On 30 October 2025, the National Rally (NR) managed for the first time to have a bill it submitted adopted by the French National Assembly.

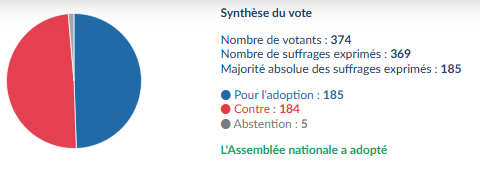

This bill, which is ‘aimed at denouncing the Franco–Algerian agreements of 1968’, passed with 185 votes for and 184 votes against. What are the implications?

Guillaume Bigot, RN MP for the Territoire de Belfort’s 2nd constituency, opened the session with the following arguments: ‘Imagine a contract: a contract that binds you to a partner who doesn’t respect any of their commitments; a contract where you owe everything, and your partner owes nothing; yet a contract that you continue to scrupulously respect, in both spirit and letter.’

This contract exists: it is the Franco–Algerian agreement of 27 October 1968. The excellent report that our colleague Charles Rodwell devoted to this agreement refers to a ‘veritable status’ for Algerians in France, one that goes completely against common law. This is particularly true regarding social benefits.

Under common law, a foreigner must reside in France for five years to receive the RSA (basic income support), family allowances, or the activity bonus; for an Algerian, this requirement disappears. A foreigner must reside in France for ten years before being eligible for the minimum old-age pension; an Algerian is entitled to it after only one year.

This extremely exceptional regime also extends to border crossings: Algerians can be absent from France for three years without losing their residency permit, compared to six months for other foreigners. A residency permit can be revoked from a foreigner who disturbs public order or practices polygamy; this is not possible for an Algerian.

Another exception: family reunification. An Algerian can bring their family over while earning only the minimum wage—including social benefits—whereas standard law requires much more from other foreigners.

Even more extravagant, in certain areas, the 1968 agreement favours Algerians over French citizens. For example, when an Algerian student wants to open a business, the administration is not allowed to verify the legitimacy of the business, whereas it can do so for a French student.

‘Nearly 40 per cent of Algerians aged 15 and over are neither employed nor in education’

We will be told that this is the price to pay for integration, but the Rodwell report demonstrates the contrary. The unemployment rate in Algeria is more than double that of mainland France. The employment rate of Algerian immigrants is 14 points lower than the national average. Nearly 40 per cent of Algerians aged 15 and over are neither employed nor in education.

They are simply inactive, many living on social assistance.

The session was particularly heated, with the right and the left exchanging a great many invectives. Guillaume Bigot notably accused the left of belonging to the ‘parti de l’étranger’—which is to say, of acting as foreign agents against France: ‘Indeed, in the 19th century, the royalists sided with foreign powers since they supported Prussia; in the 1930s and 1940s, the fascists and collaborators supported Germany; in the 1960s, the Communist Party supported the Soviet Union! And today, you are the party of Algeria!’

Let our Francophone readership judge for itself if it will take the time to read through the session’s minutes, or let our Anglophone readership, if they have a similar curiosity, translate said minutes using an online tool of their choosing.

SOURCE: French National Assembly

The President of the Ecologist Group at the French National Assembly later rendered the centre responsible for the outcome of this session: ‘the absence of Macron’s supporters gave the National Rally a victory on a racist text, and we were one vote short.’

During the session itself, after the RN was called the ‘party of the SS’ by a left-wing MP, Guillaume Bigot replied: ‘We will not let you do this, we will not be intimidated! When you call us xenophobic and racist, look two-thirds of the electorate in the eye, who agree with us!’

Although a symbolic victory for the RN, which had always in the past had its initiatives blocked by the arc républicain (the French equivalent of the cordon sanitaire), the bill has been described as ‘homeopathic’ by souverainiste spearhead Pierre-Yves Rougeyron, who argued the following in a 6 November 2025 Front Populaire interview:

‘Does the 1968 agreement grant Algerians easier access to French territory? Yes and no. When you manage to overturn this agreement—if it ever does—under what law will Algerian immigration be governed? Classical immigration law, EU law. The necessary framework for bringing in immigrants is in place. So, once you’ve given up on tampering with this particular law, you can vent your frustrations on the 1968 agreement if you like. It will have a rather negligible effect.’

In the same interview, the interviewer asked Rougeyron about a quote by Jordan Bardella, who declared in a Journal du Dimanche interview that his objective was ‘not to leave the European Union, but to take back our essential sovereignties.’

Rougeyron considers this nonsense: ‘He says that in Europeist language, in a Europeist newspaper…Sovereignty isn’t McDonald’s, it’s not “Welcome as You Are”. Sovereignty is something extraordinarily logical and extraordinarily material. A disabled person who can’t walk hasn’t delegated their sovereignty to their wheelchair; they can no longer, physically, walk. When you’re no longer sovereign, you can no longer, physically, do things. Sovereignty isn’t theoretical: it’s you can or you can’t.’ The souverainistes are sceptical of the RN’s ability to have the European Union change course from the inside, even in the event of a victory for them in the 2027 French presidential elections.

Related Articles: