Panni Ludányi (née Nádas)’s parents fled Hungary during World War II. She was born in an Austrian refugee camp. The family settled in Cleveland, OH, where they became prominent members of the local Hungarian community. Later, she moved to Ada, OH, with her husband, András Ludányi, because of his academic work; thus, they no longer lived in a Hungarian-populated area. Nevertheless, they made efforts to raise their children speaking Hungarian and to remain active in the Hungarian community—partly through the Hungarian Association and its annual Congress, founded by the Nádas family, and partly through the Hungarian Communion of Friends (Magyar Baráti Közösség, MBK) and its ITT-OTT conferences, established by András and his circle of friends. Although they eventually divorced in 1997, it was András who suggested to me that I should also interview Panni, pointing out that she had been just as active as he was, though more often from the background, supporting both him as well as the Hungarian cause in the U.S.

***

As your sister-in-law, Dr. Gabriella Nádasné Ormay (Kuni), has already shared with us, her husband and his siblings—including you—were all born in a refugee camp in Innsbruck, Austria. Could you briefly describe the circumstances? Do you have any personal memories of the camp?

Yes, all three of us were born in Austria: Gyuszi (Gyula) in 1945, myself in 1947, and Jancsi (János) in 1949. I was given the name Julianna after my grandmother, since we were born on the same day, but from the very first day, my father called me Panni, so within Hungarian circles, that is the only name I go by. We were granted permission to immigrate to the U.S. after five years in the camp in 1950. Our sponsor was a Hungarian Reformed congregation in Pennsylvania, which provided us with housing and meals for six months.

I don’t have many memories of the camp itself, since I was only three when we left it behind. My parents told me that during the long voyage across the Atlantic, I became ill, and for several days I was taken care of in a separate hospital ward, where I missed them very much. But apparently, I was well cared for and even received better meals during the more than two-week-long journey. They also told me that we lived in a single room in the camp, not under the best conditions, but still with everything we needed. A few years ago, I traveled back to Austria to find my birthplace—according to my papers, it was Zell an der Pram, a small town on the Pram River. At the refugee office, however, I was told that no physical trace of the camp remains there, so it wasn’t worth visiting. Later, when my aunt passed away and we cleared out her house, I found a small painting. On the back she had written: ‘This is the house where we lived’—this became my only tangible evidence that my birthplace had once existed…

During the six months spent in Phoenixville, PA, my father and my uncle began seeking contact with Hungarians living in the U.S., and came in touch with some from Cleveland, too. Uncle János had already been a great organizer back home; it was especially important to him to live in an area inhabited by Hungarians, so they all decided to move to Cleveland. We didn’t live on or near Buckeye Street, the historically Hungarian quarter, but on the west side, where many Hungarians also lived. We rented a small house, close to the house where Uncle János, Aunt Rózsa, and my grandmother, also Rózsa Nádas, lived together in a single household. In 1957, my parents bought a house in Lakewood, and soon János, Rózsa, and my grandmother moved there as well—they lived throughout their entire lives just a few houses apart from one another. My father passed away in 2007, at nearly 102, and my mother, 15 years younger, died in 2012. What is truly interesting about them is how their marriage and their escapes became intertwined…

Tell us then, where did they meet and how did they end up in Austria?

My father earned a doctorate in economics and was appointed to the Hungarian Foreign Trade Bank, where he held one of the highest positions. My mother had also completed two years of university, which was rare for women in the 1940s. She was also hired by the Foreign Trade Bank; that’s where they met. They got engaged and married on 28 November 1944, on my father’s birthday. When I took my parents out for lunch on his 95th birthday and their 56th wedding anniversary, I asked why they had gotten married on his birthday. He asked me back: ‘Have I never told you about that?!’ and finally shared the story.

My father’s birthday fell on a Monday, so my mother requested a day off in order to hold a party for him after work. However, on that very day, my father was told that all the documents of the Ministry of Finance were being loaded onto a train to be evacuated from Budapest ahead of the advancing Russian front, and the highest-ranking employees were obliged to board the train themselves at six o’clock the next morning to safeguard the shipment. So my father called my mother: ‘My dear Ibi, I don’t think you would come with me, since we aren’t married, so please marry me today. Your uncle is a judge at the Curia—perhaps he can arrange for the official papers to be ready today. We don’t even need to gather guests; when they arrive at the birthday party, they will at most be surprised that we are also celebrating a wedding.’

Since my father was allowed to take four family members with him, his siblings and my grandmother went along. A few weeks later, the train left the country and remained in Austria for six months. Then my father and his colleagues were told: the situation in Budapest had calmed down, they could safely bring the documents back, but each family could decide for themselves how to proceed. In the meantime, my father was warned by a very good friend—I don’t even know how, since in those days one couldn’t simply make a phone call—that higher-ranking bank officials could easily be arrested at the border and deported to Siberia. Therefore, in the end, they all decided not to return home.

Your father and his two siblings, who all earned PhDs in economics in Hungary, became prominent members of the Hungarian community in Cleveland. What childhood memories do you have from that period?

It may sound somewhat unbelievable, but although I never lived in Hungary, we always spoke Hungarian at home; I never spoke a single word of English with my parents. Grammar is close to mathematics; perhaps that’s why I can express myself so well in Hungarian. For example, Jancsi sometimes asks me how something should be said. In Cleveland, there was a self-education circle, and we attended its programs. I don’t know why, but we didn’t go to Hungarian weekend school, yet we were very active as Hungarian scouts. When we moved to Lakewood, there was no Hungarian community around us, but since it was not far from Cleveland, we continued participating in Hungarian community events. In addition, we did a lot of sports, again among Hungarians. We went swimming twice a week with a Hungarian coach. When he moved, because he was invited to lead the U.S. Olympic rowing team, we started fencing, also with a Hungarian coach. Later, when Jancsi went to Western Reserve University and Gyuszi to Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland, both of their coaches were Hungarians, too…The ‘break’ in our Hungarian life happened when I moved with my husband to Ada, since there was really no Hungarian presence at all.

Once I measured the distance between our house and the Catholic school, it was exactly one full mile. Because my mother did not want us to eat lunch at school, we walked this distance four times a day. Three streets away lived a girl who also attended Saint Rose Catholic Elementary School, and with whom we sometimes talked on the way. One day, she appeared at a Hungarian scout meeting, and I did not understand why she was there. Only then did I learn that she was Hungarian; during our walks, she had never spoken Hungarian—she said because she was an only child and was afraid that if she started speaking Hungarian with us, she would have to attend all sorts of Hungarian programs, such as scouting, and she had not yet decided if she wanted to…Márti eventually became my best friend; later, we attended the same Catholic high school as well. The Catholic elementary school, by the way, had a very good mathematics curriculum; I performed very well at a few competitions, so I continued studying math and eventually became a math teacher. When I completed fifth grade at the Catholic school, I took an intelligence test and I was moved up to seventh grade…All of my siblings skipped a grade as well.

High intelligence is obviously also a family inheritance. What did your parents do in the U.S.?

In Cleveland, my parents immediately enrolled in English classes and learned the language. Our mother stayed home with us for a longer period, while our father attended a machine operator course and at the same time started working with typewriters: he manufactured Hungarian-character typewriters, soldering the type heads himself. After a while, he was told that if he was willing to sell ten machines a year, the factory would make the typewriters with Hungarian characters. Initially, this was his source of income, but after completing the course, he was a very sharp mathematician, and he was hired by General Electric.

On the east side of Cleveland stood many corporate buildings of General Electric, including one where physicists, chemists, and mechanical engineers worked on the upper floors, while the ground floor had an experimental laboratory where everything conceived on the upper three floors had to be tested and built. My father held a so-called creative position there, which he loved very much. In contrast, my uncle worked on the assembly line just to support the family, and devoted all his energy to the local Hungarian community. My aunt knew four languages—Hungarian, French, German, and English—and if anyone at the company came across a scientific article they wanted to read, she translated it for them. So they worked at the same company, but in different departments and positions, commuting together in one car…

Your parents also set up their own import-export company…

Nádas Business Service initially dealt with sending so-called IKKA packages, which consisted of care packages—including scarce goods or money—to relatives remaining in Hungary in exchange for hard currency. Later, my father opened a bookstore in our home and founded a publishing company for Hungarian children’s books, among others. There were workbooks that I compiled at my father’s request. For decades, my father also printed the yearbooks of the Hungarian Congress, the Hungarian Chronicles, edited by János and Rózsa. The siblings worked very closely together, also on this project. The business eventually expanded, selling all sorts of items from Hungary, such as handicrafts and Herend porcelain.

In addition, my father was probably the largest importer of pottery made in Hódmezővásárhely for some time. A lifelong memory is visiting the workshop in Hódmezővásárhely thanks to this business, upon my first visit to Hungary. Our parents gave each of us a trip to Hungary as a gift after finishing university. Gyuszi went with my father, I went with my mother, and Jancsi went with friends. We traveled in 1968, and we spent four weeks in Hungary; my mother’s siblings were still alive, and I got to know my cousins, with whom I have stayed in touch and always visit when I go to Hungary. On that trip, my father asked us to place a large order at the Hódmezővásárhely workshop. They let us go back to see the workers shaping the clay, putting it in the kiln, taking it out, and smoothing it, applying the base coat in different colors, drawing the patterns, and finally applying the glossy glaze. The workshop closed in 1991, but I still have some pottery from there that I occasionally give as gifts.

Did you participate in events of the Hungarian Society as a child?

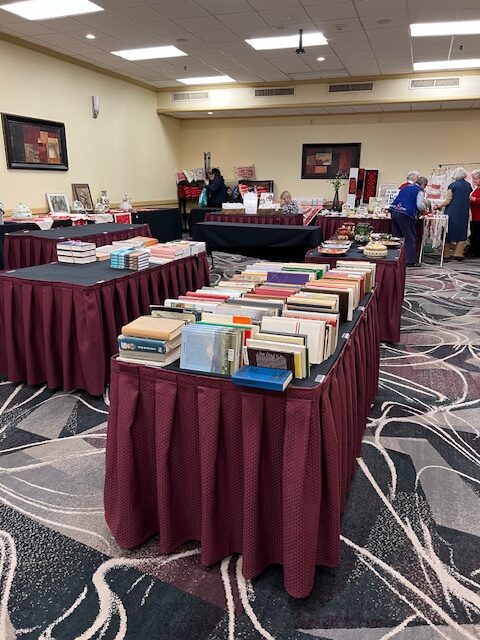

Yes, we always participated in its meetings and monthly programs. We were the young people who dusted and set up the chairs. Sometimes we recited poetry, and of course, we took part in the two-and-a-half-day Thanksgiving weekend Conference, which always ended with a Hungarian ball, as it still does today. Initially, we didn’t attend the balls, just helped during the day. I, for instance, helped my father with the book exhibition. When my uncle passed away in 1992, I inherited the exhibition, which I managed until last year. In the meantime, I expanded it, selling pottery, paintings, and various Hungarian objects besides books. I tried to attend the monthly board meetings—that meant a three-hour trip from Ada. Recently, I stopped, and as of this year, I’m no longer a board member.

Did your mother work and/or participate in all these Hungarian events and projects, or did she ‘only’ provide the family background?

My mother mostly stayed in the background, but she helped a great deal. She typed all private correspondence, business, community, and official documents with carbon copies. She also did a lot of housework as we often hosted large Hungarian gatherings. This reminds me of a story: my mother didn’t allow me to cook and didn’t really teach me, but she asked me to bake, because she didn’t have time for that. Once, when I was in high school, on a Sunday afternoon, my parents went to a Hungarian gathering, and I decided to bake a Dobos cake, following a cookbook with mathematical precision. When they returned, my mother rushed into the kitchen and asked what we could serve to the soon-arriving guests. She could hardly believe her eyes, and all the guests flocked to the kitchen to admire my first Dobos cake. Returning to my mother’s professional life, we were already in college when she was asked to work at a bank. She loved it: finally, she had her own life, was professionally recognized, and earned her own salary. When my father retired at 65, she stopped working a few years later at his request, but later regretted that decision, since she was only 53 at the time.

Were you able to work as a math teacher alongside your busy husband?

While András was teaching at Indiana University, I also enrolled in the Hungarian department, so I earned a master’s degree in Hungarian as well. My friend Márti, whom I mentioned earlier, earned a doctorate in French and worked at Ohio State University. Someone, Leon Twarog, suggested that since there are many less commonly spoken foreign languages in the U.S., but no one to teach them here, textbooks and audio materials should be published so that people could learn the languages independently, autodidactically. I participated in this project as well; Márti and I produced many tapes, and we have two or three textbooks published by the university, which were later used in many places. In fact, one summer I even taught Hungarian in Columbus, OH, at Ohio State University. The organizers of the Hungarian program there also invited me to give a lecture on folk customs, due to my previous lectures given by ethnographer Tekla Dömötör in Hungary. I even visited the White House! When Péter Újvági, a congressman from Toledo, OH, and a key figure in the local Hungarian community, called András—he knew him since my husband had written a book about Toledo’s Hungarian quarter—and said that Hillary Clinton had toured Europe and wanted to report on her trip to an invited audience in the White House. Péter and colleagues wanted all those who valued their European roots to participate in the event, so he asked András if I’d like to attend. That’s the only time I went to the White House, where I had a photo taken with Hillary.

How did you meet András, and how did your Hungarian community and professional life develop after your daughters were born?

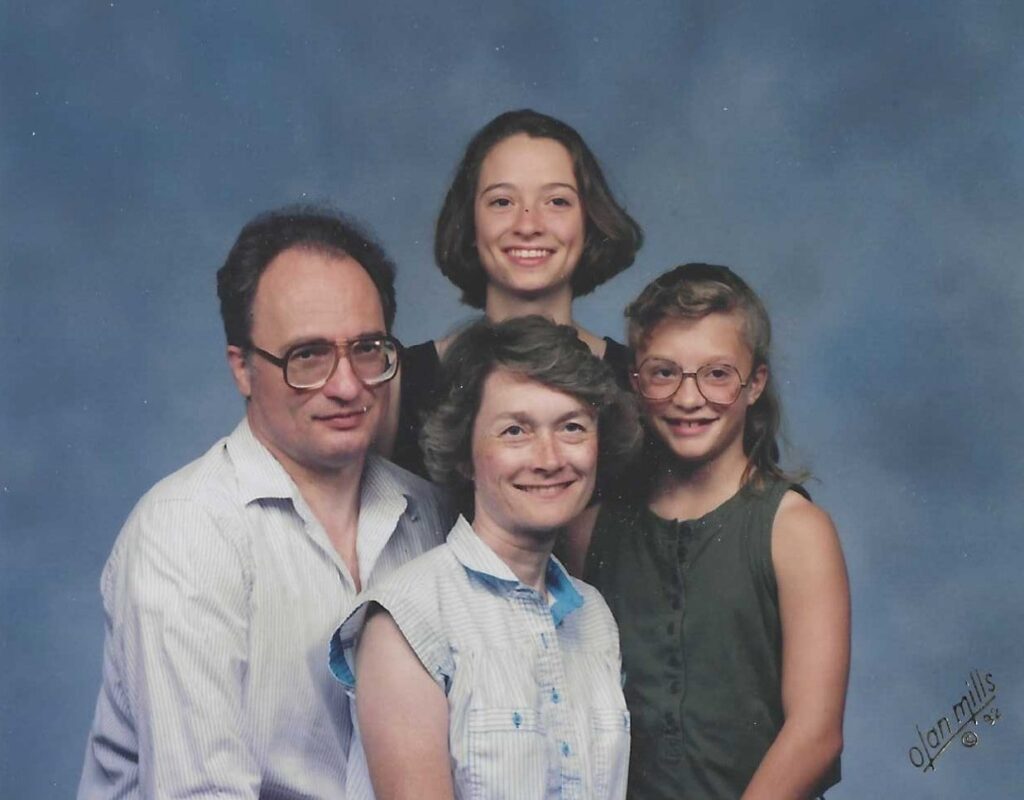

In the fall of 1968, András attended a Cleveland tea event with his friend Gyurka Csomai. At that time, I still lived in Lakewood and attended university, while he was teaching at Ohio Northern University (ONU) in Ada, OH—a small, but nationally recognized private university with its own law, engineering, and pharmacy schools. We met a few times, fell in love, and although I didn’t see him for a few months during the summer, because he went to visit his family in Connecticut, we had already set our wedding date, which took place in August 1969, less than a year after we met. I moved with him to Ada and started teaching math at a nearby small-town high school. I remember that on the first day, a student came to my desk looking for the teacher…I was 22 but looked 18…I taught there for five years and stopped teaching. Then Csilla was born in 1978, and Anikó in 1980.

In 1982, we moved to Budapest, Hungary, for the fall semester, where András taught as a Fulbright scholar and I attended Tekla Dömötör’s ethnography lectures for half a year. The girls were two and four years old. A few years later, I was invited to be an adjunct professor in the Mathematics Department at ONU, where I taught for 12 years. Ten years later, we returned to Hungary, this time to Debrecen, where I filled a vacant English teaching position at an elementary school where our 12- and 14-year-old daughters were learning. Our time in Debrecen left a strong impression on our school-aged daughters: when Csilla had to choose a semester abroad, she chose Debrecen. This was important because, as I mentioned, there was no Hungarian life in Ada outside our family. The girls didn’t want to attend the same university where we worked: Csilla followed her father’s profession and studied political science in Indianapolis, while Anikó studied organizational development, also in Indiana. Csilla settled in Houston, TX, and Anikó in Chicago, IL.

I eventually earned another university degree in psychology and a master’s in theology, specializing in counseling. In 1995–96, when our daughters were in high school, I returned to university, and half a year later, I started working at an elementary school as a counselor twice a week. That same year, I taught half-time in our local high school, and in the second year, I was offered a full-time math teaching position, which I accepted, giving up my job at the university and counseling. When asked why I earned a counseling degree ‘for nothing’, I replied: ‘As a teacher, every day I use what I learned there; it has made me more humane, understanding, and attentive with children.’

When and why did you move to Texas?

In 1997, András and I divorced, and I lived alone in Ada. I retired in 2013. I stayed one year longer than planned, because the juniors begged me to teach them for one more year, so I stayed. I continued substituting for five years. In 2017, Anikó called to tell me that her husband was being promoted and they had to move from Chicago to Texas. They chose Houston over Dallas because Csilla had been living there for 15 years. After I retired, I spent three–four days a month in Chicago with my grandchildren, and it became clear: if I wanted to continue seeing them, I’d have to move to Texas, too, which I did in March 2018.

I tried to connect with the Hungarian community in Houston, and we attended their events twice, but everything stopped when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. My daughters are very busy, and neither of them has a Hungarian husband. Since we didn’t live in a Hungarian-populated area during their childhood, they didn’t really develop Hungarian friendships–even though their parents were devoted to the Hungarian cause. For those living in Hungarian communities, various local Hungarian organizations are easily accessible: the church, scouting, weekend school, folk dance, etc., where they can regularly meet. Our daughters were left out of this, and I also feel a bit disconnected at ITT-OTT, because I don’t belong to any local Hungarian groups. Of course, I know most of the participants, and I was much closer to those who are no longer present or alive, but with the current members, my involvement is limited…

Now let’s turn to the MBK, of which you and András are essentially founding members, but, like your parents, while András was active in the foreground, you worked more in the background.

When I met András, the initiative for thinking and corresponding about the Hungarian diaspora life had just started, initiated by him, Gyurka Csomai, and Lajos Éltető. As soon as our wedding was over, my task was to type the submitted writings on my father’s Hungarian typewriter onto stencils. (We bought a mimeograph machine so that we could make copies.) Then we mailed the approximately 25-page publication each month. In 1972, we had our first in-person meeting in Hereford, PA, where I served as secretary. Seeing how much work it took to organize such a meeting, the following year we only invited the leadership to our house in Ada, where many more attended than we expected. Seeing the high demand, next year we organized the conference again at Chautauqua Lake, NY. After the central building burned down two years later, we looked around at state parks in Ohio and found Lake Hope. We edited the monthly newsletters until the mid-1990s; I participated in that work throughout. I also served as secretary for the conferences for a long time and organized the children’s programs for 15 years, playing with them in our cabin during the morning sessions and preparing them for a performance at the end.

How do you view the future of MBK, which has been characterized by many ups and downs and new beginnings?

The initiative was extremely valuable and gap-filling. My uncle, however, would have preferred if we had joined his group, so he asked András: ‘Why are you creating another Hungarian society?!’ He replied: ‘We have different ideas; we would like a forum for our generation as well, where we can freely exchange them.’ My uncle was a bit upset with me. My parents once joined and sold books, but my uncle didn’t like it, so they didn’t come again. As far as the future is concerned, I think—and András and I don’t completely agree on this—that young people should decide for themselves why they want to gather and what is important to them. It’s no surprise that it’s not so important for them to carry on our baton, because earlier we ourselves were not willing to take over the baton from the Hungarian Society…I believe that anyone who comes here values Hungarian identity, including young people present here, and we should appreciate that. This is a week nobody forgets once they participate. Back in the day, it was the first week-long Hungarian event in the United States that the whole family could attend. The children’s program started because parents wanted to attend the lectures. That’s why it’s so important that it continues, and that’s why I committed to it for so long. But a person must also know when to stop. Last year, I turned in my resignation from the board in MBK, and I’m doing the same in the Hungarian Society, but I still haven’t come to a full agreement with my brother Jancsi about it…

If you believe that young people should take over and continue MBK in the way they wish, you shouldn’t expect them to follow the founder’s ideas?

Indeed. But I also want ITT-OTT Conferences to be continued in Hungarian and to retain their cultural character. They should continue inviting guests from both the United States and Hungary, as they enrich and diversify the programs. Maintaining the framework is important, but we shouldn’t cling to our own ideas. Older participants should acknowledge that they can attend even without a desire to perform. And if they do give a lecture, it shouldn’t be solely for their own enjoyment, but offered in a way that is interesting for the audience as well.

‘I’m very grateful to God for all this, and every morning I keep asking Him to show me who I can help that day’

The generational change in membership and leadership is always a difficult issue for every organization, including the Hungarian Congress as well, and it depends largely on the older generation. My brother Jancsi also sometimes clings tightly to his own ideas and to his old ways…Last year, a young man who helped transport my books to the Hungarian Congress would have gladly taken them over, but that was not Jancsi’s preference. He also decided not to throw away many old publications I had. Since moving to Texas, I want to sell my house in Ada, so I’ve been sorting papers for years. I rented a storage unit for two years in Cleveland, but when it ended, I no longer wanted the responsibility. The Hungarian Society has always been led by members of the extended Nádas family, but Kuni and János can’t lead forever either; they also need to find their successors. I see some challenges in that, but it’s no longer my concern.

Last question. Since your faith is very important to you…Why and what related volunteer work have you done for years in Transylvania?

When bishop Béla Kató visited the ITT-OTT Conferences in 2004, I asked how I could help, because he had previously told us: whoever wants to help should not just send money, but also commit their time—that is, visit them in Transylvania. As soon as he learned I was a teacher, he told me that the Youth Christian Association (Ifjúsági Keresztény Egyesület, IKE) has several summer camps in Algyógy (Geoagiu, Romania), including English-language camps where a team of eight individuals came from an English-speaking country so they could speak only English with the children…At first, I went there alone to see what it was like; I also taught and participated in several leadership camps. When I returned, our pastor in Ada asked me what could be done to help. I corresponded with Pastor Tibor Nagy and his wife, with whom I stayed for a few days during that first summer. I then organized an eight-member adult group from the Ada congregation, with whom we built a laundry room in the parsonage and installed central heating in both the parsonage and the church. After that, the others returned home, and I stayed for the language camps.

One year, children came from an orphanage, and the organizers asked us to try to connect closely with them. One boy and I became so close that he has called me his American mother ever since. Later life brought him to the U.S. as well, and we have maintained contact; they even attended the ITT-OTT. After we finished the camps in Transylvania, camp leaders took me to Transcarpathia, Ukraine, where they held similar camps for two years. There, too, I formed a close relationship with a young man, and about four or five years ago, while on some assignment here in the U.S., he contacted me. These camps didn’t continue after the COVID pandemic. Csaba and Ilona Veres now run a mission in a small village that never had a church, and are trying to establish one.

Returning to my faith, after confirmation, I taught Sunday school until I got married. When we moved to Ada, we traveled so much with my husband that I could only rarely attend church. However, when I visited Cleveland, I always went to the Hungarian Reformed Church of my childhood. Csilla’s first baptism took place at the ITT-OTT Conference, and her second at the Ada congregation I joined. Around 1981–82, I heard in a sermon that God doesn’t only call us to attend church on Sundays, but this is an important challenge in our everyday life. Soon I became a ruling elder; I was the first female elder, which not everyone appreciated, neither in the church nor at home…Over time, I became the chief elder, but when the pastor changed and moved in a new direction, I resigned. Afterwards, we attended several churches for a few months and eventually settled in a Presbyterian church where we felt very comfortable; I became an elder there as well and taught in the adult Sunday school. My daughters have always joined me and later found their own faith communities at their universities. Both of them have a very strong faith and are raising my grandchildren accordingly. I’m very grateful to God for all this, and every morning I keep asking Him to show me who I can help that day…

Read more Diaspora interviews: