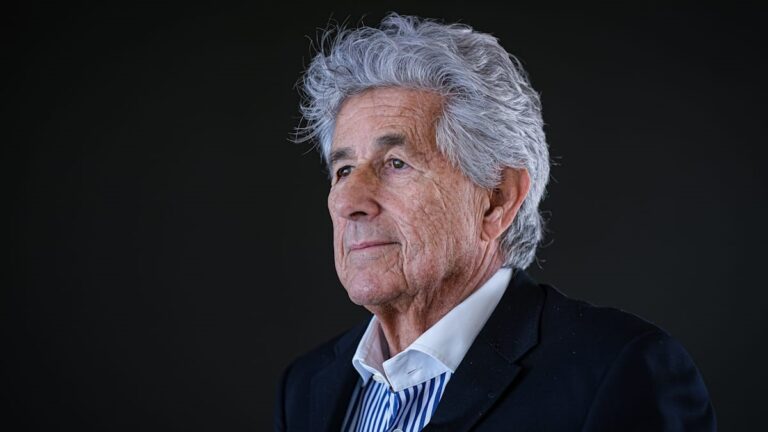

On the sidelines of the MCC conference on the future of publishing held between 25 and 26 January in Budapest, Hungarian Conservative interviewed Rodrigo Ballester, head of the Centre of European Studies at MCC about his views on publishing and the digital revolution.

You are the head of European Studies at MCC. How would you describe your job there?

My job entails teaching, publishing, learning and also doing research on the European Union from an angle that is not the usual one. The thinking in the European Union is very homogenous, and here at MCC we try to look things from another angle.

You are relatively active on Twitter, and you have often stood up for the positions of the Hungarian government on the platform. How was this received by your colleagues and friends?

I started my account when I was already here, I have few followers from my ‘previous’ life as an EU official. Yet, I publish a lot in the press, in the French, Spanish, English speaking press—and also in the Hungarian press (in translated as I unfortunately don’t speak your language properly). There is an impact there, because it is obviously rare for a former EU civil servant to come to Hungary first of all, and also to come to Hungary and defend publicly the vast majority of the positions that the current government is taking. The reason why I do it is because for me, their vision of Europe is much closer to the original vision of the European Union, the way we had it seventy years ago, before the Treaty of Maastricht. So my positions are so far taken with some courtesy but also with coldness, since they are considered to be controversial and ‘deviant’ in the EU and in Brussels. So sometimes you have to pay a social price for taking a public stand. In my case, so far it is bearable, but when I have an exchange with former colleagues or friends with opposite views, I come to the conclusion that the hostility towards Hungarians has never been as high as now. It has become something visceral and irrational. It is difficult to formulate political opinions based on rational arguments, things have become much more emotional.

How do you think the new regulations proposed by the EU would affect journalistic freedom?

What I am most worried about is pluralism. Whether all journalists, including the conservative ones, are going to still be able to speak. What the EU is doing in the field of media is very telling, because it gives us very good examples on what the EU can bring as a positive added value, and also a very negative one. For example I think that what they did in 2019, reforming the copyright directive, goes in the right direction. It is a way to make sure that the big platforms such as Google, Apple and other big companies are not able to cannibalise published content. And they don’t make millions and billions from the work of others. So, this is a step in the right direction. Because ensuring the business model and profitability of publishers and editors is also a way to keep the press independent. I am much less positive, actually very negative on the new proposal by the Commission called the European Media Freedom Act. It is a proposal so far, but it comes with very worrying ideas. Because it is an attempt to centralise competences the European does not even have. I think this is the biggest weakness currently of the EU, that they are looking to centralise everything, whether they have the competences or not, whether they have the mandate or not. If you look at this proposal, it is justified on a legal basis that has nothing to do with media freedom.

Brussels has no mandate to decide what editors should do and what they should not,

neither to create a new European body that is going to enforce and monitor this legislation. I believe that this is a step in the wrong direction. And the first question that comes to my mind is whether they have to competence to do this: the answer is no. . The second question is whether it is a good idea or not, and I do not think it is. So, when you implement a bad idea without the mandate to do that, we have a problem.

You used to be part of the cabinet of then European Commissioner Tibor Navracsics. At the time you proposed introducing media studies to elementary and secondary schools in the EU.

This was a recommendation because, thank God, the EU does not have competences in the field of education, although, bizarrely when it comes to the Hungarian law on the protection of minors, they found some legal competences that they do not have. Again. We thought that media literacy is very important, because the way youngsters today read newspapers—if they ever read them,—is very different. Today with all the culture of clickbait and new business models, that are basically monetising your attention, there is a potential of totally distorting information. Some youngsters are extremely impressionable. And the context in which we proposed the idea was about terrorist radicalisation. How for example terrorists from Syria could radicalise European youngsters and convinced them their cause is just. So, it is important to teach everyone, especially young people, that sometimes information comes with strings attached or that it is simply not information. That we also need to look at the colours and the funding of media outlets . We also have to teach them how to balance different sources. That they should read newspapers from a range of different political backgrounds that look at things from many different perspectives. Especially now with the algorithm culture, young people run the risk of ending up in an echo chamber. This happens a lot on social media. They start to believe that their micro bubble represents the rest of society. The danger is that they are never exposed to different views, and often they are offended if they are.

This radicalises and completely atomises society.

It is a very complex issue. Of course, at university, communications students learn about that, however, by then it is too little too late. And media literacy should not only be taught to media students, but to everybody.

Do you think there is such a thing as absolute objectivity in media? Does journalistic freedom really exist?

I do believe that there is no pure objectivity. We all have some conscious or unconscious biases and journalists are certainly not an exemption. The best way to combat this is to have newspapers from all sides on equal footing, which is not the case today. In Western Europe especially, where the press is clearly dominated by left-leaning journalism. Those outlets should of course exist, but not only them. There should be a balance, not an hegemony on neither sides. As to newspapers that report on the European Union, for instance, after spending 17 years in Brussels, I do not know a single one that is Euro-critic. They are all shaped in the same mould. And that is a problem. Also the fact that newspapers are less profitable than before is of course a problem for the editors and publishers, but also for the journalists, because they are now in a situation of economic precarity that forces them to sacrifice a bit of their own independence. And also to adopt a tabloid style, a clickbait type of journalism. That is to the detriment of the quality of journalism in general, also to the detriment of the democratic debate. That is why it important to protect business models that allow everyone to make money in the field of journalism without public subsidies for example.

Youngsters now get a large portion of their information from social media, not newspapers. Do you think these platforms kill newspaper and print, or can they co-exist?

I would rather say that, in general, The digital world is killing the analogue world. And that applies to the press as well. But the most relevant question is: are these platforms killing the editors’ business? It seems so, and that is very dangerous. Because at the moment, most people read newspapers on Google or Facebook and — those platforms are basically cannibalising the content of journalists and editors. This means that we will go in a direction where there are only five or six platforms in the world that will decide what will be read and what will not. That for me is an Orwellian nightmare. The question is not whether digital will kill paper, that is already happening. My real problem is the possibility of real journalists and real editors dying out, and all the outsourcing of information being given to big platforms. A scary, but very realistic perspective.