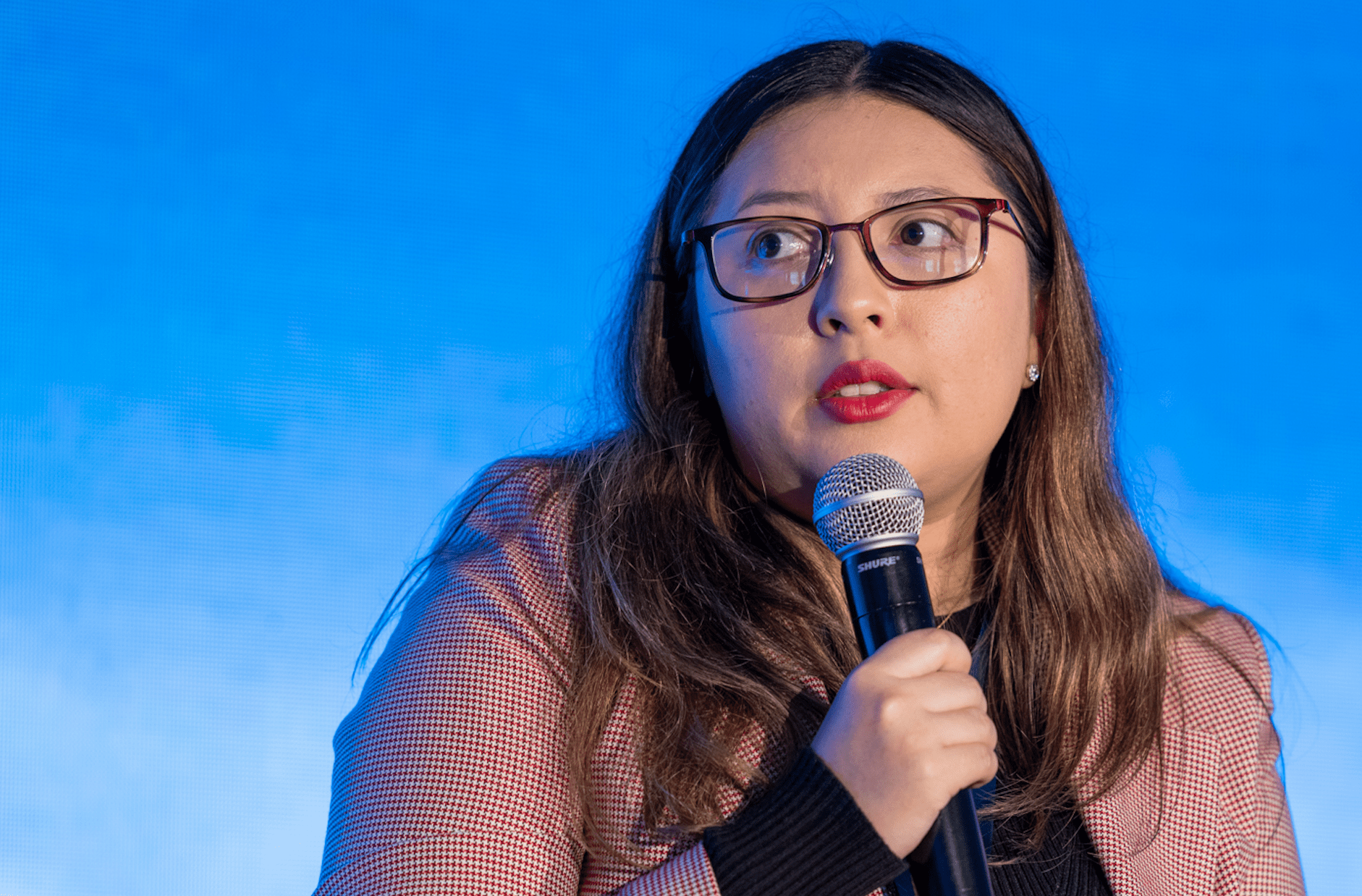

Amanda Raquel Martínez is an economist, economic risk analyst and specialist in public sector issues currently working at the United Nations World Food Programme. During the MCC Budapest Summit International Conference organised by Mathias Corvinus Collegium she gave and interview to Hungarian Conservative.

What does your job the UN World Food Programme entail?

I am an economic risk analyst. Which means that I scan, monitor, and assess the potential economic drivers of any increase or decrease in food security. This means that I scan economic indicators, developing economic news, and any other event that is going to affect food security at all times. I also study and analyse the interlinkages between conflicts and climate change and natural hazards and economics. Meaning that conflicts can also deteriorate economic prospects and increase economic risks, but also climate change—economics is a reinforced dimension of conflict and climatic crises. It sounds like a lot, but it is a really interesting job.

Did the war affect your job? And if so, in what way? Is there more pressure, do you have to do more?

Yes, for sure. The conflict in Ukraine did increase our workload. Because now we’ve seen the negative spillover on many countries and regions around the globe. And now we are demanded to do more tailored analysis—about how this conflict, how these developments are going to affect the economy and the risk of food security of a given region, especially those who have a fragile contact with the conflict, but also those with the long standing underlying economic vulnerabilities. For example, we’ve seen so many countries that have higher, double or even triple digit inflation, and these numbers are rising. So, for us it means covering more material, and providing more tailored analyses to these countries.

Do you have any insight on how the looming food crisis could affect Hungary? Is there a chance that it will reach us?

Unfortunately, I do not cover Hungarian issues or European nations, I basically cover western and southern Africa and Latin America. However, we’ve seen that a food crisis is looming, and it has worsened since the Covid-19 pandemic, with the price increases. We can also see that the caseload of people in humanitarian fields increased. Five years ago, the number of people at risk of starvation was at 80 million, and with the Covid-19 pandemic the number increased to more than 200 million, and now we are talking about 345 million. That’s a lot.

And as we don’t see any resolution of the conflict, it seems that it is going to be a protracted crisis.

And obviously it is going to have ramifications around the globe as it already did. We see high inflation, and the reaction of central bank authorities tightening monetary policies and raising the interest rates. That obviously is going to have an impact in terms of economic growth, in terms of investment opportunities, because it will increase the borrowing costs for many, and in particular, it is going to wipe out small businesses. So, it is going to increase the economic vulnerability of many, especially for the lower- and middle-income classes, because they are less protected and less equipped to secure their assets, and because they allocate more of their income to basic expenditures such as food, energy, sanitation and so on and so forth. So, we see that prices are rising and in 2023, energy prices are still going to be high. What is especially worrisome is having a passthrough in fertiliser prices, because fertiliser prices are really relevant for crop-production. And for many parts of the world, who are highly dependent on Russian and Ukrainian fertilizer production, so its going to be really impactful. And on top of that, we’ve seen the debt crisis looming meaning that right now we have at least a quarter of a million dollars that are going to be due in late 2022. Many countries are at a risk of a default and obviously this is going to have an impact in terms of economic deterioration and in terms of social indicators, especially in terms of poverty. And we’ve seen the number of people under poverty rising. And this is very concerning. But the overall take is that we’ve seen a regression of developing outcomes to the levels of 20 years ago. It’s a really concerning and dire situation. So, the food crisis isn’t here, but we are fast approaching that.

Not only energy, but also grocery prices are rapidly increasing. Is this an indicator of food shortages coming, as there is less of the products that we are trying to buy, or are they increasing because the energy prices are also driving up transportation costs?

I would say that the main cause of the prices increasing is not a huge food shortage globally, I will say that the prices are going up because of the energy import prices rising, and in Europe the main component of inflation is energy prices. It is the high energy dependence on Russian gas and fuels that is driving up this inflation. You’ve seen that now it is more costly to import the energy, but also to use the energy through the whole production chain. So, that is affecting all the sectors: transportation, food production, and so on.

Historically, wars have been accompanied by food shortages. But has there ever been a case where a conflict affected the global economy or the food situation as harshly as it has now?

I believe that what we are seeing now is unprecedented, because of the relevance of these two key countries. Not just in terms of food, but also in terms of oil and fertiliser and energy production. So, it’s a very complex crisis that is affecting many essential commodities. I don’t have any recollection of something of the nature, but it is also an effect of lingering shocks, because we are just coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic, which means that countries were less equipped and less prepared to deal with this new shock. So,

I don’t think that something like this has ever happened before.

At least globally speaking, not regarding particular countries. And adding to the shocks we now also have to deal with climatic shocks, that of course affect any and all agriculturally dependent nations. So, it’s a complex dynamic that is mutually reinforced by conflict risks, economic risks, and by the risk that the conflict is becoming protracted. So, the way I see it, in a couple of years’ time we are still going to have high energy prices, high food prices and less fiscal capacity from the governments to offer protection or to cover the price of the import of essential foods. And on top of that, there is also a debt crisis as I already mentioned.