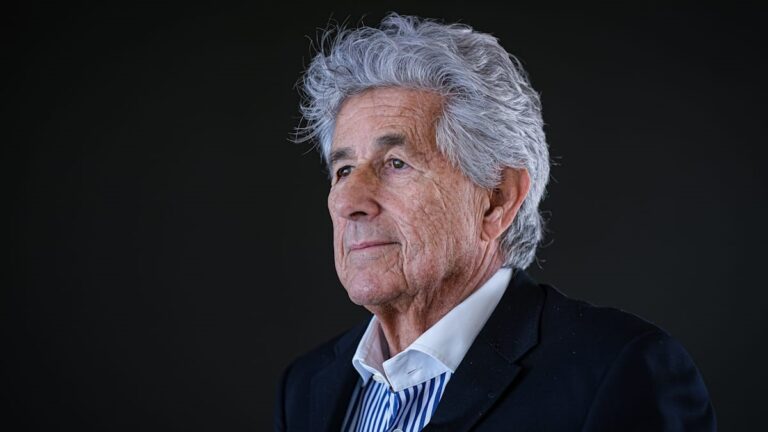

Mr János Bóka is the State Secretary for EU Affairs of the Ministry of Justice of Hungary and the Prime Minister’s EU sherpa. Mr Bóka received his J.D. and his Ph.D. in law from the University of Szeged (Hungary) and an M.A. in European Integration and Development from VUB (Belgium). Previously, he served as a senior legal advisor focusing on EU law, private international law, cross-border insolvency and consumer protection at the Curia (Supreme Court of Hungary) and as the director of the Hungarian Academy of Justice. He taught EU law at various universities.

Last April, already aware of the results of the Hungarian elections, the European Commission initiated the rule of law conditionality mechanism against Hungary. From a political point of view, Hungary had already been carrying a very heavily burdened ‘procedural package’. Last autumn, however, there seemed to be light at the end of the tunnel and in December, the Hungarian government envisaged that the sky over Hungary might be cleared by this March. It’s March, so the question arises: where do we stand now, exactly what procedures are underway against Hungary?

As of today, there are at least four procedures that can be labelled as rule of law related procedures. Some involve access to EU resources, and some do not. If we look at the chronological order, it is the so-called ‘Article 7’ procedure that was first to be launched against Hungary, a purely political procedure initiated by the European Parliament. This procedure has been going on for five years now, gradually losing all focus and direction. However, this has no direct impact on the EU funds available to Hungary. The next procedure in chronological order is the so-called ‘conditionality procedure’. Indeed, as you recalled, the president of the European Commission announced this a few days after the Hungarian parliamentary elections last April. Measures adopted by the Council of the European Union in this procedure last December suspended access to certain EU funds.

For the suspension to be lifted, Hungary proposed measures that are now being implemented and will be evaluated by the Commission and subsequently by the Council.

In parallel, another process is taking place, which is not a procedure in the strict sense of the word, but rather the implementation of commitments made within the framework of Hungary’s Recovery and Resilience Plan. These commitments include but are not limited to the measures proposed by Hungary in the conditionality procedure.

Are these commitments the so-called milestones?

Yes. Among these milestones, the European Commission insisted on a series of so-called ‘super milestones’. Fulfilment of the latter category is a prerequisite for submitting any payment request under the Recovery and Resilinece Fund. And as I mentioned, there is a fourth procedure. This requires compliance with the so-called Horizontal Enabling Conditions blocking the cohesion funds necessary for the implementation of operational programmes under the seven-year financial framework for Hungary. Some conditions block virtually all the cohesion resources, while some conditions affect only funds for certain limited areas.

What can Hungary do in the web of these intertwined procedures?

We must manage these parallel procedures in such a way that, at the end of the day, Hungarian citizens can access the resources they are entitled to. Politically, this is not an easy balancing act. From our point of view, these procedures should not have started against Hungary in the first place. The launch of the Article 7 procedure by the European Parliament was a clear political act with purely political objectives. The legal prerequisites for the initiation of the conditionality procedure have not been met either. We also believe that we comply with the horizontal enabling conditions where the Commission is raising objections. The political message of our decision to nevertheless engage in sincere cooperation with the EU institutions is not always fully appreciated.

We have done so for the sake of European unity and to prevent further escalation within the framework of European integration

in a particularly challenging security and geopolitical environment. It is in this context that our commitments in all procedures must be interpreted. The Commission seems to take a different approach. It is to be noted, however, that the position of the Council of the European Union seems to be more nuanced that of the Commission.

You said, ‘at the end of the day’. Which day can we mark on the calendar?

We are working with the Commission to address their concerns. We submitted several initiatives, measures, and draft legislation to the European Commission for evaluation and we are in the process of implementing agreed measures. This is a protracted process and I believe that at this point it is not possible to give a reasonable estimate of when it will actually be completed. Nevertheless, I am convinced that it could be concluded in the first half of the year – if we only look at the technical side of the process.

The concept of the rule of law presupposes that basically, lawyers negotiate with lawyers. However, based on the political noise and the extremities of the media coverage surrounding this topic, we can reach different conclusions. Is it a legal or a political process?

This process has a political side as well. To be a bit more specific, all the procedures initiated against Hungary have strong but different political aspects. There are procedures—such as the Article 7 procedure—where legal and technical boundaries and limitations can hardly be identified; in the case of such procedures, the predominantly political nature is crystal clear. And although the technical and legal constraints are much stronger in the case of the conditionality procedure and of the fulfilment of the abovementioned super milestones, there are fundamental political considerations in these procedures too.

Would you elaborate on that?

Just as the initiation of these proceedings was determined by political considerations, their conclusion will also depend on political will. In these procedures, the best Hungary can do is to create the legal and technical conditions for closure. We believe that this already happened last December in the case of the conditionality procedure. In the same way, during the fulfilment of the super milestones, we will also be close to the deadlines we have set for ourselves. But

let us have no illusions: in the end, it will be the political decision of the institutions and the member states that will put an end to this procedure.

Looking at the challenges the European Union faces today, political considerations should primarily work towards the acceleration of the procedures with the aim of closing them as soon as technically and legally possible. Obviously, this view is not shared by all stakeholders.

Good faith dictates that we have reason to trust that the way to the suspended resources leads through the fulfilment of the so-called (super) milestones. These are included in the annex of the Commission’s evaluation attached to the Hungarian Recovery and Resilience Plan. The negotiations between the Hungarian government and the European Commission were around these specific milestones. And yet, by raising the issue of the Erasmus+ and Horizon Europe EU programmes, the European Commission seems to have unilaterally modified the terms of the deal—just as Darth Vader did when he had Han Solo frozen in the movie The Empire Strikes Back. What are the prospects, can we expect similar additional conditions? If so, how is the Hungarian government preparing for such and similar situations?

During the proceedings, our experience has been that there is an established culture of introducing additional conditions in Brussels. I think that this practice stems from the fact that the Commission is not entirely certain what political goals it wants to achieve with these procedures. In a situation where the Commission’s negotiators do not receive in advance clear political guidance from the College of Commissioners, the services obviously will have to employ a tactic of keeping the procedure open until a political decision is made to close it.

When the European Commission meets a bona fide negotiator like Hungary, doing everything reasonable to meet the previously communicated expectations, the only way to maintain the process is to make more and more demands.

I believe that this is a natural consequence of the political uncertainties within the Commission. We must deal with it somehow. So far, the Hungarian government has approached this issue by trying to respond to all expectations in accordance with the requirement of sincere cooperation.

As a lawyer, how do you evaluate the milestones system and the Commission’s method of implementation in this regard?

From the point of view of the legal system of the European Union, the procedures in which Hungary is involved pose a series of problems. Perhaps the most important problem arises around the purpose of the procedures. In principle, the purpose of the conditionality procedure would be to protect the financial interests of the Union. By nature, the conditionality procedure is not a rule of law procedure. Its scope extends to rule of law related concerns only if and to the extent they have an impact on the EU’s budgetary interests. Regarding the concerns raised,

it has been disputed from the very beginning whether they had an impact on the budgetary interests of the European Union at all.

In the case of the additional expectations you mentioned, no connection with the Union’s budgetary interests can be demonstrated. The other problem with these procedures arises in connection with the principle of sincere cooperation. According to our interpretation, these procedures should be about the implementation of previously agreed commitments and the verification thereof. We see this as a closed process, where a finite number of concerns must be addressed. By definition, the implementation of these commitments results in the closure of the process.

Are you sure that the European Commission views this negotiation process in the same way?

From my point of view, the Commission’s approach is ambiguous but it seems more inclined to endorse an open-ended process, where the goal is to achieve some vaguely defined political result over and above specific commitments and milestones. And as long as this goal is not achieved, this procedure mustn’t be closed regardless of the implementation status of the agreed commitments.

You have mentioned your concerns about the process. Do you also have material concerns as well?

Yes. In connection with the interpretation or enforcement of the undertakings, the Commission pays relatively little attention to the constitutional arrangements, national traditions, legislative practice, legislative style, and operational characteristics of the legal system and institutions of the member states. It sets expectations that simply cannot be implemented in the given political and legal culture. And even if the implementation is possible, the European Commission is reluctant to give the Member States the flexibility that would allow them to develop solutions that are coherent with their constitutional and legal systems and are feasible in practice.

Delegations from the European Parliament are coming to Hungary from time to time only to have devastating reports prepared as a result. How do you assess the role, influence, and performance of the European Parliament in this rule of law debate?

The European Parliament has always been part of the problem and not the solution in the context of the rule of law-related procedures. The European Parliament is a purely political institution considering all procedures from an exclusively political point of view—regardless of legal grounds and factual bases.

In these procedures, the European Parliament is guided solely by political goals.

This is the reason why the European Parliament—including senior officials of the EP—makes statements and starts initiatives with the sole purpose to further burden these procedures, make their conclusion even more difficult, and further complicate the already complicated legal and political situation.

What are your predictions for the behaviour of the European Parliament as the elections approach?

I expect that the attitude of both the European Parliament as a whole and the individual members will become more and more extreme. I believe that it is the fundamental objective of the European Parliament that these procedures do not end at all but at least certainly not until after the EP elections in 2024. The EP has made it clear that it is against Hungary getting access to EU funds under the current government. To reach this goal, the EP will use all means at its disposal.

Is Hungary ready to meet the challenge?

I believe that the European Parliament does not consider the issues in question to be legal issues. This is an open political confrontation between an EU institution and an EU member state. This is a regrettable situation that is difficult to reconcile with the text and spirit of the EU treaties. It is not in our interest to escalate the institutional conflict but political attacks cannot be left unanswered.

In your opinion, would this procedure have been initiated against Hungary if there was a European Commission in office that sees itself as the guardian of the treaties and not as a political actor flexing its muscles?

The European Commission and the European Parliament locked each other in a vicious cycle that has serious repercussions for a member state. The current Commission sees itself as a political body and has ambitions far beyond its original role as the guardian of the treaties. This self-perception allows room for political considerations beyond the provisions of the founding treaties. This also made the Commission vulnerable to external political pressures because its activities are now subject to political debate. On the other hand,

the European Parliament has been keeping the European Commission under constant pressure

to take an extremely tough position on Hungary. And an openly political European Commission is no longer in a position to find either the strength or the will to resist the pressure of the European Parliament.

You said that Hungary is a bona fide partner of the European Commission. Since last fall, legislative proposals aimed at ‘fine-tuning’ the legal system have been published and adopted from time to time. How is this process going now? In which areas has the legislation agreed upon with the European Commission already entered into force, and in which areas can further legislative developments be expected?

The most far-reaching change was the creation of a new, previously unknown authority. This is the Integrity Authority. This has no precedent in the Hungarian legal system. There are European examples that we have considered, though, for example from Slovenia and Italy. We tried to create an authority that has added value to the Hungarian legal system and can contribute to making the protection of the financial interests of the EU more effective. In addition, we had to effect changes to a relatively wide range of legislation, from the public procurement law to the assets declaration system and the criminal procedure law, etc. We have amended several laws while making sure that we preserve the coherence of the legal system. Negotiations are still ongoing with the European Commission in a number of areas.

Has the legislator drawn a red line in terms of what the subject areas are that cannot be affected by this huge legislative reform?

Our guiding principle in this process is that the constitutional order defined by the Basic Law cannot be altered by these amendments. We will not propose any regulations that adversely affect the coherence of the legal order or the constitutional balance of the institutions.

You stated that the legislation adopted could provide real added value to the Hungarian legal system. Can the same logic apply to the EU as a whole?

I believe that not only can it apply, but it must apply. I believe that the Integrity Authority, or the modified system of our asset declarations can serve as an example for those member states where such institutions do not exist. And

it should also serve as an example for the EU institutions,

where the rules are known to be more lenient as regards asset declarations, conflict of interest, and lobbying.

Last December Hungary has been sued by the European Commission before the European Court of Justice regarding the Hungarian Child Protection Act. At the beginning of March, we learned that Justice Minister Judit Varga submitted a counterclaim to the forum in this case. Could you summarise what the underlying procedure is about and what the key points of the Hungarian argument are?

The Hungarian argument is that our regulations in fact enhance child protection and do not deprive anyone of any rights. Actually, they are there to ensure the exercise of certain rights. To this end, they aim at ensuring that parents have the right to play a decisive role in deciding what sexual content— whether it is information, education, or other content—reaches their minor children. To protect the best interests of children, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also guarantees this right to parents. In addition, it stipulates as an obligation that

the child must be provided with appropriate protection depending on and in accordance with their age, and the Hungarian regulation serves this purpose regarding sexual content.

It is a fundamental misunderstanding to attribute a different purpose or content to this regulation. We believe that this regulation is not in conflict with EU law. Furthermore, we believe that this regulation applies to situations where the European Union has no regulatory competences. Accordingly, member states are the only ones entitled to regulate how and under what conditions children can access such content.

The procedure is currently before the European Court of Justice, which is known for its activist approach when it comes to issues that otherwise fall under the competence of the member states. According to press reports, various NGOs expect a growing number of member states to intervene in the lawsuit. Belgium is already on board. What outcome does the Ministry of Justice predict for this lawsuit? Can this procedure affect the procedures we discussed above?

As a lawyer, I can only say that from a legal point of view, the Hungarian case is solid. The Court of Justice of the European Union will have to carefully examine our arguments. At the same time, this case has become a political flagship project as well.

The member states’ interventions in this procedure must be understood in a political not a legal context.

That being said, political messages are not relevant in terms of the legal outcome of the litigation. But this is supposed to work the other way around as well: we have not made any commitments related to our child protection law in the framework of the conditionality procedure, therefore the infringement procedure must not have any impact on its closure.