On 1 February, President Joe Biden sat next to US House Speaker Mike Johnson and House Minority leader Hakeem Jeffries at the National Prayer Breakfast on Capitol Hill. While Johnson had previously drawn attention by stating that America was founded as a Christian nation, other Republicans from Texas, Oklahoma, and Kentucky drew wider scrutiny in arguing that the United States was founded on ‘Judeo-Christian’ principles.

The same sentiments have been shared by conservative leaders, such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, and even by former president and now candidate Donald Trump, who said:

‘We are committed to defending innocent life and to upholding the Judeo-Christian values of our Founders and of our founding.’

The term ‘Judeo-Christian’ has been used repeatedly by European theologians, politicians, historians, and philosophers—from Jacques Derrida, the left-wing French philosopher, to Geert Wilders, the Dutch right-wing populist leader, as a foundation of today’s civil society. And, it has been quite popular among American neoconservatives, like Steve Bannon.

At the same time, it has been flatly rejected by prominent Jews who say the term Judea-Christian is nothing other than a ‘fabled tradition does not exist, nor does the “Judeo-Christian ethic”…For Christianity, Jesus is central; in Judaism he does not figure even though he was a Jew.’

The notion of ‘Judeo-Christian’, putting aside its religious connotation, as the foundation of Western civility is rather arbitrary, if not ambiguous. Various Christian fundamentalists and self-proclaimed traditional Catholics have employed the ‘Judeo-Christian’ discourse to justify their backing of Israel, despite the term being neither eschatological nor doctrinal. Yet those who have cited the ‘Judeo-Christian’ tradition as the basis for US support of Israel, have likewise asserted the two nations are connected due to their ‘shared ideals and democratic institutions rooted in a Judeo-Christian worldview’, without elaborating on the true meaning of this statement.

Origins of the Term Judeo-Christian

In the US, the term ‘Judeo-Christian’ first appeared on 17 October 1821 in a letter by Alexander McCaul which referred to Jews who had converted to the Christian faith. It was used in a similar yet different way by Joseph Wolff in 1829 to describe a type of future Christian church that would also observe certain Jewish traditions in order to attract and convert Jews.

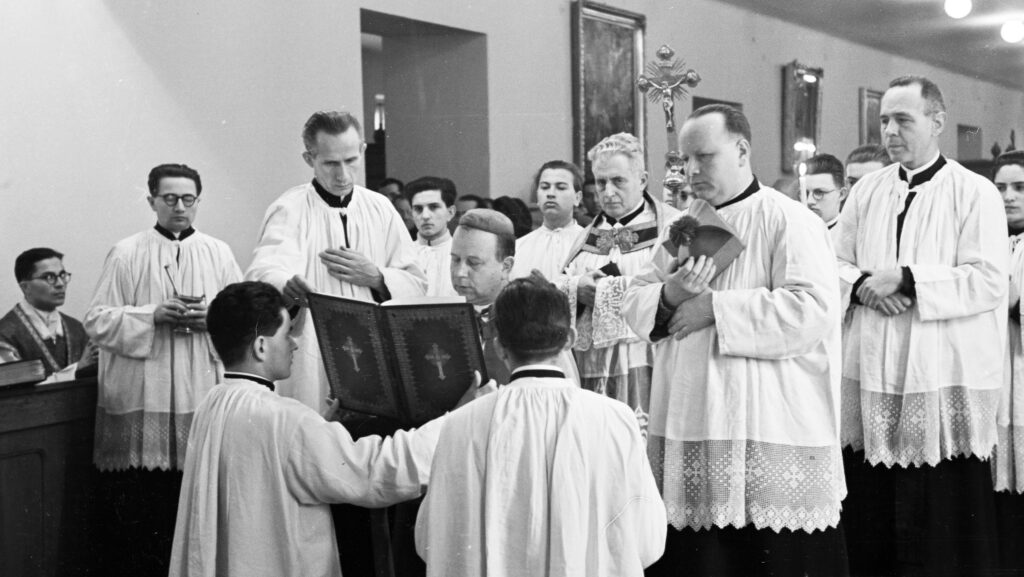

According to K. Healan Gaston, a professor of American history and religious ethics at Harvard Divinity School, the related term ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’ emerged in America during the 1930s when certain non-denominational Christians and certain mainline Protestant churches tried to produce a unified cultural identity to distinguish the US from fascism and communism then in the ascendent in Europe. In part, this was due to ‘Christian’ becoming an innuendo for fascism and anti-Semitism when the Catholic priest, dubbed the ‘Radio priest’, Father Charles Coughlin expressed public and constant sympathy for the regimes of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini as a solution to combat communism.

The term rose to even greater prominence during the Cold War, when then President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower, in his opposition to the atheistic doctrine of the Soviet Union said:

‘Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.

With us, of course, it is the Judeo-Christian concept but it must be a religion that all men are created equal.’

In 1970, it became associated with socio-political movements on the American Christian Right, especially with the Southern fundamentalists from the Bible Belt. We see this, for example with the Rev. Jerry Falwell and his Moral Majority, who called for a return to ‘Judeo-Christian values.’ Under the argument that such virtues were an American standard weakened by liberals, Falwell appealed for unconditional support for the State of Israel, which he saw as a sign of God’s hand moving in history.

In Europe, however, it was only at the end of the 19th century in Germany that ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’ was used in a clear and distinct way. According to the Jewish theologian Arthur Allen Cohen, Judeo-Christian’ was introduced by German Protestant theologians who, in their exegesis, sought to counteract Old Testament criticism—specifically that which came after the Enlightenment—which had challenged the Bible’s historicity, and questioned it as a book of divine revelation.

Yet even those German scholars argued that there was no real commonality between the terms ‘Judeo’ or ‘Christian.’ The emphasis, therefore, then began to fall on the hyphen between the two words, which was increasingly seen as the best way to show an apparent link between the two religions. In other words, the hyphen was used to join ‘Judeo’ and ‘Christian’ into a single two-part term which would thereby present both religions as being inherently one. In fact, as explained by James Loeffler, Professor of Jewish History at the University of Virginia, in his ‘The Problem With the “Judeo-Christian Tradition”’:

‘After centuries of Christian anti-Semitic persecution and philo-Semitic fantasies of Jewish conversion, many eyed the award of an honorary hyphen with suspicion.’

Religious Distinctions

The present-day phrase ‘Judeo-Christian’ is used to group the two religions together as if they were one, perhaps because of the moral points that both traditions share that are derived from the Decalogue.

Aside from the development of thought based on the Ten Commandments, or the assimilation of some ritualistic practices (such as circumcision), which were reluctantly observed by the early Christians, specifically by the Apostle St Paul (Galatians 5, 2-4), there has never been a direct link to Judaism as Christianity evolved and spread across the West. In fact, early Christianity had sought to distinguish itself from Judaism.

The Jews are, nevertheless, still expecting for the Messiah to come out of Zion. Our Christian faith, instead, affirms that He already came in the person of Jesus for the redemption of all peoples, not just Israel. Judaism rejects that Jesus is the Messiah, and thus the divine Son of God, even though He came to fulfil the Old Law. (Matthew 5, 17) Hence, the reason the Sanhedrin—the Jewish body politic—brought Him to the Governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, to be crucified for the crime of blasphemy since Jesus called God His Father. (Matthew 26, 57-68)

There is also a distinction, which many cannot see, between the Israelites of old and the present-day Jews. The former are a people united by familiar ethnic or religious beliefs, who descend from the Hebrew Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The latter are descendants of the former, who after the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD adopted the Talmud, which has no priesthood, and consequently ceased to practices the sacrificial rituals they were accustomed from the inception of receiving God’s Revelation. In other words, it is not so much as the acceptance of the Old Testament, in as much as a people whose religious observances contrast those of their forefathers.

The West’s roots, from a socio-historical viewpoint, are found in both Greek philosophy and Roman law as embraced and spread by the Catholic Church, as evidenced, for example, by the formation of the ius commune—a common legal system in Europe that remained in force until the era of national codifications, specifically with the Napoleonic Code of 1804.[1] I cannot be denied that there has been a combination of elements from the Jewish tradition of old and Christianity—but it would be inaccurate to wholly equate them. Even the Jewish philosopher Maimonides viewed Christianity as having a more positive function in world history because it brought a form of monotheism to the pagan world.

The exclusionary usage of ‘Judeo-Christian’ has tended to be one of neoconservative politicians who have positioned themselves as defenders of their respective nations. Their pretension is laying claim to laws and ethics based on ‘Judeo-Christian’ values, despite Jews essentially being excluded by states that claim a ‘Judeo-Christian’ foundation, such as when the English kingdom expelled all Jews from England in 1290 or when Jewish refugees were turned away by Canada, the US, and the UK during World War II.

The views expressed by our guest authors are theirs and do not necessarily represent the views of Hungarian Conservative.

[1] Andrea Drigani, Il Sense di un diritto comune: Gli aforismi giuridici di Dino Mugellano. Firenze: Libreria Editrice Fiorentina, 2016, 5.