost the same thing as being at the forefront of culture and being connected to the progress of humanity. This is what primarily distinguishes us from what is premodern.

There is no doubt that the idea of technological progress is, in the eyes of most, a solution to many of the problems from which humanity seemed to suffer in the past. But doesn’t it also contain and create new problems that seem even more serious than before?

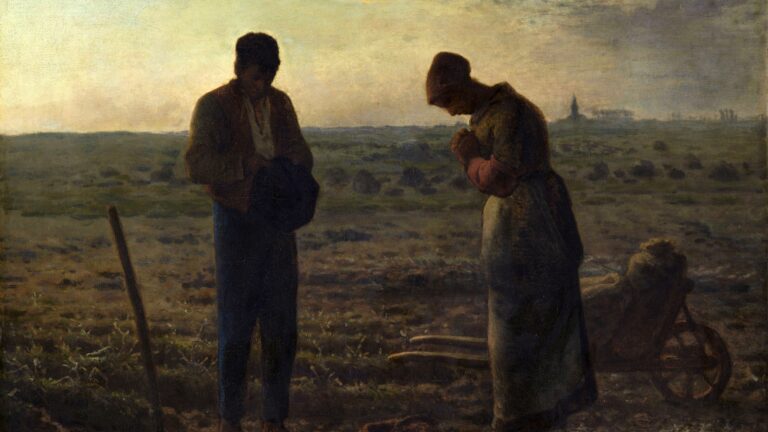

Civilization—at least according to the Spenglerian evaluation and distinction between ‘Culture and Civilization’—is also the part of a wider historical circle. (Also called ‘Culture’ by Spengler.) Culture, preceding civilization in the life cycle of cultures, does not use machines, or uses few and low-level machines, because it does not need technology—just as a healthy young person does not need different supports or mechanical prostheses to be able to walk or stay alive. Civilization, on the other hand, is like old age: stiff, tired, senescent, to borrow an organic analogy. While it thinks it can conquer the infinity that lies before it through machines, it actually needs machines to sustain itself artificially, with ‘respirators’ to keep it alive for just a little while longer.

As Georg Jünger, the brother of Ernst Jünger, wrote in his essay The Perfection of Technology:.[3]

‘One look at the machine tells us that here we are facing the dead side of existence, a world of sterile, sexless machines and lifeless automatons. The machine is not a clay golem animated by spells, nor a mentally active homunculus. Rather, it is a dead automaton, a robot that repeats the same work process tirelessly and in the same way.’[4]

In Man and Technics Spengler summarizes the Faustian condition in the following way:

‘All things organic are dying in the grip of organization. An artificial world is permeating and poisoning the natural. The Civilization itself has become a machine that does, or tries to do, everything in mechanical fashion. We think only in horse-power now; we cannot look at a waterfall without mentally turning it into electric power; we cannot survey a countryside full of pasturing cattle without thinking of its exploitation as a source of meat-supply; we cannot look at the beautiful old handwork of an unspoilt primitive people without wishing to replace it by a modern technical process. Our technical thinking must have its actualization, sensible or senseless.’[5]

However, it is still worth making a clear distinction between technique and technology.

Technique comes from the Greek word ‘techné’, its meaning originally encompassed all actions that could be described by concrete action, ‘things done’ (pragma). Technology comes from the combination of the words techné ‘craft’ and ‘logos’, i.e. ‘doctrine’, and literally means ‘talk about technology.’ This included, for example, politics, as well as the arts and medicine. For the Ancient Greeks, the meaning of technique could therefore have been broader than that of technology.

Today, however, technology has attained new meanings: on the one hand, it is used synonymously with pragmatic, optimal or utilitarian practice, and on the other hand, it also means the idea of technical domination and mastery. In modernity life becomes technical, because the idea of technology permeates existence: the primary language of modernity is an implicit theology—instead of talking about God, the discourse is about technology. The hegemony (or totalitarianism?) of technology holds a special attraction upon modern life. It is the sole source of desirable opportunities for advancement.

In order to have a good salary today one must have marketable skills which are somehow related to the maintenance or expansion of the technological infrastructure. For the pragmatics of technology, ‘mere bookish knowledge’ (humanities) is economically irrelevant. The role one plays in the modern social hierarchy depends largely on mastery of technology. At the top of the workforce hierarchy stand various engineers and IT engineers, (i.e. programmers), a veritable ‘aristocracy’ of machine designers who access an overview of the situation (or at least they believe so). This hierarchy extends downwards through technicians of different ranks, down to mechanics, who are also arranged in a hierarchical relationship with each other, all the way to the simple unskilled worker. From the richest and most influential persons to the most socially insignificant and poorest, everyone lives, exists, experiences, and breathes under the spell of the machine: they define themselves in relation to the machine and, in the ultimate sense, spend their lives at the service of technology.

Various machines also existed before modernity: the builders of the Gothic cathedrals of the Middle Ages also had considerable engineering and pragmatic knowledge, so it was not that they lacked the necessary knowledge, but above all they lacked the formulation and application of the machinic idea. The view that we must ceaselessly improve the human destiny by taking human destiny ‘into our own hands’ is a historically new development, not much older than a couple of centuries at most. The machine itself is only the consequence: it means something that makes human life actually ‘easier’, and the undoubtedly raw trials of life in the material world more bearable, and eventually, makes life itself so comfortable that attachment to the world of the machines becomes a virtue and a norm.

The machine in modernity is the product of an overactive problem-solving thinking.

It belongs to a form of intelligence that our contemporaries are too inclined to identify with total intelligence.

However, just as rejecting rationalism does not mean rejecting reason, we do not think that the radical technicization of the world is the primary, indeed the only, cause of the crisis of modernity.

While not to dismissing technology, we believe that a radical ‘detechnicization’ is the solution to the ever accelerating crisis of the modern world. We do not want to attack the advantages of technology that are obvious to everyone and the opportunities that it opens, but we want to note that without the current, exaggerated omnipresence of technology, it would be impossible to impose ideas, lifestyles, or political regimes on the entire Globe. The current level of standardization or possibility of a world war would also be impossible: and we do not only mean the standardization of clothes, buildings, products, and consumer goods, but also the standardization of ideas and thoughts, the ‘great levelling’, which only continues and radicalizes the ‘great ideas’ of 1789. And last but not least: it would not be possible to have an ecological crisis. Materialistic mentality, which is mostly ideologically responsible for the exploitation of the entire globe’s physical resources (while trying to cover it up with the peculiar lie of ‘global greenwashing’) is also closely connected to the mentality of the totalism of technicization.

[1] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West Volume I. Form and Actuality. trans. Charles Francis Atkinson. (London: George, Allen, & Unwin), 1926, 335.

[2] See. in English: Ernst Jünger, The Worker: Dominion and Form. Northwestern University Press, 2017.

[3] See. in English: The failure of Technology: Perfection Without Purpose. Independently published, 2021.

[4] Friedrich Georg Jünger, Die Perfektion der Technik. Frankfurt am Main, Vittorio Klostermann, 2010 [1939], 175.

[5] Oswald Spengler, Man And Technics, Routledge, 2018, [1932] 94.

Read more from Zoltán Pető: