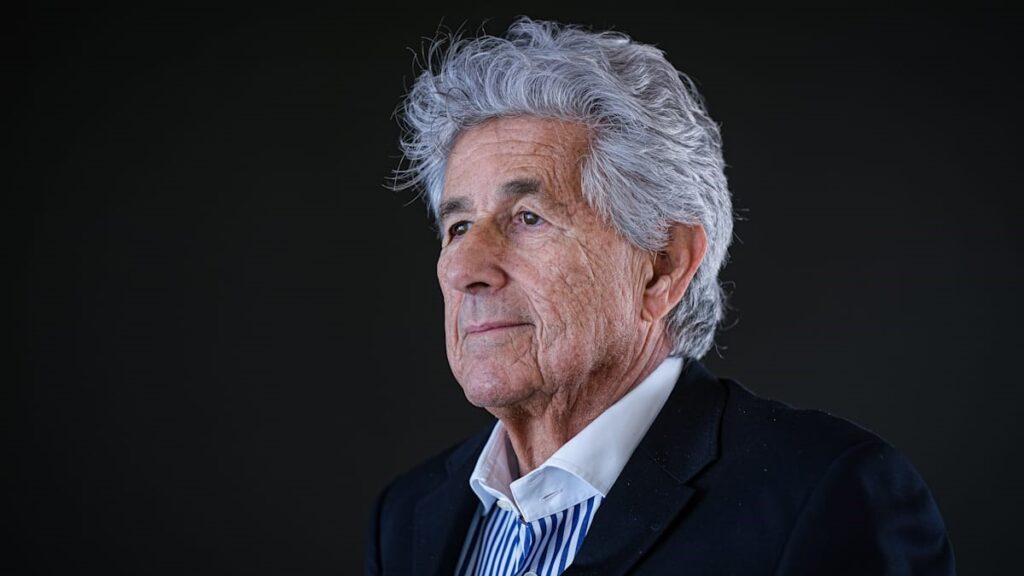

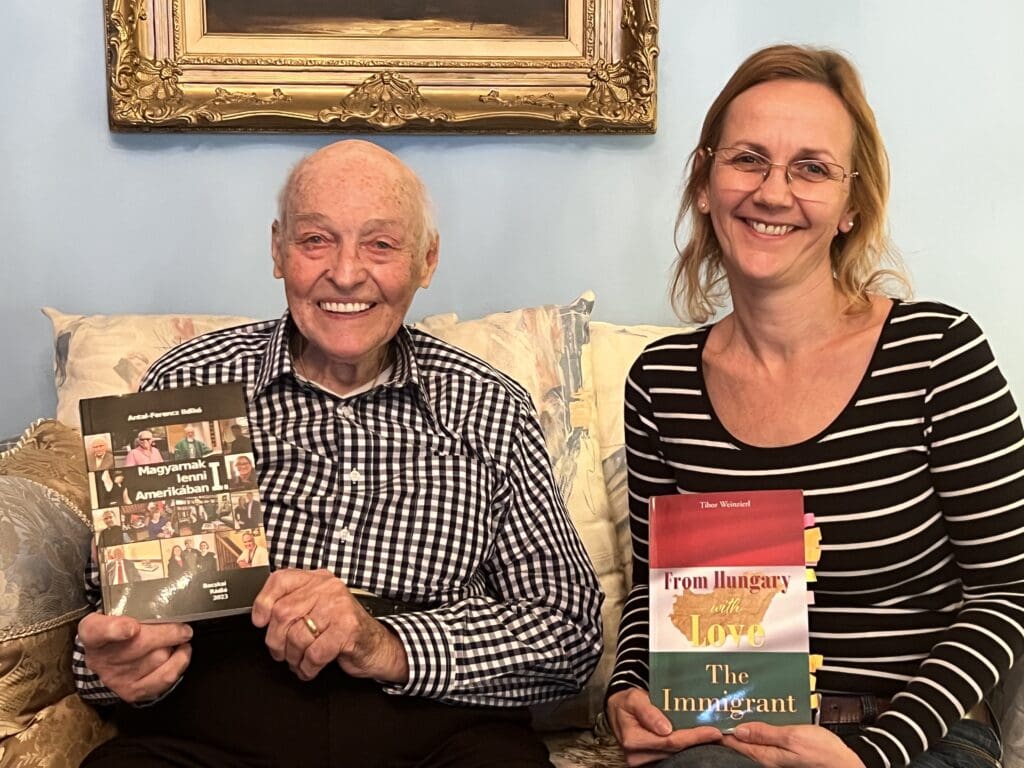

I first heard about Tibor Weinzierl when Hungarian friends in the Boston area brought his recently published autobiography to my attention. I have since read the book and visited him at his home, where we talked about his adventurous life in Hungary, Canada and America, touching on many details that are not included in his autobiography.

***

Let’s first talk about your family heritage. Is that where the singer-musician talent, your work ethic and your deep faith come from?

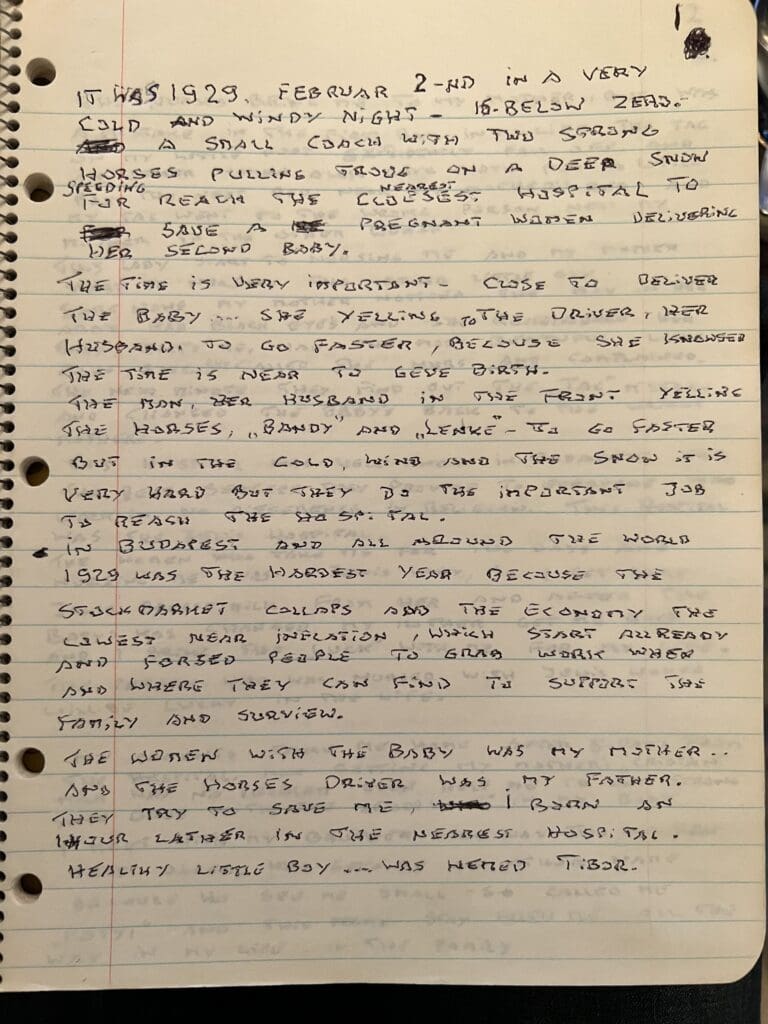

My father was an electrical engineer, and he wanted me to follow the same path, but I was more interested in sports and music. But the love of music was also present in our family: we had a piano, as every other family around us at the time, and my father also played the tympanum (a percussion instrument) at the Opera House. His sister had her own music school, attended by 40–50 children, and I started violin lessons there at the age of five. Because I had very good hearing, I sang Ave Maria with the church choir in Rákosszentmihály (today part of Budapest, in the 1930s an independent small town) when I was eleven, because the choir leader noticed me. In our house it was never acceptable to be tired; we were always doing something, and if something didn’t work out, we’d start doing something else. My father often said that our life is like a wheel, and after the downhill there is always an uphill, but you must work for the latter. He and his brothers and also my brother, Oscar, worked all the time, too. As a Piarist student in the emerging communist system, a few years after World War II, Oscar was not admitted to the university he had successfully applied to, so my father went to the university and slammed the table. Consequently, my brother was taken to a forced labor camp, where he broke stones and built roads. After a year, he was released and eventually could study law, later becoming a judge. Everywhere I looked, I saw how my family members worked their way up to where they were. Later on as an emigrant, I always wanted to do my best, not to be sent away.

But to achieve your best, you must love what you do.

If you don’t love your job, you can’t perform at 100 percent. So, it’s always been on my mind: if I’m not good at what I do, I’ll quit and do something else that I love. Wherever I went, I loved it and I was loved. My bosses saw that I put my heart and soul into my work, so they treated me like a family member. I worked in one place for many years: at Café Budapest for ten years, at Boston Beer Works for thirteen, at Bertucci’s for six. It wasn’t easy, but with God’s help I always found a job that brought me joy. As far as my faith is concerned, I was brought up that way. I went to Catholic school, and my whole life was spent starting with prayer in the morning, working, and ending with prayer at night. Even today, every morning and evening I give thanks that I have food. It’s natural for me. But I guess it’s natural for others, too, because when they get in trouble or see others in trouble, people say without thinking: ‘Oh, my God!’

It’s impossible to summarize the two and a half years that you spent as a teenager in World War II and then in the Russian prison camp (one has to read your book for that); but we can’t avoid the topic as it was a life-defining experience. What was the most difficult thing for you?

When the Russians came into Orlick, where the Americans left us, we had to walk with them all the way to Strakonice, day and night, passing burnt cars and dead bodies. It was very exhausting, but even more so mentally: it was very difficult for me at fifteen to understand why all this was happening. Even though the war was over and prisoners of war under the age of eighteen should not be kept with adult prisoners of war, this happened to us for a year and a half, and we did the same hard physical work in the same horrible conditions just like the adults. The work in the camp was hard, but I got used to it. I even found many things funny, which in hindsight were obviously not funny at all. For example, when asked who could swim, I was happy to volunteer. They took me down to the Moldova river, where I had to place a small mine in the water (close to the midpoint of the river) and then swim away quickly because they started shooting at the mine. About a hundred meters down they put up a big net, and that’s where the blown-up fish was caught – that’s how the Russians fished. It almost cost me my life, but I laughed at their stupidity. It also seemed like a fun thing to do when I had to empty heavy bags of sugar and someone advised me to grab the two corners of the sack, shake out the remaining sugar afterwards, take it back to the camp and exchange it for something else. It was less fun having to sleep on the bare concrete, but I quickly made a bed for myself out of a discarded scrap door and put two bricks underneath in one end to make it higher where my head would rest. I tried to get rid of the bugs by covering myself with paper at night, and when they came, I would hear them and shake them off. But I couldn’t deal with lice myself and disinfection was always very painful. But the worst was the humiliation. So I started every morning with a prayer: ‘God, please help me to have a good day today, no beatings or humiliations’. We lived in inhumane conditions, but everyone in our small group survived. We didn’t even try to flee; we knew the Russians would shoot us on sight. It was hard, but I kept thinking: what about home, when will I get home? Captain László Molnár (Stufi) kept our hopes alive, telling us every week that he was working with the Red Cross to get us home.

This situation, however, helped you later to get your US citizenship, right?

When I moved from Montreal to Boston, the lawyer of my employer, Dr. Sándor Szabó, found in the Pentagon archives the document that we signed on 10 May 1945 in Orlick: if a war broke out against the Russians, we would fight in the front line as part of the US Armed Forces. I was summoned to the Kennedy Building, where three FBI agents spent several hours questioning me, particularly my post-war ordeal, and I was granted US citizenship in October 1981. Shortly afterwards I met the then Governor Edward King and received my 56 medal from him.

Because you fled Hungary in 1956. What are your memories of that time?

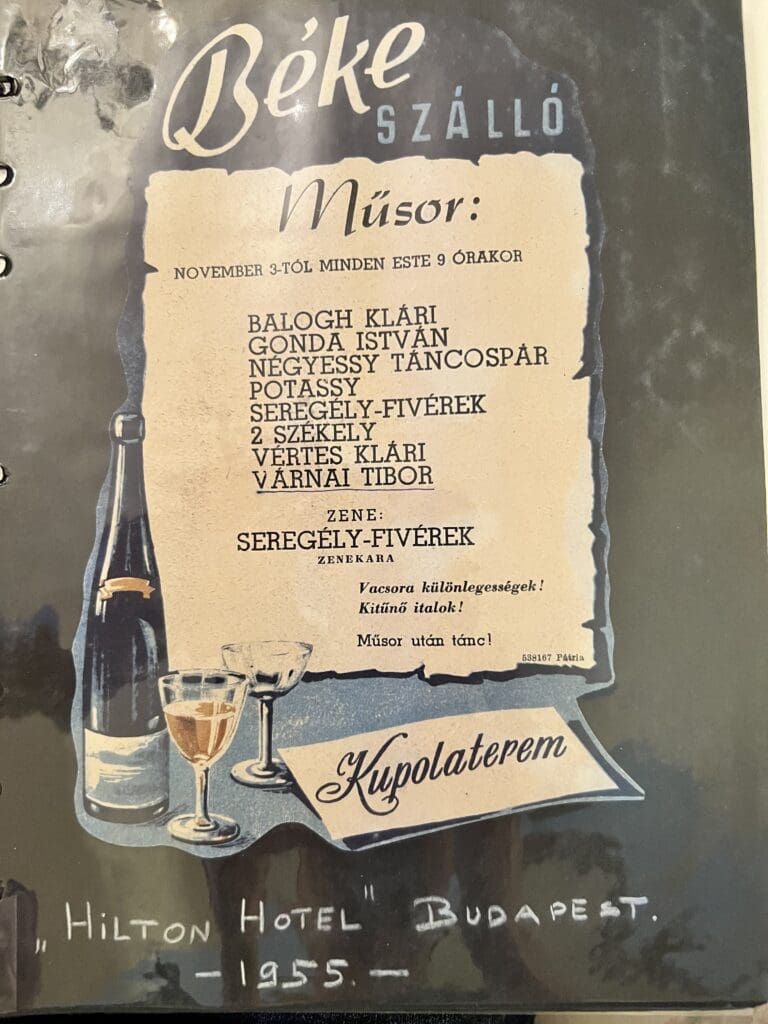

When we intercepted a Russian soldier on the streets of Budapest, we took him down to the basement of a house and asked him where he thought he was, and he replied: Germany. These soldiers were drinking alcohol from the lamps, that made them completely stupid, they didn’t know what they were doing and were shooting without thinking. I flee Hungary mainly for personal reasons, but before that I had also experienced how a communist dictatorship works. My retired army officer father—who was captured by the Red Army in World War I, but managed to escape and rode behind Miklós Horthy, when the latter marched into Budapest in November 1919—was kept under constant surveillance. Once at three in the morning they broke into our house and tried to plant a gun, which my father luckily noticed and chased them out. Our surname was blacklisted, which is why I had to change it from Weinzierl to Várnay when I started singing at the Hungarian Radio. Also, I was banned from singing for six months, because of singing a song that was previously cleared by the censors. After that I got fewer and fewer opportunities on the radio, so I started performing in clubs. The 1956 revolution came ‘just in time’ for us, because a nice lady, Gyöngyi, asked my help to prevent her two-and-a-half-year-old son from being taken away from her by her former husband, Ferenc Buzás, an astute communist. She asked me to help her and her son flee the country after the revolution was crushed. I fell in love with her, married her, and we fled as a family across the cornfields to Austria. We arrived in Canada on 1 February, in 1957. We got along well at first, we even worked together as a duo. The problems that eventually led to divorce started when, a few years later, she started to bring her parents from Hungary and her sister’s family from France, and I had to support them financially.

You also received recognition for helping erect the 1956 memorial in Boston. And not so long ago, the Hungarian Scouts of Boston asked you to share with them your memories of 56. How did you get involved with these organizations?

Back home, I was a member of Boy Scout Troop no. 929. During and after World War II, scouting was disrupted and shortly after dissolved by the communists. When I came to Canada, I was already 27 years old, and had to work somewhere else every weekend. In Montreal, I was in touch with the Hungarian community, but couldn’t commit to attending meetings or events regularly. In Boston, I also got in touch with the local Hungarian association and from 1972, I served as the secretary of this association for two years, organizing regular programs and delivering a joint concert with soprano Magda Füzessy at Boston University. When the idea of the 1956 memorial came up, I raised the most money for the statue, $6,000 from friends and politicians—that’s why I got the mentioned recognition. I’ve heard about Hungarian scouts in the Boston area only in the 2000s. But by then, my second wife, Doreen became seriously ill, and I had to stay at home with her because I never knew what would happen to her in the next half hour. After she died two years ago, I got in touch again with the Hungarian community.

Let’s go back to your musical career, which started after the war, but was flourishing in Canada (Quebec) and then in the US (Massachusetts). What was the key to success?

After the war, I attended the Academy of Music in Budapest, where I met Zoltán Kodály, a leading Hungarian composer and teacher of the last century, who was one of my teachers. In 1950 there was a talent contest in Hungary, which four of us won, including Márta Záray, and that’s how I got on the Hungarian Radio. In Canada, while still in the refugee camp, I met Steve Ness, a music industry impresario who later helped me to get many good assignments. But first I had to learn the language and support my family, so I did all sorts of jobs: I was carpenter assistant, hotel assistant, tobacco leaf picker and baker assistant. In between, I learned French and English simultaneously, practiced the violin and then traveled across Quebec with my wife, who performed under the stage name Pearl. We staged a 35-minute show, ‘warming up’ the audience for other performers. Between songs, Gyöngyi danced Hawaiian, South American and gypsy dances. An agency organized our performances. That’s how I lived the ‘nightclub life’ until 1969, when I moved to Boston with my second wife, Doreen, to work at Café Budapest.

How and why did Edit Bán, the owner of Café Budapest, contact you?

In 1967, the World’s Fair was organized in Montreal and she heard me singing and playing there. She invited me to work for her, but at the time I’d just started a two-year contract, so I couldn’t go to Boston until the very end of 1969, and then worked for her for ten years. She wanted gypsy music, so I took a gypsy premier violinist and a ‘cimbalom’ (hammered dulcimer) player with me. There was no gypsy music offered in Boston before us. Our very first performance was a great success, and the Boston Herald newspaper enthusiastically welcomed us to the Boston art scene. Celebrities—politicians, musicians, millionaires, Hollywood stars—who came to visit Boston usually came to eat at Café Budapest, which was considered the best restaurant in town at the time. Senator Ted Kennedy, for example, was there at least once in each month. Our music was special as it made people feel like they were in Europe and no one played the cimbalom in the US at that time. István Csikós, whom I had brought from Montreal, was admired and photographed while playing. Everything went very well for the first six months, but then Csikós suddenly went back to Canada for family reasons, and three months later the violinist Giulio Whiskey also left. I then joined up with Ellen White, who was a very good pianist. We became the best duo in our genre in the country, but because she had a cocktail in each of the four intervals, by the time we got to the end of the show at midnight, she was playing the piano very slowly… Later I teamed up for a long time with another very talented pianist, Eugene, who grew up in the Kyrgyz Republic. He was so talented, he could play anything he heard me play, even the most difficult pieces like Monti Csárdás. He once won the second prize at a music festival in California.

After Café Budapest, you worked in many other places, but less and less as a musician, more as a manager, maître d’, or sommelier. When and why did you put the violin down?

After ten years at Café Budapest, we felt we had to move on, because as much as Edit Bán loved us, she wouldn’t raise our salaries. First, we played in Warner’s Restaurant and sold a lot of our records there, too, then in the Hungarian-owned Csárdás and Blue Danube restaurants. When the latter closed, Eugene and I separated, and then with two friends we opened a restaurant called Red Pepper. I played music on weekends there; we had a trio with a very good drummer and a guitar player. The 120-seat bar was always full, and business went very well; we were able to sell it for four times the acquisition price two years later. Afterwards, I worked at Bogie’s Place and later at Boston Beer Works, as a sommelier and a maître d’, and I was also singing, with a friend accompanying me on piano. Since I developed arthritis, I had to put the violin down.

Your last job was at Bertucci’s at the age of 81 starting as their oldest employee ever. You left after six years, due to your wife’s illness. It’s hard to imagine all of this with a European mind. Was the reason for working then still to support the family?

I worked because it was in my blood: I didn’t want to stay at home all day, just sitting and watching television.

I felt too young for that. When I quit, they didn’t believe I was really leaving them. For me, it was a dream job: as a maître d’ (head of dining-room staff) I welcomed the guests, showed them to their seats, kept them company and they loved me, and it also boosted the business. I got thank-you letters from them all the time. It was one of the happiest times of my life, but unfortunately Doreen started to fall more and more often because of dementia. Caring for her became my last and biggest ‘job’.

You wrote a lot about Doreen, your beloved (second) wife, detailing the last very difficult years when she was finally placed in a nursing home. It is impossible to present your happy 58 years together shortly, so let me ask: what are your fondest or saddest memories of her?

When you entered this room, you were surprised to see that my Christmas tree was still up at the end of March. That’s because before my wife went into the nursing home, a sad incident happened: one night she ran out to the street in her nightgown and rambled there until I found her and brought her back to the house, almost frozen. When she calmed down, she looked at me with a clear look next to the Christmas tree and said: ‘I love you very much, Tibor, I will always love you.’ The Christmas tree has been there ever since. And everything else is just as it was before she left. When I shave, I talk to her photo. What hurts the most when I think about her is that I had to lie to her so many times. We used to live in a much larger apartment and whenever she thought about it, she would always ask me to move, she would even say in Hungarian: ‘I hate living here,’ and she would get upset, so I had to reassure her many times that it was okay, we’d move. Similarly, at the nursing home, she often asked me why I was leaving and when I would bring her home, and I replied to her that I had to do something, but I would come back to her soon. It seemed like deceit to me, and it bothered me for a long time after she died. I also felt guilty about the nursing home, even though I knew I had to place her there, because I couldn’t take care of her anymore. I tried to visit her as often as I could, even during the Covid pandemic, and tried to bring as much joy as possible into her last years; and also for her eighteen companions.

You shared a lot of data off the top of your head, and in your book, you often detail events by the day, even by the hour. What is the daily routine that keeps you so fit even now?

Five years ago, when my wife’s condition was getting worse, she kept asking me: what about the book?! So, at the age of 90, I started putting my notes together, wrote down everything I could recall, and then I gave it to a publisher. I had already begun writing notes earlier, starting from the time when I was two and a half years old, sitting on the legs of Baden-Powell (‘Bi-Pi’), the founder of the Scout movement, at the fourth World Scout Jamboree in Gödöllő in 1933. I also have a group photo from my high school and I know many of the students by name. I’ve always found a way to remember the names. If I can’t recall a name easily, I start saying the alphabet out loud and suddenly the name comes back to me. My brain still works well… Every day I open the windows for two or three hours while I prepare my breakfast. If I need something, I drive to the nearby store; I often go to the Senior Center, they have two–three shows weekly. I’ve been doing my few minutes of exercise three times a day for many years. There’s always something to do.