This essay was originally published in Hungarian language and supported by Szent István Institute, a Hungarian non-profit organisation for Christian democracy.

Over and over again, we have seen great empires rise on the foundations of internal stability and innovation, spreading and devouring other communities, conquering the Hill of Might, and flying the flag of unity at the top. Then, the plagues come: plagues of comfort and arrogance that result in widespread moral decay and meaninglessness, leading to a sudden downfall in the end.

As Christians we may recognize such patterns not only as true for large communities—to us, this drama seems to be much more the fate of each human being. We receive our gifts and blessings for free, yet when we achieve success, we are filled with pride, starting to ignore the will of God and commit sins—then accept failure and humiliation as rightful consequences. It is at that point that we must make our most significant decisions: at the crossroads, we either step onto the path of repentance or that of arrogance. We either confess our disgrace, accept divine punishment dispensed out of love and let him raise our lives again, or we try to rise relying on our own strength, without obedience, and fall again.

This, however, is not a linear story of decline, as many hold, but a cyclical development of people and civilizations.

Maybe our beloved Europe is no different. It is in Europe that the first Christian civilization appeared,

with two competitive advantages compared to all other parts of the world: a strong purpose and social organization.

Both of them were necessary. Some parts of the world may have had better functioning societies, and there were also other cultures that also had universal missions, yet only Europe was able to combine moral order with a common purpose, which propelled development at an unprecedented pace. Of course, medieval and early modern societies were far from perfect—yet their compass was impeccable.

So what happened when we ‘reached the peak’? That was the time of pride and arrogance, when Europe dropped the faith and resorted to violence. While Christianity and its achievements spread throughout the world, they came with an unprecedented bloodshed in the context of colonization, based on a conviction of European supremacy. On our continent, the result of the Reformation was not a moral cleansing of institutions and of the general way of life, but an endless war over doctrines. The first sign of Europe going astray was the Enlightenment that emphasized the forgotten values of reason, equality and progress, which did not, however, build on the foundations of Christ anymore, but appealed to the purported benignity of the human person, ‘exceeding’—or abandoning—its origins. Europe did not convert—she revolted like a child, while proudly proclaiming her adulthood.

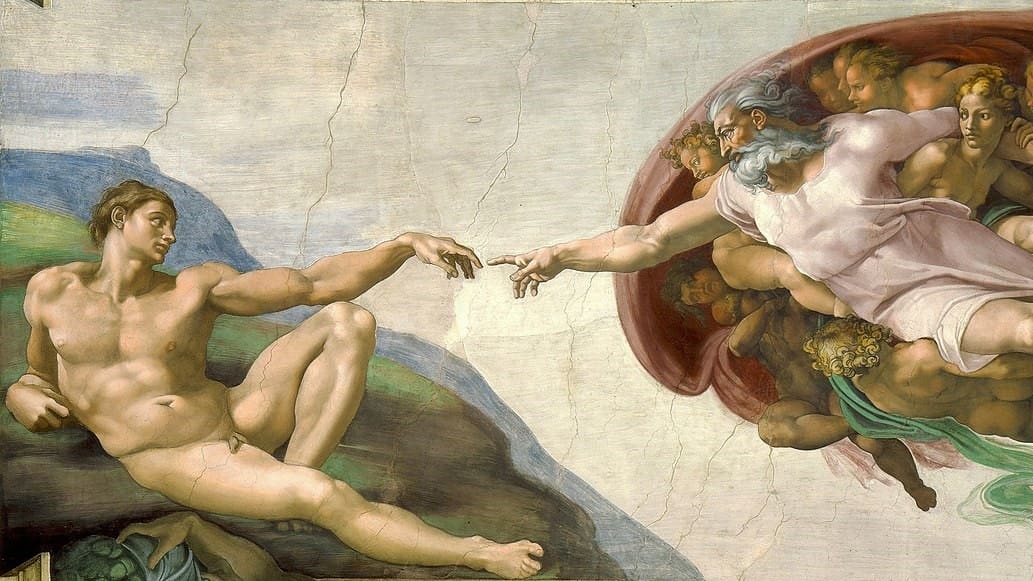

Europe after the Enlightenment was not the same anymore. She inherited the idealism of Christianity and the values that organized its societies, as well as the anthropology that raised the human person to a higher pedestal than any other culture, as the ‘image and likeliness of God’. This is the reason why, after ‘dethroning’ God, we have raised ourselves as the highest ideal in modern secular humanism, and our well-being to the highest purpose of civilization.

This led to the triumph of individualism and utilitarianism,

which transformed Europe’s economic and power structures. After the Middle Ages, the salvation-centred culture of which was full of cruelty and hypocrisy, the other extreme of material idolatry took hold of Europe behind the mask of humanity and freedom.

As time passed, it became ever clearer that prosperity and formal institutions are not enough to keep societies together—we need spiritual binders, culture and values. But since a profound Christian renewal was out of the question, particular values of Christianity were reshaped through ideologies, reconciling a thought of human omnipotence with the concept of moral universalism. In the meantime, as traditional communities started to decay, the human person satisfied his natural desire for connection through modern tribalism. That is why nations and social classes—both of them having biblical origins— strived for an exclusive role, to shape societies in extreme forms.

However, when humans meet their limitations and the consequences of their actions, there remains, again, a choice. This phase in European history arrived when two world wars and the rise of totalitarian regimes exposed the limits of rationalism and voluntarism deprived of objective moral standards. At the crossroads, Europe seemed to step on the right path—early Christian Democrats proposed limitations of power based on human dignity and justice; building post-war economies keeping a balance between freedom and solidarity; and paving the way for a Europe based on subsidiarity and peaceful cooperation among nations.

A historic opportunity to return to its Christian roots in the framework of a modern democratic society opened up for Europe. However, the demand for the ‘Christian element’ decreased over time, as something viewed as unnecessary or just a shadow of the past. Neither the people nor the elite stood up for the Christian heritage when the foundations of an ever closer union were laid, and the name of God appeared nowhere in the draft Constitution or the Treaties. It became clear that Europe was not able to make peace with its history, but remained in denial regarding its origins.

Today, Europe is keener on promoting values of multiculturalism or the sexual revolution than the values of Christianity.

Postmodern societies are navel-gazing. They serve no morally higher purpose, and have no past or future; they focus on providing freedom and wealth, which were originally viewed as tools to build a more virtuous society, but are now the end goal of governance and society. This phenomenon has its roots in the anthropological nihilism of the 20th century, which offered the most reasonable alternative to faith in Creation since the Enlightenment, and which provides strong fundamentals to modern individualism.

What social liberalism, the ideology that defeated all others, cannot handle is the aspect of human nature that—since we are created and have limitations—humans always look for a cause beyond themselves. Though hedonism can temporarily cover our inherent desire to serve, yet it can never fulfil the lack of personal and collective purpose. Civilizations that reach a certain level of prosperity will start desperately seeking to establish their own relevance—moral justifications for what they do and why it is right to extract resources from others. Deep down, however, an existential fear emerges due to a lack of a reason to sustain civilization at all.

In Europe, amidst a civilizational crisis, a new narrative is unfolding: one of unlimited progress that aims to create a new order based on modern ideas, denying the existence of timeless values. Its characteristics include historical guilt and overcompensation, detaching democracies from moral standards that created them (see the Böckenförde paradox), and sacred reverence of values stripped of their original meaning that turn postmodern politics into crusades over identity issues. As a reaction, traditionalists have turned to the past, building on the instinctive fears of the general population, and some leaders now follow flawed ideals such as feudalism and totalitarianism as a means of rejecting progressive agendas. The escalation of political extremes that mutually fuel each other can be observed throughout Europe, and genuine Christian thought is less and less prevalent.

Today, Europe is much further from unity than it seems, with deep cultural and moral divides and a lack of shared purpose. There are no effective social and political models for solving the issues of the 21st century, including demographic decline, political polarization, the worsening of social prospects for young people, environmental unsustainability or permanent conflicts between Western countries and Central and Eastern Europe.

What should we do now? Above all, Europe needs discernment: the discerning of its inability to rise solely by human endeavour. Recognizing that one thing is necessary for a meaningful change. And it is not political will or centralization of power, but

the heartfelt repentance of nations.

Repentance is not something that the secular political establishment could implement; it can only inhibit or give place to everyday ministry. However, there are certain tools which the state may use to support a renewal of European societies, drawing from Christian thought and tradition.

First, we have to rethink our relationship with political power. Since the philosophers of the late Middle Ages it has been inherent to European political thought that power, as a tool of humans to lead other humans, must be subjected to objective limitations through institutions and moral principles. This flows as well from the anthropology of the Bible itself, as power—just like everything else under God’s creation— is ordained for specific purposes. In this case, the service of common good. Even the most tyrannical systems in Europe have recalled different moral justifications for their actions, as they knew that without an allusion to the common good they would have no legitimacy.

In Europe the focus of political debates has shifted towards who possesses power in certain domains, instead of what is the purpose of government, and how political power can be directed towards the common good. The principle of subsidiarity shall be brought to the frontline to rethink our systems of checks and balances in Europe. Nation-states, as well as European institutions should show political self-restraint, aiming to find common causes through which the future of Europe may be advanced.

Then, we have to enhance innovation in science, culture and the political sphere as well. Today, the dominant paradigm would tell us that competition, debate and social development are the result of relativism, but it is quite the opposite. In Europe, the premise of an objective truth and the existence of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ as adversaries, above the subjective reality of each person, which dates back to even before Christ, was the reason why science and reasoning could unfold as methods for finding what is ‘true’ and what is ‘good’ in society. Truth, as such, is not defined by humans, but by God, and humans need to constantly seek this truth. The constant fighting over the monopoly of interpreting the truth has led first to war, then to debates that advanced moral, philosophical, and political thinking. Over time, Europe has developed its ability of dialectical thinking, from politics to science, institutionalizing its social development, and constantly balancing pluralism and morality.

In the same way, ideas and inventions that changed the world came from a desire to create something good—including, of course, self-interest. Democracy itself is also largely a result of this ‘tolerant idealism’ that allows values and ideas to peacefully clash with one another.

Thus, relativism is not a friend, but an opponent of a good society, whereas searching for truth supports innovations.

Europe in the 21st century, however, has become an echo chamber, a place of extremes and intolerance instead of creative ideas and constructive debates in search of the truth. We need to rethink how innovations can be supported in contemporary Europe in politics, as well as in culture, and in scientific and economic life.

Third, we need to restore the right anthropology, the right image of ourselves. Each civilization and each structure relies on some sort of anthropology on which the norms and directions of its functioning are based. What Christianity has given to the world is humans viewing themselves as the ‘image and likeliness of God’, prone to mistakes and iniquity, yet able to defeat evil with the power of love. Humans do not live merely for themselves or for a larger collective, but for the glory of their Creator, and experience fulfilment through interpersonal connections.

This idea of the human person is mirrored in the modern concept of human dignity, as well as in the unconditional respect for human life—values that are subject to grave violations in today’s world. Europe should rely on this anthropology, embracing and protecting the image of the created person, and supporting its dignity, as well as its natural communities in the 21st century.

This is not a task for one single party or nation. In all of Europe, we need to start reshaping the social patterns of thinking, and persistently hold up these values as the alternative in the long term. Europe has lost its way, being without a purpose, and forgot about her own heritage, the fruits of which she still enjoys, though the consequences of defiance will show; it is only a matter of time.

Limiting the power of the state for the sake of the common good, social development through seeking justice, and protecting the dignity of the human person created in the image of God are still remarkable virtues of our civilization that the world needs so much, an example to be followed, and which can give a new purpose to Europe in the 21st century. These spiritual battles are not fought with hard power, but rather through the hearts, minds and souls of each and every one of us.