‘Clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as gold and silver.’ Xi Jinping’s oft-cited dictum vividly captures the ideological foundation of China’s environmental discourse, framing ecological preservation not as a constraint on development but as an integral element of national prosperity.

On the broader global landscape, the three major powers approach the green transition in markedly different ways. China relies on central planning and technological innovation, the European Union employs regulatory measures and sanctions, and the United States pursues climate protection through incentives and subsidies.

Although China is often criticized for playing a limited role in international climate affairs and for not taking on responsibilities commensurate with its emissions and economic size, over the past decade and a half, it has introduced numerous measures to reduce emissions and combat climate change—guided primarily by its own domestic political and economic interests.

The Priorities of Chinese Climate Policy

China is regularly criticized internationally for not taking an active role in global climate-protection initiatives, even though the scale of its greenhouse-gas emissions and the size of its economy would warrant greater involvement. While such criticism is partly valid, China’s role and contribution merit closer analysis, particularly because the country’s position is subject to ambiguity: while it is still classified as a developing state, it is also the world’s second-largest economy—and the second-largest emitter of carbon dioxide.

China’s climate-protection efforts are shaped above all by domestic priorities: promoting economic growth, winning the technological race, and strengthening the regulatory framework to support these goals. This approach stands in sharp contrast to that of Western countries, which typically strive to fulfil national goals and international commitments concurrently.

‘China’s climate-protection efforts are shaped above all by domestic priorities’

Taking these factors into account is essential to understand the extent to which China contributes to global climate efforts or prioritizes its own interests. The first significant criticism directed at the country was related to the Kyoto Protocol, as China, being classified as a developing nation, was not obliged to commit to concrete emission-reduction targets, even though its rapid economic growth was a major driver of rising global emissions.

China and the Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol was adopted on 11 December 1997, but due to ratification difficulties, it entered into force in 2005. Its importance lies in the fact that it was the first global climate agreement to set legally binding targets for the reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions. As part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the protocol adopted the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’, imposing biding obligations only on developed countries.

The first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, covering 2008 to 2012, required developed countries to reduce their emissions by an average of 5 per cent compared to 1990 levels. However, the targets set for individual countries varied, taking into account their economic situation and historical emission levels. The European Union, for example, committed to an 8 per cent reduction, the United States—which ultimately did not ratify the protocol—to 7 per cent, and Japan to 6 per cent. Some countries, such as Russia, only committed to maintaining their 1990 levels, whereas Australia was allowed to increase its emissions by up to 8 per cent.

To help achieve these objectives, the protocol introduced an innovative flexibility mechanisms. Through the emissions trading system, for example, countries could trade emission allowances, making the reduction process more efficient. China excelled in this mechanism, with 880 registered projects achieving record numbers of certified emission reductions and offsetting up to 590 million tons of carbon dioxide annually.

However, there were also serious concerns. The world’s two largest emitters reached a deadlock over the protocol, as the United States refused to ratify it citing China’s exemption, while Beijing justified its passivity by pointing to Washington’s rejection. The rigid divide between developed and developing states soon proved unsustainable, highlighting the need for a more inclusive framework. The solution was found in the 2015 Paris Agreement, which obliges all countries to contribute through nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Meanwhile, China took notable domestic steps consistent with the Kyoto framework. Its 2005 Renewable Energy Law set national targets and introduced feed-in tariffs, while the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010) established binding energy-efficiency goals, reducing energy intensity by 20 per cent. In 2006, China released its first National Climate Change Assessment Report, recognizing the severe risks of climate change, and soon after engaged more actively with the IPCC. Mounting domestic air pollution, the so-called ‘airpocalypse’, also pushed authorities to address coal dependence (at the time, 66 per cent of the country’s power generation relied on coal).

‘China pledged to peak emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060’

These measures prepared China for the paradigm shift of the Paris Agreement, which replaced top-down targets with the aforementioned NDCs. This framework suited Beijing’s strategy, as it aligned international commitments with its domestic priorities. China pledged to peak emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, reflecting both global engagement and the pursuit of national economic and technological interests.

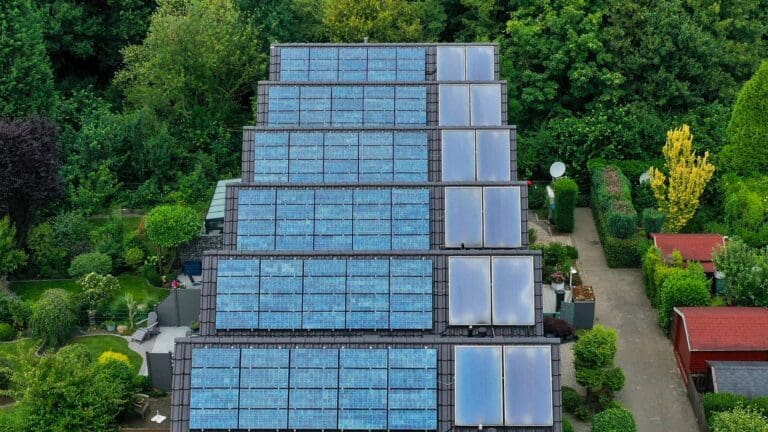

An illustrative example came in 2024, when the export of Chinese solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles made a substantial contribution to global emission reductions. While Chinese production generated about 110 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, the use of these products offset roughly 220 million metric tons annually. Over their life cycle, they are expected to help avoid nearly 4 billion metric tons—40 times their manufacturing footprint. Including overseas production and clean energy projects, the annual avoided emissions reached approximately 350 million metric tons, comparable to Australia’s total emissions in one year. These figures highlight both the tangible impact of Chinese technologies on decarbonization and the consolidation of China’s industrial dominance in the green economy.

The criticism the country faced during the Kyoto era notwithstanding, today’s global green transition hinges considerably on the Asian giant’s strategic choices and progress toward greening.

Related articles: