Tímea grew up in Körösfő, Transylvania (Izvoru Crișului, Romania), immersed in a rich Hungarian folk culture. After attending a teacher training college in Nagyvárad (Oradea), she studied psychology at the university in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), and later pursued financial studies in Los Angeles. Her family, community, and teachers gave her guidance and values that she continues to build upon to this day. She has founded and leads two diaspora organizations, including North America’s only Hungarian-language theater.

***

‘My childhood experiences define my work today, ’ you said. Could you elaborate?

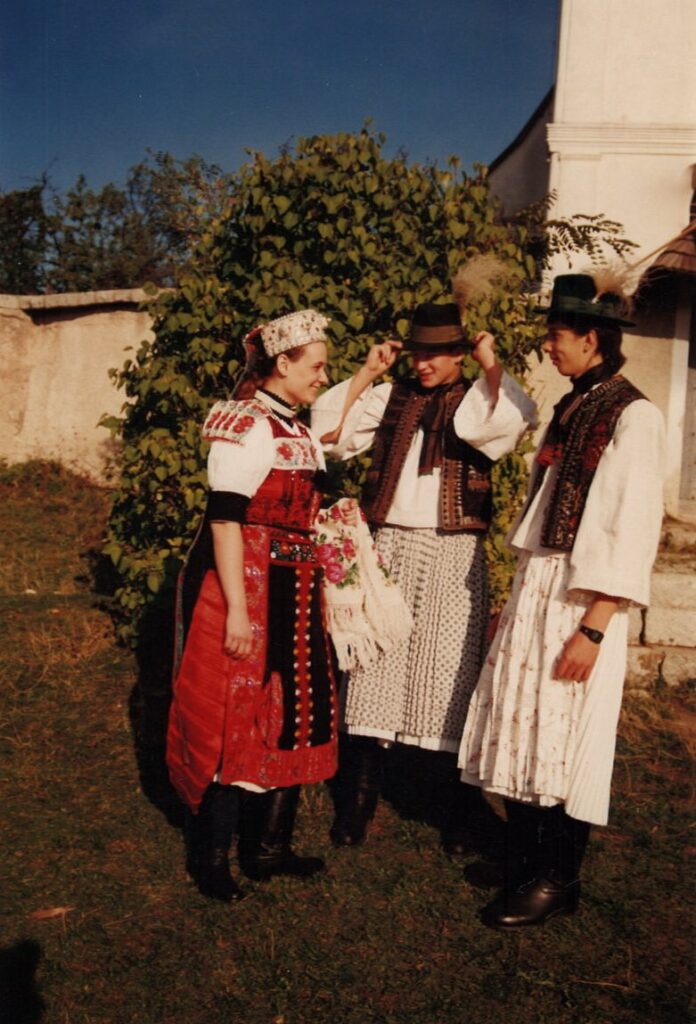

I was born and raised during communism in Körösfő, in the Kalotaszeg region, at a time when talking about Hungarian identity wasn’t really allowed. Still, we were raised to be proud of our culture and to carry it forward. The local folk culture there is very rich: the folk costumes are beautiful, the embroidery and wood carvings are exquisite. My father was a very talented man; whenever I asked him to draw something for a special occasion, he always gave me something far beyond what I imagined. I still have those drawings, and they remind me of a message: ‘Give more than what is expected of you.’ That’s one of the most important things I took from him: whatever I start, I should do it with more than 100 per cent dedication. I believe that what makes something truly special—consciously or not—is the tiny details we put in. I’ve found that people appreciate it—it’s what creates lasting memories. That’s especially important because you never know who you’re going to touch, or how. In California, there are more and more third-generation Hungarians having countless things to focus on—it’s up to us to show them why their Hungarian roots matter, it’s our job to plant and nurture those seeds. We might not know when they’ll grow—maybe in ten years—but the result will come. The energy invested in me by my parents, grandparents, my teachers and the entire community—because back then it was considered that an entire village is needed to raise a child—along with what I later received in Nagyvárad (Oradea), cannot stop with me, it needs to keep flowing, I have to pass it on. That’s my greatest motivation.

Tell us about those defining years in Nagyvárad.

At 14, I entered the teacher training college in Nagyvárad. Under the communist regime, there were limited opportunities to pursue further education or personal development. My Hungarian language teacher, Mária Tonk, advised me not to follow the crowd to the high school in Bánffyhunyad (Huedin), but to think about what I really wanted. I chose the teacher training college, and from that point on, she and everyone else supported me with special preparation classes…My father also advised me to ignore everything else and just focus on studying. He even accompanied me to the entrance exams in Nagyvárad. But since the exams coincided with my graduation ceremony in Kőrösfő, and he wanted me, being the top student, to receive my award in person, we returned home that morning. We missed the graduation, but I was able to attend the award ceremony, and then we went back to Nagyvárad. My father, who worked for the railway, tried to close an open door on the train, but as it rounded a bend, he fell out and died. My last memory of him flying through the air is with me every day and motivates me in everything I do. I studied hard at the college because I felt my father had paid a very high price for me to be there…

Back then, only two Hungarian teacher training colleges operated in Romania, and it was extremely difficult to get accepted into either of them, which provided a very high standard of education. We lived in the dormitory, and while the teachers tried to cram as much knowledge into us as possible, they also paid close attention to us outside of school—trying to substitute our parents in some ways. Teachers were very careful with me, not only because of my father’s death, but also because I was a very shy, timid child…

How did this shy girl become a stage performer, a director, and even a president?

As I grew up, my shyness started to fade, though I still remained reserved. Even now, when there’s someone who replies quickly, it may happen that I can’t join in the conversation because I don’t like to jump into other people’s words. Still, it’s true that the process of pushing my boundaries—initially unconsciously— began when I was preparing for the entrance exams. My comfort zone has gradually expanded since then. Living independently has increasingly forced me to face new situations and challenges. I was 14 when I left home, and at first the college was very difficult: we learned everything in Romanian, and I didn’t speak the language well since I came from a fully Hungarian-speaking region. After the 1989 revolution, the situation changed; everything became simpler. I could hardly believe I no longer had to study and stress day and night. But even then, I kept studying hard. The college prepared us thoroughly for our profession. Still, when we were assigned teaching posts, everyone was sent to combined-grade classes in rural villages—I, for example, to Kalotaszeg—while teaching posts in cities could be obtained only through competitive exams. Thus, in the fall, I tried my luck in Kolozsvár—and came in first, being able to choose between the two open positions. It was a huge performance at the time, and for me, it was a confirmation that hard work pays off. The school inspector had called my college teacher, Jenő Pál, to congratulate him on his student who had written a beautiful exam essay. Jenő Pál was a Szekler man, one of my role models, who regularly gave us moral education in his special Szekler style.

What happened afterwards? Why and how did you end up in America?

While I was teaching in Kolozsvár, I enrolled at Babeș-Bolyai University to study special education and psychology. But at the same time, teaching positions were being eliminated, there were fewer and fewer Hungarian children, and the Romanian economic situation kept getting worse. I increasingly felt that I should continue studying abroad. I wanted to get a PhD in psychology, become fluent in English, and do the kind of work I had started at an even higher level. I told my friends about my plan, and one of them suggested a U.S. summer cultural exchange program that would be perfect for me. Everything happened incredibly fast; within six months, I was already in America. Since then, I know: if you really want something and pursue it, it will happen. You don’t need to know in advance how you would get from point A to point B—it’s enough to know you want to get to B, and God will take care of it.

‘I studied hard at the college because I felt my father had paid a very high price for me to be there’

That summer, I ended up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, working at a ten-week youth summer camp. Afterward, I traveled with friends I met at camp to Wisconsin, where we worked for a month, then I spent two weeks traveling on the East Coast. Then I went home and continued my university studies. When the Romanian Head of Department saw me, he asked: ‘Why did you come back? Why didn’t you find yourself a John and stay over there?’ I thought he was joking. After all, I had gotten into the university through a very difficult entrance exam—of course, I wasn’t going to just walk away and give up the spot I had taken from someone else…The same happened the following year. When I requested another letter of recommendation, the school inspector said: ‘I’ll give you one more, but if you come back again, I won’t write you another.’

I was convinced that he was joking this time too, but gradually the thought began to grow in me that maybe he really doesn’t care whether those who started university actually finish their studies and become useful members of society…Over time, this thought became an increasing disappointment for me. I felt like they didn’t really have any particular plan for us—it didn’t matter whether I stayed or left…When I talked about this ten years later to someone from Transylvania, she replied: ‘Of course they wanted you to stay abroad—one less good Hungarian at home!’ I didn’t even think about that at the time.

So, you returned home a second time, too?

Yes, I finished university, passed my language exams, and tried to figure out what to do next. In the early 90s, the Romanian economic situation was quite unstable—there was massive inflation, and I was constantly relying on financial support from my mother, who lived in Hungary and ran her own business. Sometimes I had to ask my uncle, who had owned one of the best restaurants in the area back then, the famous Kurucz Inn, to give me food, or knock on the neighbor’s door for dinner…Meanwhile, during the summers, I experienced in America that life is predictable there: if someone was willing to work, they could be independent and achieve anything they wanted. That’s what ultimately led me to the conclusion that I should return to the U.S. and get my PhD there.

In 2000, I came back to Southern California with the intention to stay. I found a sponsor who hired me and sponsored my green card. Since my home degree wasn’t fully recognized and I had always felt a big gap in my financial knowledge, I enrolled in a personal finance course. The program seemed so interesting that by the end, I could actually see myself as a financial advisor. I finished studying economics and accounting at UCLA in 2008. In the meantime, I interned at Merrill Lynch, but just then the American economy collapsed, and I was advised not to pursue investment banking as planned, but to focus on accounting instead. It took a year, a lot of studying, and hours-long exams to earn the so-called CPA license. After working for several firms, I started my own company. Since then, I’ve been working for myself, with a flexible schedule, which allows me to devote so much time to Hungarian causes. During tax season, I work very hard, but in the month before a theatrical production, I barely have time for my paid work. If I worked for someone else, they wouldn’t tolerate that.

When and how did you get involved with the local Hungarian community?

In the first years, I simply had no time for the Hungarian community at all—I was working and studying, with no free time at all. But my Hungarian identity always interested me, and after a while, I started missing it, like water or the smell of pine trees. As Maslow’s hierarchy of needs also shows, when a person tries to find their place in a new world, they focus on material needs and security rather than self-actualization or their cultural identity. When my financial situation started to stabilize, I sought out Hungarian communities and began attending their events. Soon, I was recruited to perform at a 15 March commemoration at the Hungarian House, and after that, they invited me as a performer to every event. Then they asked me to organize the programs as well. Meanwhile, I was cast in a theater play—I played Terka in Hyppolit, the Butler. I drive a lot as I live at least an hour from the Hungarian House in Los Angeles, so I recorded my role and also my partners’ role, and then listened to it while driving, and if someone got stuck, I could help them out. Meanwhile, Éva Szörényi, the ‘grand lady’ of the 56 events, passed away. After that, the old scouts gathered to discuss what to do next, and Uncle Sanyi Szoboszlai recommended me, saying I had such a good memory. Since then, every year I recite at the 56th monument. They saw that if I committed to something, I did it conscientiously, and they liked the result. I think it really matters that if you entrust someone with a task, you are sure it will be done well. This is a huge help in community life, especially when everything works on a volunteer basis. That’s why they invited me back and gave me bigger and bigger responsibilities.

Even establishing and leading an entire theater? How did that happen?

Los Angeles used to have a vibrant Hungarian theater scene with significant actors like Éva Szörényi, a Kossuth Prize winner, or Zita Szeleczky. Back then, 500–600 people attended each performance, but the numbers gradually declined, as everywhere in America. In the last performance of the Thália Studio, Hyppolit, the audience was around 300. Balázs Bokor, the Hungarian Consul General back then, organized a conference about the future of Hungarian community life on the West Coast. I was invited to give a presentation as a representative of the youth. I spoke about how important it is for the younger generation to take over the baton from the older one, as it happened with the Kárpátok Folk Dance Ensemble: when the leaders moved back to Hungary, Lívia Schachinger, the current leader, Csaba Varsányi’s sister, took over. The director of the Thália Studio, Enikő Óss, also moved back to Hungary and liquidated the theater, while those of us who had acted in the last show wanted to continue playing. During the conference break, several people approached me—including the Consul General and the editor in chief of the newspaper Magyar Napló—saying that I should reorganize the theater. Since I was already quite experienced as an accountant in nonprofit organizations, I gladly accepted the task of registering and managing the new theater. When we raised concerns about finances, Sandor Szoboszlai simply said: ‘Don’t worry about it, just do it, I’ll help.’ That’s how in 2011, I became one of the founders of the current theater, which bears Uncle Sanyi’s name as a sign of our recognition of him.

What made the current Hungarian theater popular and successful (again)?

Earlier, they generally performed comedies or non-musical stage productions. We sensed that people were craving bigger musical productions, so for our first performance, we chose Mágnás Miska and rented a 330-seat theater, which ended up completely full. In addition to the original cast of the operetta, we involved the Hungarian scouts and folk dancers. My goal has always been to engage as many people as possible because then they feel the performance belongs to them, too. They invite their relatives, friends, and acquaintances, thus filling the theatre and making more people part of the Hungarian culture. Anyone who has taken part in our performance wants to take part in the next one as well. I never say no to anyone, I thank everyone who volunteers, and I always try to find them a role. If nothing else, I give them a Hungarian flag to be able to express their love for their homeland. Some have traditional Hungarian costumes at home and are happy to bring them in to take part in the performance, to feel part of a team. That’s why we have so many people on stage, and that’s why our events are so successful. We had two performances of Marica grófnő (Countess Marica); we even dared to take on Csárdáskirálynő (The Csárdás Queen), which was actually my first big stage directing project.

Many doubted whether we could technically pull it off. Around the 100th anniversary of Csárdáskirálynő’s premiere in Budapest, it was celebrated everywhere. I watched the gala events and thought: why couldn’t we put it together, too? After I returned to California, I suggested to the others that we should do it. By then, our team was large enough that two people could sing the roles of Szilvia and Stasi, so I came up with the idea of a double casting within the same show: one singer would appear in one scene, the other in the next. At first, many looked at me puzzled, but I wasn’t afraid that the viewers wouldn’t understand because they knew the play and characters well. My intuition was proven right; that production was a huge success, and the performers were grateful. This was a complete innovation, after which I wondered: how can we top this?

I spent nearly a year thinking about what our next performance should be. I discovered Imre Kálmán’s Chicagói hercegnő (The Duchess of Chicago), which deals with a very relevant topic for the diaspora, since it’s about the meeting of American and Hungarian cultures, and its lesson is to be tolerant of different cultures but to be proud of ours—I found it ideal. It was also a great success. There were about 50 people on stage, and our group photo shows how happy everyone was and what a great experience it was for them. Not to mention, the 330-seat theater was expanded with extra chairs. All in all, our theater events draw in 400–450 people, which is a huge achievement here in Southern California.

Have you ever had any financial or personal problems?

For roles that local artists cannot undertake, we invite guest performers from Hungary. Plane tickets, local transportation, accommodation, and food aren’t terribly expensive. We don’t pay much for performances. The artists we invite are deeply committed to Hungarian culture; they know we work on a voluntary basis with a low budget, and they support our efforts with genuine humility. Zsolt Dánielfy, recipient of the Jászai Mari Award, for example, regularly helps us with directing and scriptwriting. He is a close friend and mentor to all of us. His high standards and impressive professional expertise serve as an example for our entire team. Our main sources of income are ticket sales, donations from community members, and funds obtained through grant applications.

‘When the path is like a shell, if we put in the work, the result will be a pearl’

Regarding personal challenges, I’ve lived through difficulties that I firmly believe God gave me so that later I could create things that might have seemed impossible. And I also had great teachers. For example, during one hypnosis class, Professor Jenő László Varga—a very famous psychologist—held up a pencil and asked: ‘Who believes that they can’t break the pencil with one finger?’ No one dared to raise their hand except me. He started asking me: ‘What do you think it takes to break the pencil?’ I listed strength, speed, etc. Finally, he allowed me to press my finger on the pencil, and it broke. Everyone started applauding. After picking up the pencil from the floor, the professor told me: ‘If you ever encounter situations in life that you think you can’t solve, remember this pencil.’ I still have it, and I still draw energy from it, if I need to. In fact, having learned from this example, I try to encourage and inspire others as well. Because we are indeed all capable of more than we know or believe about ourselves. Let us be grateful for all the friends and mentors who genuinely care about us, and let us not forget: even when we face challenges, when the path is like a shell, if we put in the work, the result will be a pearl…

What’s your most recent and newest ‘pearl’?

Our main goal is to provoke thought as well as to entertain, so lately I try to produce performances that serve both purposes. Our most recent performance, Hymn to Peace, was presented on the Day of Hungarian Culture, expressing our solidarity with our fellow Hungarians in Transcarpathia (Ukraine). The first part included ‘pearls’ of Hungarian culture, this time focusing on contemporary art with musicalized poems in which Kinga Újhelyi, a Jászai Mari Award-winning actress from Debrecen, Hungary, was a great help to me. The second part consisted of comedies, chansons, and cabaret songs, which took our audiences, who deeply love nostalgia, to the world of Budapest in the 1920s and 30s.

Our next show, on 4 October, will be completely unique compared to all previous ones, as I’ve invited a full production from Hungary. Bor, mámor, szerelem (Taste of Love) is a comedy packed with operettas, featuring actors from the Petőfi Theater in Veszprém, the Vörösmarty Theater in Székesfehérvár, and even the Operetta Theater in Budapest, put together by Eszter Sára Váradi from Székesfehérvár. It’s so well-rounded that it cannot be taken apart; I cannot incorporate local performers into it, but before that, we will have a one-hour performance presenting the historical Hungarian flags by local actors, dancers, and musicians. The beautiful embroidered flags are ready and haven’t yet been introduced to the local community here. My goal is to present them not only on 4 October but also at other local events and in other states as well. The flag is part of our Hungarian identity, and by getting to know better how it changed over time, we can also experience what we, Hungarians, are made of. I founded the Southern California Hungarian Heritage Foundation in 2021 to be able to create such productions for a deeper understanding of our roots.

Please also elaborate on the foundation.

For many years, we’ve been holding commemorations of the Trianon Treaty of 1920 at the Hungarian House on the occasion of the Day of National Unity. We started with poems and related songs, but I always tried to give something new. Thus, in 2019, the programs ‘Hungarian Calvary’, in 2020, ‘Blessed be my nation, blessed be the Hungarian nation!’, and in 2021, ‘On this side of the Tisza, beyond the seas—my soul, my feelings have inherited…’ were created as memorial performances. With the help of our website, we also try to present in depth the themes raised in these memorial performances to the local community and the Hungarian diaspora worldwide.

The ‘Hungarian Calvary’ program, for example, was inspired by my visit to the Trianon memorial of the same name in Sátoraljaújhely, Hungary, an experience which I wanted to share with others. Thus, the introduction of the memorial and, through it, the exploration of the notable features of the cities in the detached territories formed the basis of the commemoration. The show was followed by so much interest that, upon request, we also made a DVD version, which we present at various workshops, incorporating the personal knowledge of the participants. A continuation of this project on our website is the presentation of Hungarian heritage in the Carpathian Basin under the title ‘Detached Territories’, where approximately 100 settlements and national values have already been showcased so far. Some help would be very welcome to continue this work…

Besides this, we organize literary evenings at the Hungarian House and other venues and participate in national holiday commemorations. Furthermore, we take part in the ‘Bread of Hungarians’ program, which we tried to popularize by distributing flour in small satchels, spreading the significance and message of the 15 million grains of wheat to as many Hungarian communities as possible in the western region of North America. Finally, I’d mention the presentation of the Erdélyi Helikon, which, as a Transylvanian, has become a heartfelt cause for me. Together with Zsolt Demeter, of Transylvanian origin and leader of the Hungarian Reformed Church in Phoenix, Arizona, we organized and presented a memorial program honoring the Helikon writers, collaborating with Éva Medgyessy, a literary historian from Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș, Romania).

Finally, a few words about the Hungarian House, where it all began…

This is a cultural center, where I’ve been the cultural director since 2010. At the events I organize, all three mentioned organizations participate at some level. At the national commemorations, the Kárpátok Hungarian Folk Ensemble is one of the organizers as well. We try to cooperate with everyone as much as possible.

‘No matter how clichéd it sounds, love really can work miracles’

Several Reformed churches operate here: the ones in Ontario, Hawthorne, Hollywood, and the San Fernando Valley—we try to work with them too. For example, we always invite a pastor to say a prayer at national holiday commemorations. We brought several literary events or thematic exhibitions, such as the one linked to a fundraising for Transcarpathia, to the reformed communities in Ontario, Hawthorne, or even Las Vegas. It took a united effort to help the victims of the fires in the Los Angeles area in January this year, when donations were received from Hungarian churches and organizations in San Francisco, San Diego, Phoenix, and even the East Coast. One of the three Hungarian scout troops is related to the Hollywood Reformed Church, the other two hold their meetings at the Saint Stephen Catholic Church; they usually participate in our national celebrations. The leaders of the American Hungarian Baptist Church regularly attend our events.

The current Consul General, István Gróf, is a fantastic person who does a lot to enable the various organizations in the local Hungarian community to work together successfully. We can only do great things if we work together and help each other rather than compete. Miklós Pereházy, the president of the Hungarian House, is a firm and decisive man who is not afraid to face potential conflicts, but his decisions are always guided by the interests of the local Hungarian community. I respect him because he is an exceptionally educated and well-read person, and I’ve witnessed multiple times how he stands up for those who are attacked or find themselves in a disadvantaged position—due to financial, personal, or emotional reasons. I wouldn’t say we agree on everything, but we discuss everything openly. People can feel when you treat them with love, and then anything can happen. We use the word ‘love’ a lot, but when you truly approach someone with love, there are no obstacles; anything can come to fruition. No matter how clichéd it sounds, love really can work miracles.

Read more Diaspora interviews: