Ah yes, our stately European Commission, that venerable body to which we have, over the years, entrusted ever more strategic tasks, under the assumption that doing so would make Europe stronger. And behold, the Commission has now found its master concept: derisking.

The term emerged as a softened version of the American idea of decoupling from the first Trump era: the United States’ attempt to sever its technological and economic ties with China. To European ears, that sounded a bit too drastic; yet, naturally, Europeans wished to imitate America all the same.

Thus came derisking: not a full rupture with China, but a selective freezing of strategically sensitive connections under the guise of risk reduction.

Sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? Who could possibly object to reducing risk?

Only, derisking does nothing to reduce Europe’s geopolitical exposure. It merely chains down the Europe–China relationship, narrowing the EU’s strategic room for manoeuvre, to the quiet satisfaction of our adversaries in the Kremlin.

Above all, the policy of derisking deepens Europe’s asymmetric dependence on Washington—a risk in its own right. This past summer, the EU found itself negotiating from a position of weakness with Trump, in no small part because it had failed to deepen its ties with Beijing in recent years.

Coastal America has become our overpowering point of orientation: for our military security, our financial infrastructure, our social media, even our public discourse. And Washington knows it, exploiting this one-sided dependency through its hard-edged trade policy, designed to enrich itself at Europe’s expense.

Chained Down

But how, one might ask, does derisking put the Sino–European relationship in chains? After all, it merely signals a wish to engage a little less intensely. Nothing drastic. You still cooperate, only at a lower temperature: not because you despise the other, but because you find her a little unsettling. Sensible enough, one might think.

No, derisking is a ruinous premise. It works much like in an early-stage romance: the desire to further deepen the relationship is essential to its health. The moment you inform your partner that you seek something less meaningful, you have, in all likelihood, set the beginning of the end in motion.

‘Diplomacy, too, needs a horizon: something to move towards together’

Great powers are more forgiving than lovers, for the options in international politics are fewer. But diplomacy, too, needs a horizon: something to move towards together. Tell the other side you want to be less connected, and you drain the energy out of the relationship.

That very loss of energy now afflicts the bond between Europe and China, a partnership whose potential remains tragically underestimated. China has much to offer Europe: it is the world’s leading industrial producer and technological innovator, and heir to one of the most luminous civilizations in history.

Moreover, the EU and China share a common responsibility. As America’s sphere of influence collapses under the weight of domestic political polarization—a process that manifests outwardly in economic bullying and, more broadly, in destructive disorder—it is precisely the EU and China, the two largest economic blocs after the United States, that remain indispensable to whatever international stability can still be preserved.

Cosmic Struggle

All this may sound strange to liberal Western ears, accustomed as they are to perceiving world politics as a cosmic struggle between the light of the liberal-democratic West and an authoritarian darkness. Within this worldview, China is ‘authoritarian’—and therefore a potential source of disorder—while liberal Westerners and the European Union are, naturally, the embodiments of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’. For many reasons, that is a simplistic, self-centric, and self-flattering picture, but this is not the place to deconstruct its political metaphysics.

Let me instead sketch an alternative contrast, one that is far more relevant to the current international situation: Trump’s personalism versus the bureaucratic approach of the EU and China. President Trump turns international politics into an arena of deal-making—deals between the leaders of great powers—whereas the EU and China are vast modern bureaucratic empires, comfortable within carefully elaborated institutional frameworks.

Of course, the Americans—and especially the Trumpists—are far cooler than the bureaucrats of Brussels and Beijing. And should Trump succeed in brokering a durable ceasefire in Ukraine, we Europeans ought to be sincerely grateful to him. But still: world order, the orderedness of international politics, requires bureaucrats.

In Chinese vocabulary: the EU and China are called upon to lead with Humane Legitimacy (王道, wangdao). Where such legitimacy is absent, there arises Arbitrary Power (霸道, badao). Badao manifests itself today in the domineering impulse of the Trump administration, which seeks to exploit weaker states and leaders through trade wars and other instruments of pressure.

Naturally, there are differences between European and Chinese conceptions of international order, yet these are bridgeable. Those who vehemently deny this must explain why China’s outlook on global coexistence—including its views on trade, financial infrastructure, sea routes, peaceful development, and the modern state’s monopoly on violence—should be fundamentally incompatible with that of the EU.

‘The EU may not wish to resemble China, yet, in many respects, it does’

Yes, there is a regime difference, but let us not exaggerate it. The European Commission and the Chinese party-state are both vast modern bureaucracies, each striving to develop peripheral regions and flying the banner of ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion’, while each imagines itself to be the moral centre of political goodness. Do with that what you will. The EU may not wish to resemble China, yet, in many respects, it does.

Urgent Strategic Importance

For the European Union, rapprochement with China is a matter of urgent strategic importance. We need friends more than ever now that Russia has invaded Ukraine and the devastating war drags on. The mere fact that the Kremlin would grow nervous at the prospect of a deepened relationship between Europe and China says it all.

At the same time, both the EU and China find themselves under parallel pressure from Washington’s economic power politics—a battleground on which Europe is far weaker than Beijing.

Beijing holds powerful cards. China has responded to America’s steep tariffs on Chinese goods by restricting the export of processed rare earths, which are essential for satellites, solar panels, electric vehicles, semiconductors and missile-guidance systems. China dominates both the mining and the refining, and is now letting American importers get stuck in the machinery of its export controls.

What goes around comes around. Washington escalated its trade war against China earlier this year, and is now reaping the consequences.

Europe, however, is feeling the pain almost as acutely. Geopolitical analyst Joris Teer, who has studied the issue in depth, notes that European importers, particularly in the defence sector, continue to suffer from the new Chinese export restrictions. Since the Europe–China summit in July, the situation has improved somewhat: Europe’s civilian firms now enjoy easier access through a preferential route, a so-called ‘green channel’ (绿色通道) in Chinese terminology, which indeed moves a little more smoothly.

More European supply lines should be admitted to that channel. And the channel itself could do with being a shade greener, meaning faster. Yes, Europe wants those processed rare earths! We should not be forced to absorb the blows for the reckless foreign policy of our American friends, however warmly we may regard them.

Teer observes that the reduced flow of rare earths to Europe’s defence manufacturers threatens to halt the development of a robust military-industrial base within the EU. And that base is no trivial matter: in the long run, it must strengthen our eastern flank against Russian expansionism and reduce Europe’s dependence on exorbitantly priced American weaponry.

Chinese Doubts

One might think: why not simply send a European diplomatic mission to Beijing to emphasize once more that we really are not the Americans? But there lies the rub: on the Chinese side, serious doubts persist about Europe’s strategic independence from the United States. This became clear to me once again during two conferences on Europe–China cooperation I recently participated in in Beijing.

‘On the Chinese side, serious doubts persist about Europe’s strategic independence from the United States’

Those doubts are understandable, not only because of NATO, but also because Europeans, politically and intellectually, and in their very social imagination, remain bound to a one-sided orientation on coastal America.

Moreover, China cannot take for granted that Europe’s rearmament will serve purely harmonious ends, which would be to cement a durable ceasefire in Ukraine and lasting stability in Eastern Europe. Europeans may find such Chinese worries strange, for our prevailing self-image is that of the great peace dove. Perhaps we have not always been so, but today we embody peace itself, or so we say. Beyond Europe, however, the perception is rather different.

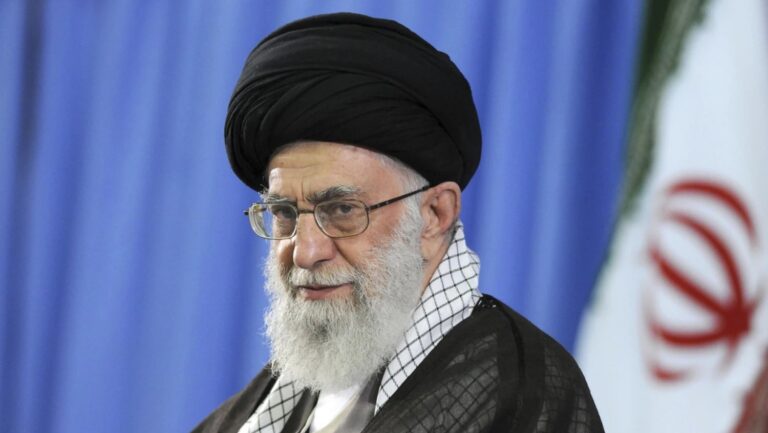

Most jarring is the recklessly ideological tone of EU leaders, among them our highest diplomat, Kaja Kallas. Kallas, the EU’s foreign policy chief and former prime minister of Estonia, has publicly fantasized about the disintegration of Russia into ‘smaller states’.

In her meeting with Wang Yi, the Politburo member responsible for foreign affairs, she insisted that Russia must be ‘defeated’ outright, pressing the point so stridently that Wang felt obliged to explain that such an aim could hardly be China’s policy towards its neighbour. Absurd that he should have to spell it out; China’s strategic position is, after all, not that of Estonia. A Russia fractured by violent internal conflict would be anything but harmonious for China’s region. Were Russia to descend into civil war, a vast expanse, stretching from Eastern Europe through northern Eurasia to China’s borders, would dissolve into chaos.

The belligerent tone of European leaders reinforces, on the Chinese side, the image of an ideologically aggressive West, expansive and domineering by its very cultural core. Chinese intellectuals such as Jiang Shigong (强世功) call this the ‘Roman spirit’—and are they wrong? That Roman image, needless to say, does little to reassure the Chinese about supplying processed rare earths to our defence sectors.

It is a pity that (liberal) Europeans should appear so warlike to Chinese eyes, for much of Europe’s aggressive rhetoric is mere posturing, moralistic bluster dressed up as courage. Properly understood, Europe and China share the same fundamental interests in the war in Ukraine: a swift and durable ceasefire, and the avoidance of further escalation.

China has, from the outset, called for a truce; it has not recognized Russia’s territorial gains (including the annexation of Crimea in 2014); and it supplies no weapons to Moscow. Those are important facts. There remains fertile ground for Sino–European relations.

Half-Hearted Attempt

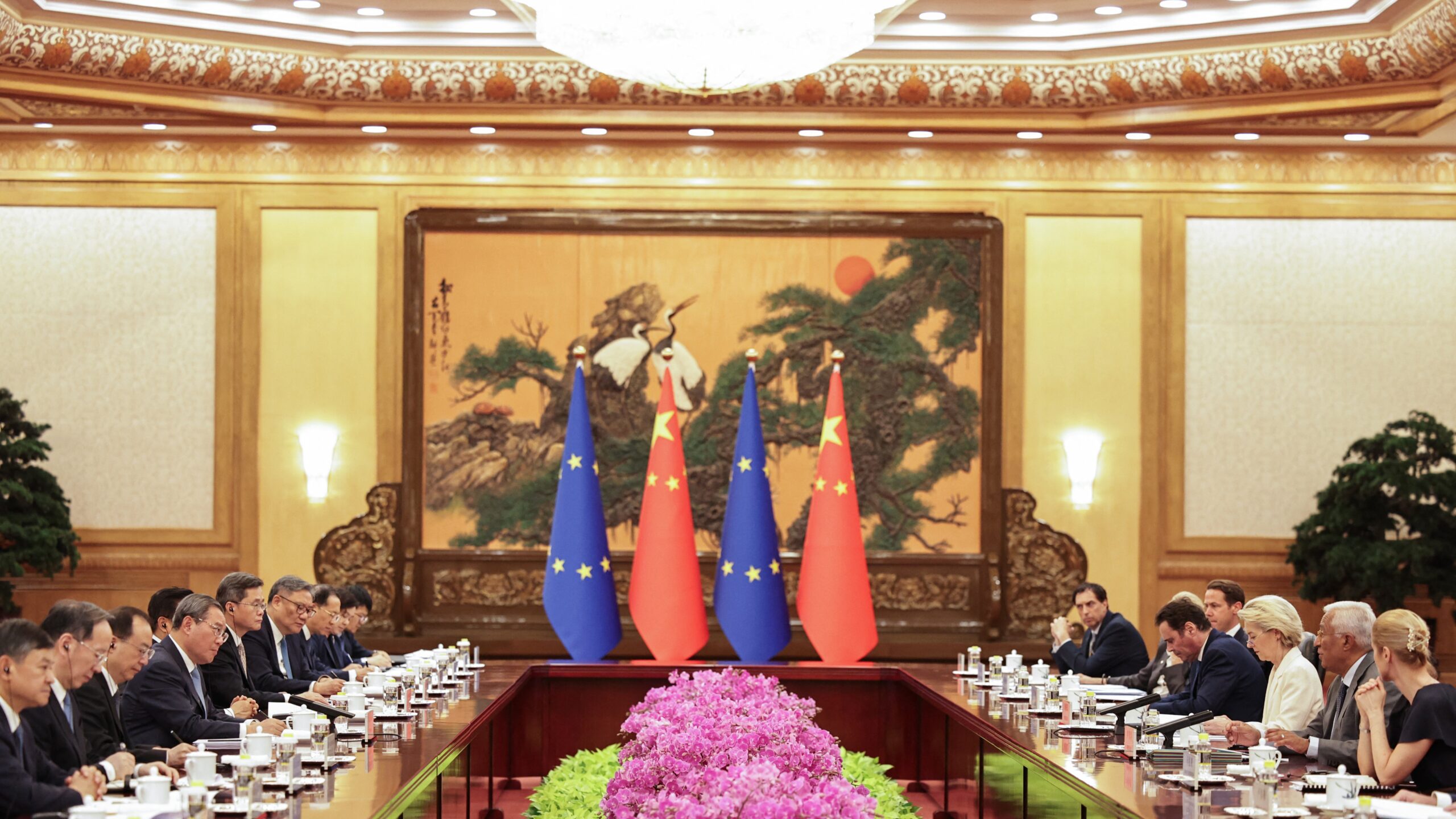

Now, the European Commission did make an effort to strengthen relations with China, though a distinctly half-hearted one, which culminated in the EU–China summit of 24 July in Beijing. The results were meagre. And the events surrounding the summit told of the Commission’s lack of strategic competence.

‘The events surrounding the summit told of the Commission’s lack of strategic competence’

Driven by a vague intuition that Europe and China might find mutual reinforcement at a time when the Kremlin wages war in Ukraine—a bloody display of badao—while the White House bombards the world with its economic badao, the European Commission had initially requested a summit with Beijing.

Yet the Commission could not find the right state of mind. European diplomats came across as accusatory, as I also heard first-hand from Chinese counterparts. The somewhat far-fetched reproach was that China should have sacrificed its relationship with its northern neighbour in favour of European interests.

To make matters worse, Kaja Kallas’s team, for reasons unknown, leaked details from confidential pre-summit discussions with Wang Yi.

The Chinese responded by cutting the meeting, originally planned for two days, down to one. No senior officials came to meet the European delegation at the airport; the envoys were simply put on a bus on the tarmac. Embarrassing.

Afterwards, Ursula von der Leyen declared that the summit had been a success in implementing her derisking policy: ‘We are carefully implementing a de-risking strategy.’

An absurd claim. One hardly needs to rush to Beijing with the entire EU leadership in order to derisk. Creating distance can easily be done from a distance. When the Commission first requested the summit in the spring, it must surely have had another plan in mind.

The Idea Itself

The problem lies in the very idea of derisking itself. It produces precisely the kind of strategic illiteracy that so typifies the Commission, its foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas, and Western European liberals more broadly. Derisking sounds ostensibly balanced and cautious, yet it is rooted in the imagination of a cosmic struggle, a battle between Good and Evil.

On one side, the Good—liberal democracies, progress, the West, truth, rights, freedom, equality, and so on. On the other, the Evil—immorality, human rights violations, ‘corruption’, ‘nationalists’, and ‘authoritarian regimes’.

With the latter, one wishes to have nothing—or at least less—to do.

And this is precisely why such a moralized worldview cannot yield strategic thought. To deem others corrupted and to preserve one’s own moral purity by keeping a safe distance is no workable basis for exploring the plurality of the world’s political systems, cultures, and ideologies—let alone for forging strategic connections within that plurality.

Derisking also came up during one of the conferences on Sino–European relations at which I recently spoke in Beijing. A European scholar reminded the assembled Chinese and European experts that one of the subcategories of derisking is called ‘partnering’, according to the European Commission’s theoretical framework. This, she hoped, might somewhat soften concerns about the concept.

But a Chinese EU specialist intervened. She pointed out that ‘partnering’, as defined in the official EU documents, is further specified as cooperation with ‘like-minded partners’. And yes, the Chinese experts on Europe are perfectly aware of what that means: in other words, not with China.

Thus derisking remains trapped in a worldview that ultimately lumps Russia and China together, explicitly or implicitly, into a single moral category: that of ‘authoritarian’ contamination.

Yet the two powers have entirely different political systems, civilizational backgrounds, and relations with Europe. In this way, derisking thought narrows Europe’s diplomatic room for manoeuvre and, more fundamentally, constrains its intellectual imagination.

Related articles: