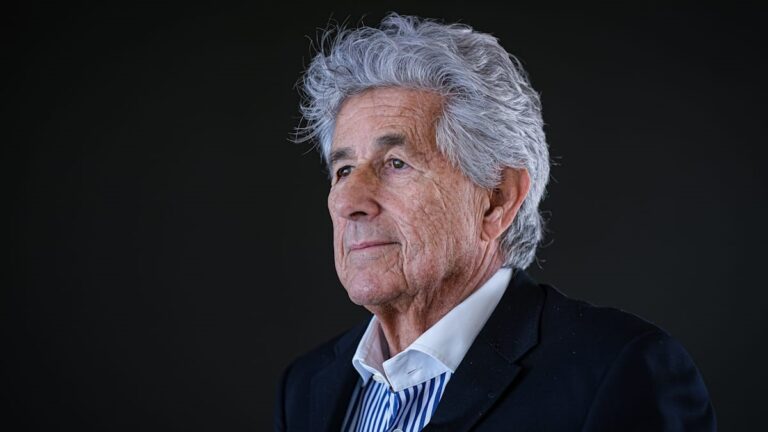

Prof. Dr Csaba Polgár is the Director General and the Head of the Center of Radiotherapy at the National Institute of Oncology in Budapest, Hungary, where he has been practicing as a radiation oncologist for over two decades. His main research activity is focused on the radiotherapy of breast carcinoma, furthermore he was one of the pioneers implementing the new treatment paradigm of accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) in the management of early-stage breast cancer. Based on his scientific work in the field of breast cancer radiotherapy and brachytherapy he became an internationally recognized expert. Professor Polgár also holds prominent positions in both national and international professional societies. He is a university professor and the Chair of the Department of Oncology of Semmelweis University in Budapest and frequently speaks at national and international conferences.

’The OECD published devastating data on Hungary’ — such and similar headlines appeared in the left-wing media a few weeks ago, when the OECD’s annual report revealed that cancer-related morbidity and mortality figures in Hungary are not only above the EU average, but Hungary is in the worst place in the EU. Is what is happening at home really a tragedy, or is the picture more nuanced?

This cancer profile is published by the OECD every year. There is nothing new here. It should be known that, in recent decades, Hungary has been consistently in first place in terms of cancer deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. This process has its roots in the 1950s, when Hungary was roughly at the same level as Denmark in terms of cancer deaths. After that, in the decades leading up to the fall of communism, the gap began to widen sharply. It should be noted that the same applies to all Eastern European countries belonging to the so-called post-Soviet bloc. In the meantime, however, Hungary is in a privileged position because, as I used to say, Hungary is the ‘westernmost country in the East‘ having good statistics.

What do you mean by that?

At the National Institute of Oncology, where we are now sitting, we have been managing the National Cancer Registry regulated by a government decree adopted in 1999. This is a so-called national cancer registry, which is a population-level cancer registry. It is the responsibility of the National Institute of Oncology to collect the so-called incidence data, i.e. the newly discovered cancer cases every year. Mortality rates published by the KSH are also entered in the same place. Thus, until recently, we were able to authentically publish the annual incidence and mortality data.

Is this exceptional?

In contrast to this solution, a significant number of EU countries either have provincial registers and, based on those, countries aggregate the provinces’ data. Or it is GLOBOCAN that determines the data based on estimates—this is how it works in many European countries located to the east and south of us. As a result, what can be seen in the country profile report is that Hungary is the first among the top ten countries, which by the way only include countries belonging to the former Eastern Bloc—except for Denmark, which happens to be seventh So, the fact is that the cancer situation in Central and Eastern Europe is bad and sad, and we are trying to cope with our burdened legacy. However,

Hungary’s first place is also due to the fact that Hungary provides accurate statistics.

We heard about similar methodological discrepancies in the case of COVID, right?

This situation is indeed similar to the one we experienced during the coronavirus pandemic. In the case of the latter, Hungary also reported every Covid-positive patient who died of anything as a Covid death. In doing so, Hungary provided objective, non-manipulable statistics. In contrast, several countries only reported deaths attributable to COVID-19 when the cause of death was clearly COVID-19. Of course, this has resulted in the fact that on paper, there were significantly more COVID-19 deaths in Hungary than, say, in Slovakia. So, on the one hand, this story indeed has a methodological aspect, but on the other hand, it is undeniable that Hungary and Central Europe are in a bad position.

The readers have been hearing about this for a long time…

It is a sad situation indeed, but it’s nothing new., The press could report this every year. However, what is much more important are the trends. What is also not highlighted enough, but is included in the OECD cancer profile you cited here, is that in the last ten years, i.e. between 2011 and 2019, male cancer deaths in Hungary decreased by 11 per cent, and female cancer deaths by 6 per cent. Similar trends can be seen across the EU, but in Hungary, this number is a little higher.

Simply put—we started closing the gap.

Furthermore, which is very important, and few people know, but it also clearly follows from the data of the cancer registry, that until the years before COVID, 75,000 cancer patients were diagnosed in Hungary every year. This number increased by almost 9,000 in about ten years—from 66,000 to 75,000. During the same period, cancer deaths stagnated at 32-33 thousand. Consequently, while annually we faced a significant number of new cancer cases, we have lost the same number of Hungarian citizens as 15 years ago. So, the chances of recovery from cancer have improved significantly in Hungary in the last ten years.

What is the reason for this?

Diseases are recognised earlier, screenings and therapies are more effective, access to therapies is better—survival results in Hungary have improved by roughly 11 per cent. All I want to say is that this problem should be viewed in its entirety. But to add another thing, I would cite another statistical number, which is mentioned less often. It is the so-called Mortality Incidence Rate Ratio.

Is it possible to set up a ranking in this, too?

Yes, and it gives a much more realistic picture. It provides a population-based indicator of survival. In this ranking, we are right in the middle of the forty European countries, twenty-first. This is not a triumph either, but we are where we belong in Europe according to our economic development. The Scandinavian countries are naturally at the forefront; however, if we look at the twenty-one Eastern European countries, we are in the 5th position among them. The reasons why this unfavourable statistical situation arose are also included in the cancer report.

Please explain.

These causes can mostly be identified outside the healthcare system.

The five most important cancer risk factors are smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, air pollution and low rates of HPV vaccination.

Keeping these five factors in mind can significantly reduce the risk of cancer. Hungary ranks worse than the European average in terms of smoking, obesity, alcohol consumption and air pollution. In the case of only one thing can we be relatively satisfied: the HPV vaccination rate is over 80 per cent for girls. This is the only aspect in which we score better than the European average in terms of primary prevention.

What follows from this?

It is, of course, important that we establish additional therapy centres, install CTs, PET-CTs, MRs, and introduce robotic surgery, as we have done over the past thirty years. In other words, it is of utmost importance that therapy and diagnostics develop, so that targeted therapies become possible, and we can provide a corresponding molecular pathological diagnosis. But if we want to tendentiously reduce the burden of cancer on the societal level, that is not the territory of the health sector, but a common project that includes overall societal and individual responsibility.

Where are the boundaries of individual and state-level responsibility?

As I said, we need to reduce the number of incidents by keeping these five risk factors in mind. However, it is easy to see that the Ministry of Health, or the department responsible for this policy area, cannot reduce these risks on its own. Of course, the state has a role to play in this: the introduction and financing of screening examination campaigns, the promotion of health programmes in which we focus on the healthy population, are tasks that cannot be spared.

It is necessary to draw the individual’s attention to the dangers of smoking, encourage them to quit smoking, and that it is healthy to have compulsory physical education classes.

Does the Hungarian government have a concept for this?

This is a complex task for which there has been a plan for a long time, and it is called the National Cancer Control Programme. Its last edition was published in the summer of 2018, which will be five years old this year. This is an ‘up-to-date‘ programme about prevention, screening, and includes—among various other things—early diagnosis, therapeutic methods, rehabilitation, and social education. But this also includes optimising the structure of the national oncology care system and monitoring. It is a complex system with the objective of reducing cancer incidence and cancer-related mortality and to improve the quality of life of patients suffering from cancer. The programme uses a system of tools based on scientific evidence.

Can this system be judged according to standards, or is this a country-specific issue?

This concept must be adapted to each nation’s own GDP, the level of development of its healthcare system, and its epidemiological data. In other words, in the USA, the question may be whether there are 2,000 or 3,000 DaVinci robots in operation, but this is obviously not the focus in Hungary. But let me give you an extreme example: there is a country in Africa where there is currently no pathologist working and no radiotherapeutic equipment in operation. Obviously, the focus there is not to install robots and MR devices, but to train the basic staff, develop the minimum diagnosis conditions, and create the conditions for tumour surgery. All I want to say is that these must be country-specific programmes, and in the ideal case, it would be good to allocate a suitable budget to the finalised concept.

What is the situation in Hungary in this regard?

In addition to the sad numbers, Hungary is also fortunately at the forefront in terms of being one of the first among European countries to have a National Cancer Control Programme. In addition, Hungary was the first to create a comprehensive cancer centre in the Central and Eastern European region—this is us, the National Institute of Oncology. I would like to note that it has now become an EU recommendation that comprehensive cancer centres should be established in all member states by 2025.

We have reached the European average in terms of the organisation of the profession, the development of patient pathways,

and as of today, I can say, that the same applies to the quality and the level of development of the clinical equipment applied here. All this has been achieved over the last ten years. However, at the moment, for all further developments that certain last step is missing: assigning labelled funding to the anti-cancer programme and being able to spend on it in an organised and planned manner.

Does the suspension of the EU funds affect the implementation of the plans?

Cancer research is definitely affected by the issue around the Erasmus and Horizon Europe programmes—hopefully only temporarily. What is even more painful is that

the suspension of RRF resources has a much more significant impact on research and delays the development of equipment and infrastructure.

It’s no secret that last April, together with the previous minister, we laid the foundation stone of the institute’s new one-stop-diagnostic block. At that time, it seemed that the construction could start in the autumn of 2022. So now this is also a postponed project, but we hope that it will be built, albeit with a delay.

What substantial quality improvement would this have brought?

The project would have included the demolition of our old building, and a four-storey edifice with a two-storey underground garage and a large, 11,000-square-metre, one-stop-diagnostic block would have been built in its place. Among other things, PET-CT, PET-MR, and our invasive endoscopic diagnostics would have operated there, and the department of pathology would have moved there as well. At the top, on the fourth floor, there would have been a so-called national telemedicine centre, through which we would have been able to connect the entire country through so-called virtual onco teams.

What does that mean?

Basically, this would mean that patient does not need to bring his CT or MR images to the examination on CD or collect his histology from the department of pathology. Instead, these documents are scanned and electronically transmitted, stored, and connected to the nineteen county and ten Budapest oncology centres. In this way, virtual onco team meetings could be held without physically moving the patient. This would have been a HUF 31 billion project. It is also currently being postponed, apparently along with other health programmes. It is well known that the renovation of several hospitals has already been put off because of this, for instance the further development of the Szent János Hospital.

What we hope is that what has been postponed will not be scrapped completely,

and we will eventually receive the funds for these programmes. The bigger problem is that these projects should be completed by 2026. In practice, this means that some programmes will be postponed to the next budget cycle due to lack of time. We regret this and we are expecting a political solution to be found in Brussels as soon as possible.

What results can the National Institute of Oncology show in the field of cancer research?

In oncology, one of the preconditions of a comprehensive cancer centre is that fundamental research, clinical research, and the translational research connecting these all operate at a high level. We have six research departments that specifically deal with this. In recent times, this performance allowed us to achieve a good rating even at the international level. We have been included in the top 50 research institutes in Hungary (the ranking is established by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office). Furthermore, the Institute was awarded the title of excellent research centre by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. So, we have significant results in these areas, the metrics of which are the number and value of high-quality international publications with a high impact factor.

Where do you see potential for growth?

It is a hard task not only for a national institute, but even for a university. If there is a breakthrough and we discover certain things—come up with new research results—thanks to which a medicinal molecule is created in our research departments, it is only the tip of the iceberg. From there, one should get a patent and move on to testing and finally to production. All of this is impossible without the appropriate amount of capital behind it, based on which the actual drug development can start. However, you should know that our university and oncology institute researchers are not businessmen. There are many steps between a breakthrough in fundamental research and its practical use in healing. This also requires business steps, in which a Hungarian fundamental researcher is typically not skilled.

Does the Institute get help with this?

Yes, we are working to bridge the gaps that, unfortunately, can also be identified not only in Hungary but in several Eastern European countries. The goal is not only to have good fundamental research capacities, but also to make them useful. Obviously,

at the government level, this would mean that at the end of the process, not only social, but also economic benefits are realised.

In this regard, there have been several consultations with the National Research, Development and Innovation Office as well as with the Ministry of Innovation and Technology in recent months.

What state-of-the-art solutions is the Institute currently working with?

Artificial intelligence is considered a very exciting field in oncology, whether it comes to imaging or pathological diagnostics. The software must be taught to recognise certain changes; if this happens, a lot of labour can be saved. This is particularly important for screening examinations. In the case of these, thousands of images of thousands of patients must be scanned. It should be known, however, that the vast majority of screening examinations—thank God—end with a negative result. If these tests are automated, pre-screening could be performed through the automation, and only in the case of the few dozen patients where this is necessary should a doctor be involved. With this, we could not only save human resources, but also increase efficiency. In addition, we now use robotics in several places.

Can you tell me more about this?

Although a few years behind some other countries, Hungary also got to the point where, with the help of an EU consortium project, we installed two Da Vinci surgical robots here at the Institute and the Jahn Ferenc Hospital at the beginning of 2022. By putting them into operation, we were able to successfully launch robotic surgery techniques in tumour surgery. In the first year, we were able to perform 463 operations, and the scope of the programme is currently being expanded—Semmelweis University and the University of Pécs have also joined in. Thus, there are already four surgical robots operating in the country, and as far as I know, the procurement of robots is also in progress at the clinics of Debrecen and Szeged. We are also waiting for the second robot in our thoracic surgery centre, which would complete our oncology robotic surgery profile. If everything goes well and funding is found together with NEAK and the Interior Ministry,

we will be able to serve patients with seven robots by the end of the year.

How does robotic surgery work?

It is important to note that although we have come a long way, a robot still does not operate. If we look at the history of tumour surgery, we can say that in the beginning, surgeons only performed so-called open surgeries: when the chest and abdomen were cut open with a long incision, the tumour was removed, and then the surgical area was stitched up. This process is typically followed by a long recovery period. The next step was the era of the minimally invasive, so-called laparoscopic techniques. These are also known to the public as ‘keyhole surgery’. During such an operation, the surgeon uses small tubes and trocars to make small holes next to the navel in places that heal well. After that, the operation continues with fibre optic devices, followed on a TV screen, but with manual manipulation. These trocars and the cutting and suturing devices inside are controlled directly by the surgeon.

Compared to this, is robotics a breakthrough?

Yes. It is a NASA development, perhaps developed during the Gulf War several decades ago. The concept came from the idea that it is too risky to take the best surgeons to the front line and operate on soldiers injured in action. It was realised that these minimally invasive surgeries can also be performed remotely with robotic arms. What happens here is that fibre optics and manipulation tools are attached with small trocars onto robotic arms—in that sense, it is similar to the laparoscopic technique. However, these are not moved by the surgeon standing directly next to the patient, but instead, robotic arms are attached to them. And the surgeon can sit in front of a console in another room, but without washing up, where he can manipulate these robotic arms with his two legs and two hands. The surgeon sees a three-dimensional image in front of a console capable of 10–14x magnification. It’s like being inside the patient while moving the robotic arms.

Is this technology expensive?

This is not a cheap sport. But if we use such a robot optimally—i.e. we perform at least 400 operations with it a year—then the specific costs are reduced, and it can even become a cost-effective procedure, although the primary goal is not this. Robotic technology also brings additional functional results from the patient’s point of view. For example, a patient with prostate cancer can return to work sooner, which can even be seen as a net economic benefit. His quality of life may also improve: his catheter can be removed sooner; he will be continent sooner and perhaps his masculinity will also return sooner and to a greater extent.

Are there more advantages of the robotic technology used in the field of surgery?

The robotic arm can filter out hand tremors, and due to the higher magnification, it is possible to operate much more precisely. All movements are performed by the surgeon, only his intention is conveyed to the surgical area by a robotic arm. This means that the dissection is even more precise and delicate, the surgeon can operate with even less movement and tissue damage, sparing blood vessels and nerves. As a result, there will be fewer complications, and the recovery time will be faster—the patient can go home within 2 to 3 days even after a major operation.