This article was published in Vol. 2 No. 4 of the print edition

As a result of the Russian–Ukrainian War, which broke out in February 2022, the European Union introduced sanctions against Russia, including restrictions imposed on the import of certain energy carriers. The purport of these Union-wide measures, enforced against what is the largest energy supplier on the continent, is best understood from a perspective based on the recognition that energy is the main pillar supporting the operation of the economy. If the supply of energy is not secure, economic production will not perform at an adequate level. This raises the question of how the restrictive measures affect the energy security of Europe. In what follows, I will examine the factors shaping the EU’s energy dependency on Russia and, consequently, how these restrictive measures impact various aspects of our energy security.

Energy Carrier Measures Adopted by the EU

Starting in February 2022, the EU imposed a number of sanctions on Russian-sourced energy as follows.

As one of the first measures, Germany suspended work on Nord Stream 2, an undersea pipeline which had been planned to transport gas directly from Russia to Germany.

As part of the fourth package of sanctions, adopted in mid-March 2022, all European investment in the Russian energy sector was prohibited.

The fifth package, adopted in early April 2022, imposed a ban on the import of Russian coal, to the value of 4 billion euros per year.

The sixth package, adopted in early June 2022, includes an embargo on Russian oil, with exceptions—in deference to objections by Hungary, among others—granted to energy carriers supplying by pipeline.

It is important to note that the EU has had some restrictions on trade transactions with Russia since 2014, which marked the inception of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. These restrictions notwithstanding, Russia (a continent-sized country) remained he number one energy supplier to Europe in respect of both natural gas (39.2 per cent) and crude oil (24.8 per cent), based on 2021 data, and of coal (55.6 per cent), based on 2020 statistics. At the same time, Russia was second only to Nigeria among the largest importers of uranium from the EU, accounting for 20.2 per cent in the total.

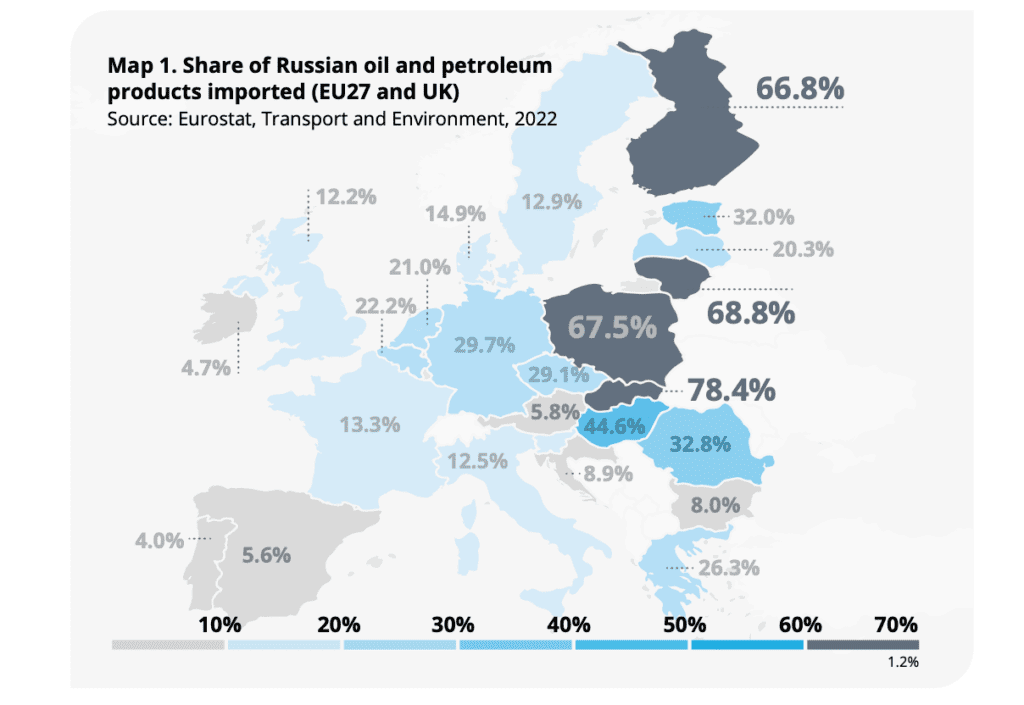

Another thing to consider is the fact that each European country has a different level of exposure to Russia. This varying degree of vulnerability is evident in the ratio of Russian imports in the total of the energy needs of each, but geographical situation also plays a role. Major factors include whether the EU member state in question has a seashore and how far it is located from alternative suppliers, such as Norway, the United Kingdom, or the Near East. Established infrastructure is another important starting point, given that its transformation entails very high costs when it comes to oil and gas, and even nuclear energy. (Where a country sources fuel for its nuclear power plants or refineries matters a great deal.)

The increasingly stringent enforcement of sustainability guidelines came with unpleasant side-effects

Moreover, one must keep in mind that, even though the EU made efforts to reduce its energy dependency on specific geographical regions and resources while promoting alternative energy sources, the increasingly stringent enforcement of sustainability guidelines came with unpleasant side-effects. From a low of 50.0 per cent in 1990, the EU’s dependency on energy import skyrocketed to 58.4 per cent in 2008, followed by a period of fluctuation, then another record of 60.5 per cent in 2019, and finally a declining trend that reached 57.5 per cent in 2020.

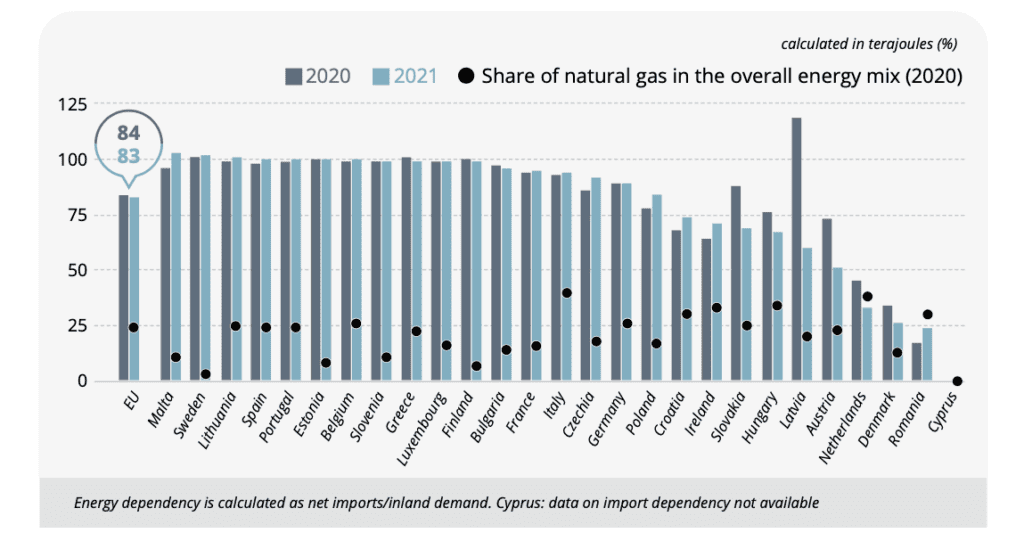

The energy dependency of the EU’s member states is also a function of the ratio of each energy carrier in the mix of resources used by a given country. By and large, all 27 member states have become net energy importers since 2013. In 2020, Malta, Cyprus, and Luxembourg relied on imported energy almost exclusively, at rates of between 92.5 per cent and 97.6 per cent. In the same year, the lowest rates of energy import dependency were posted by Estonia (10.5 per cent), Romania (28.2 per cent), and Sweden (33.5 per cent).

Overall, the EU sources 24.4 per cent of its total energy needs from Russia. The specific energy structure of individual member states compared to the rate of Russian import in their respective totals varies significantly. In 2020, rates of dependency on Russia were highest in Lithuania (96.1 per cent), followed by Slovakia (57.3 per cent) and Hungary (54.2 per cent). The least dependent on Russian energy were Cyprus (1.7 per cent), Ireland (3.2 per cent), and Luxembourg (4.3 per cent).

Energy Security and Its Most Important Factors

Energy security is essentially a function of the availability of energy as the cornerstone of a sound economy. One of the various aspects to consider has to do with problems of sustainability and scarcity, such as the exhaustion of non-renewable resources and their harmful impact on the environment. Moreover, the uneven geographical distribution of a specific resource tends to create logistical problems and makes pricing sensitive to market supply. As a result, energy security presents a complex challenge.

Energy security rests on three pillars: security of supply, prices, and environmental considerations, which also imply questions of access, operational security, and social well-being. The security of supply presupposes readily available energy (in part a function of geographical location) and its stable and consistent production. Affordable prices mean a further criterion of energy security. The third major factor involves environmental considerations, including those of sustainable development and energy efficiency. Although they are essential, these environmental considerations often prove difficult to reconcile with the first two factors. Switching to alternative resources can be expensive, and the stability of production is often precarious, owing to the vagaries of weather conditions. Operational security presupposes that energy quality and the requisite infrastructure are in place, forming a sort of transition between the security of supply and environmental sustainability. (Energy quality has several components, including long-term accessibility and minimized environmental burdens.) The well-being of society requires affordable energy and, once again, the long-term availability of energy offering the lowest possible rate of environmental pollution. Accessibility has to do with the geopolitical aspects of secure supply, along with the affordably low costs of energy production.

Energy Security and EU Sanctions

The embargo on Russian import implemented by the EU must be examined in its details, considering each constituent element of energy security. Using the set of concepts and criteria outlined above, including geographical features, we can gain a deeper understanding of the political position of those member states that have refrained from the abrupt and full-scale adoption of these sanctions.

Security of Supply

The security of supply equals the availability of resources on offer, which is contingent upon the given country’s geographical position and the stability of production. EU member states display significant differences in terms of their access to energy carriers, depending on their proximity to or remoteness from sea routes and hydrocarbon producing countries. Map 2 shows the ratio of oil and petroleum products imported by the EU’s member states and the UK.

Russia and the greater the distance from suppliers such as Norway or hydrocarbon producing states skirting the Mediterranean, the heavier the reliance on Russian imports.

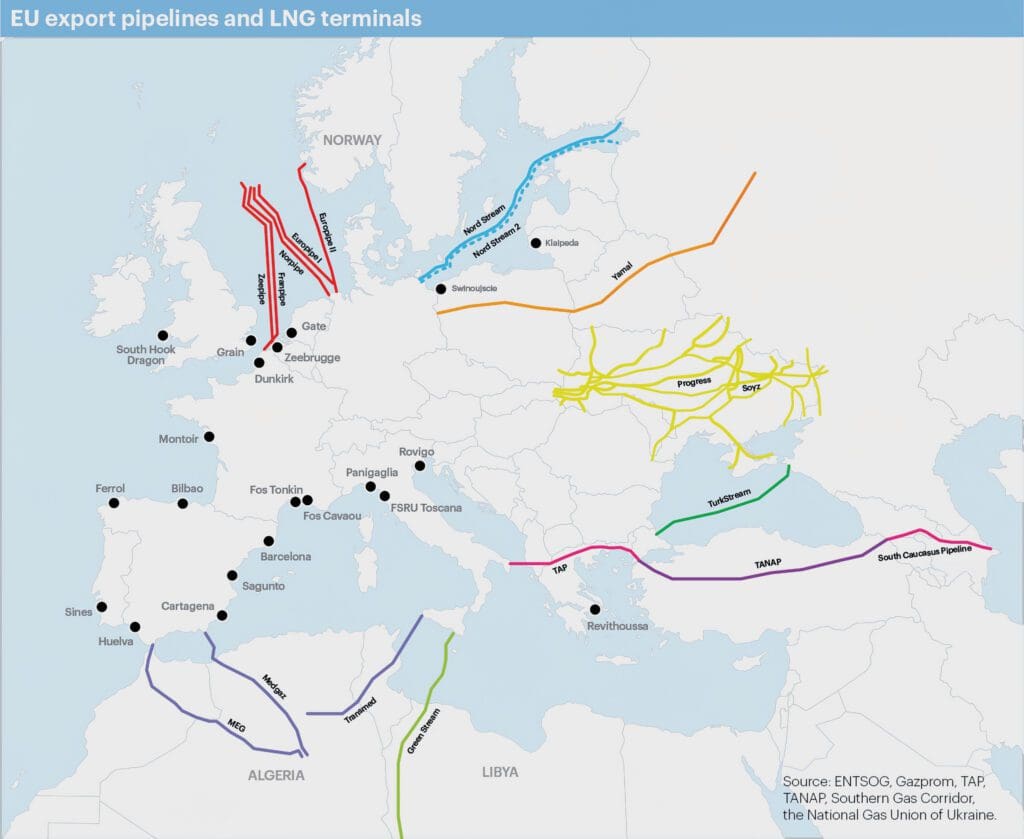

Map 2 illustrates how Europe is also divided in terms of each country’s access to gas supply. Member states in the North, West, and South enjoy alternatives relieving dependency on Russian gas, although they too have limited ways of receiving piped gas depending on their links to the Maghreb or northern fields. While installing LNG terminals is certainly an option for all European countries, those with a seashore remain in the most favourable position. Spain has a special advantage in that it is linked more directly to all the seas of the world through the Atlantic. Consequently, Spain operates the largest number of LNG terminals of all the member states of the EU (indicated by black circles on Map 2).

Landlocked countries, particularly those in East Central Europe, are more vulnerable because they have only indirect access to liquid gas. A case in point is Hungary, which must rely on agreements with Croatia for its LNG capacity.

East Central Europe, including the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary, is predestined to have a higher level of dependency on Russian energy by its landlocked geographical position and historical heritage. Here Poland is the exception, as it has a sea coastline and has built an LNG terminal of its own. Overall, however, the region’s geographical properties and existing infrastructure both prioritize access to Russian gas. (The significance of infrastructure in place will be addressed shortly.)

It is also true that—as a report by Eurostat duly points out—no scrutiny of dependency on Russian gas can be complete without regard to potential interruptions in import supply, which may have an impact on the share of gas in the total structure of energy needs. Factoring this into the equation (see Figure 1), import dependency in Sweden, Finland, and Estonia approaches 100 per cent, even as the ratio of gas in their energy mix is relatively low (3, 7, and 8 per cent, respectively). Meanwhile, Italy shows the highest ratio of gas in its energy composition (40 per cent), accompanied by an import dependency of 94 per cent. The Netherlands is second on the list in terms of the share of gas in its energy mix, but it is far less dependent on imports due to its established domestic gas production. Hungary’s reliance on gas is lower than the European average and shows a declining trend.

Another point to consider is the role of traditional suppliers of resources such as oil or nuclear energy. Switching a refinery to oil sourced from a new supplier means a vast investment, and options for obtaining uranium are severely limited given that nuclear power plants are optimized for fuel from a specific source.

Affordability

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, demand has shrunk consistently. European governments introduced a variety of measures to mitigate the effects of the 2021 price explosion and to protect their citizens. These measures, implemented by 23 member states as well as Norway and the United Kingdom, can be divided into six groups as follows. (1) Cutting taxes or waiving VAT on energy (for instance, in Austria, Belgium, Croatia, the Czech Republic); (2) regulating retail prices (Hungary, Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania, among others); (3) regulating wholesale prices (France, Portugal, Spain); (4) subsidies for needy social groups (almost all member states); (5) subsidies introduced through state-owned companies (Cyprus, Greece, Portugal) or (6) for the benefit of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs, for instance in Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia).

Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán recommended that the EU adopt three measures to cut energy prices

Some countries, including Italy and Spain, have urged joint action toward creating Union-wide strategic reserves and the common sourcing of natural gas needs. On 4 April 2022, at an international press conference, Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán recommended that the EU adopt three measures to cut energy prices. In harmony with similar initiatives from other member states, these proposals would, if implemented, make life much easier for both market actors and consumers. They include the temporary suspension of the carbon-dioxide quota system, the separation of wholesale electricity prices from gas prices, and the provisional abolition of the requirement for a bio ethanol component in fuels. A number of member states have formulated positions similar to these Hungarian proposals. The Czech Republic has argued for rethinking the emission trading scheme, and France is urging the reform of the pricing mechanism for the European energy market. The separation of electricity and gas markets was recommended in the summer of 2021 by Spain, and the idea has been supported by Portugal, Belgium, Italy, France, and Hungary. The Czech Republic abolished the requirement for mixing bio components with fossil fuels on 11 March 2022. While the measure introduced by Prague is mainly aimed at curbing escalating fuel prices, decision-makers in Brussels hope that it will help relieve some of the pressure on food and animal feed markets. Along much the same lines, Greenpeace and several other green organizations have in recent weeks urged EU member states to halt the manufacture of biofuels from food materials.

Environmental Considerations

Attention to the environment has become a key policy-making point in the EU, and has moved even further to the forefront in connection with the sanctions introduced against Russia. However, despite the long-term benefits of according top priority to the environment, in the current phase the EU faces a trend towards rising energy dependency (up to 60 per cent from 40 per cent in just a decade) and pronounced volatility in production capacities.

A case in point for the latter problem is Germany, where the share of renewable resources reached 40 per cent of the gross energy produced in the country in 2021. This trend is offset by days with adverse weather (no sunshine, no wind) which cause a lull in the production of alternative energy. On such days, the deficit is compensated by power from gas turbine plants. This phenomenon underscores the need for additional development and a pre-planned, progressive switchover. All things considered, the idea of an instant switch to alternative energy resources, for all the support it receives under the pressure of geopolitical conflict, cannot and should not justify an abrupt overhaul of the structure of energy production, if only because of the current state of technology and assets.

Operational Security

Operational security is, as we have seen, a matter of the stability and efficiency of energy production, as well as of having the requisite infrastructure in place. The latter requirement implies several aspects in addition to the massive costs of financing the alteration of existing capacities.

Even though the EU is linked to Russian petroleum by pipelines, much of the import is delivered by tanker ships bound for European harbours. Some 75–80 per cent of oil sourced from Russia is delivered on from the Baltic and the western ports of the Black Sea, and in lesser part from terminals in the Northern Polar region, while the remainder arrives directly through the Friendship pipeline. In 2019, the quantity delivered on this pipeline accounted for 4–8 per cent of the EU’s total oil import, supplying refineries in Poland, Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic.

Generally, the main priority in oil transport is security and safety, augmented by considerations of efficiency and costs. Despite being far from perfect, pipelines remain the cheapest, least hazardous, and most environmentally friendly method of transporting oil. On the evidence of statistical data, they are also safer, more efficient, and less energy intensive than other solutions. Conversely, pipelines can be problematic due to the inherent difficulty of (often trans-border) regulation and round-the-clock monitoring, not to mention their high maintenance demands. Pipeline transport demands an enormous initial investment, and its burden on the environment is the most severe. In addition, even when pipelines are up and running there are potential risks to the natural environment, especially when they are routed through a vulnerable ecosystem. That stress, however, is reduced greatly by the fact that, as a closed-loop, zero-discharge means of transport, a pipeline is void of hazards such as impairing air quality, damaging the ozone layer, precipitating acid rain, or disturbing wildlife beyond its sheer physical presence. Another benefit is the much lower quantity of any spills and the attendant mitigation of the likelihood of explosion in transit. Furthermore, pipelines have a minimal space requirement, and are both typically laid underground and routed through areas less densely populated or otherwise used than is the case with other methods of transport. As such, a pipeline accident tends to entail far less catastrophic consequences in its zone of operation.

According to current estimates, 60 per cent of the oil used around the world reaches its destination by tankers

Analytic reports have identified transport by tanker ships as being safe and efficient, with a notably high ratio of problem-free deliveries. These tanker ships are eminently suitable for transporting large quantities of oil over international seas and other waterways. One disadvantage, however, is that this option may be precluded or restricted by the geographical position of the receiving country, as is the case with Hungary, where at best it can be used in combination with other methods of transport. That said, there is no disputing the rise of international demand in tandem with the growth of the petroleum industry and, as a result, the increasing popularity of delivery by sea. According to current estimates, 60 per cent of the oil used around the world reaches its destination by tankers. While they are favoured for their efficient and relatively even performance, they are far from hazard-free. Oil pollution from tankers is rare, but when it does happen, it can cause massive environmental harm that lasts for decades. Here, the crux of the problem lies in the sheer quantity of the oil being transported—up to four million barrels by each of the largest tankers. Spills caused by accidents in tankers are much more difficult to contain, not to mention the speed with which they spin out of control as they often occur in locations remote from potential help. Oil spills spreading across the water surface cover a large area, potentially affecting shoreline ecosystems and disturbing the interaction and food chains of wildlife species.

Railways and trucks can present an alternative only where the delivery distances and the quantities being transported are relatively small. If the conditions are in place, these solutions can be very flexible and, in the case of transport by rail, entail low fixed costs. Railway is a useful option over longer distances and for large quantities, although it is not as flexible as HGV transport. The small diameter of tracks and wagon wheels, along with their potential fragility depending on age, construction quality, normal wear and tear, and exposure to the elements, increase the risk of failure under the huge load travelling on such narrow metal surfaces. Trucks face similar hazards, compounded by traffic and road conditions. Like trains, lorries are a more risky method of delivering oil compared to other transportation options, owing to their higher dependency on human factors.

Social Well-Being

Social well-being rests on the compatibility between environmental demands and affordable energy prices. In this regard, governments must not only consider the mandate to switch over to sustainable resources, but also make sure to prevent the energy supply for citizens from coming under the threat of scarcity or excessive pricing. This is the component of energy security most affected by the challenge presented by the sanctions.

Even before the Russian–Ukrainian conflict, prices had been rising sharply in the energy carrier sector, impacting consumer prices. The relaxation of stringency measures adopted in the wake of COVID-19 led to an abrupt increase in demand, while the supply side, with its capacities decimated by the pandemic, was unable to keep up. This situation was aggravated by the sanctions imposed on Russia, because they caused the supply of fossil energy on offer to shrink, driving prices up still further. The governments of Europe introduced several measures intended tohandle this predicament, winning the support of the European Commission as we have seen. Yet the fact remains that no meaningful, long-term moderation of global energy market prices can be achieved until the Russian– Ukrainian conflict is settled.

Access

The most immediate risk of the embargo introduced in 2022 consists precisely of the geopolitical factors discussed above. The war affects 4 to 8 per cent of oil deliveries to Europe via the Friendship pipeline which traverses Ukraine. Seen in this light, each country becomes subject to the impacts of the war in different ways.

The pipeline mainly supplies oil to the states of East Central Europe, all landlocked countries with the exception of Poland. Therefore, they have no direct access to oil transported by sea, and thus the EU sanctions are not currently applicable to oil delivered by pipeline. Russian gas delivered through Ukraine accounts for a similar share in European consumption, at about 8 per cent. At the same time, some countries enjoy diversified transport options. For example, most Russian gas now reaches Hungary via Serbia. The overall European perspective, however, has not focused on the safety and security of supply, i.e. those of the pipelines passing through Ukraine. These considerations have been upstaged by the decision to support Ukraine against Russian aggression.

Conclusion

Some of the EU sanctions against Russia concern energy carriers of critical importance for the economy of Europe. Russia remains the number one supplier of oil, gas, and coal in the region, and this inevitably causes the sanctions to have a direct impact on energy security, and thus on the sound operation of the economy of every European country, although in varying ways and degrees. Indeed, several of the constituents of European energy security described in the foregoing are subject to peril under the sanctions in force, including the stability of supply, accessibility, and the steady operation of refineries. The mitigation of other threats, for instance those of a geopolitical nature, coincides with the need to scale back the threat to these previous components of security. All the while, as a side effect, the armed conflict has catapulted the criteria of sustainability to the foreground.

None of this, however, changes the fact that each member state has a different geographical situation, different levels of existing infrastructural development, and different recourses to the safe, secure, and reliable transport of resources. In particular, no member state finds it as difficult to substitute Russian-sourced resources as the countries of East Central Europe. Accordingly, the general switchover must be a deliberate and incremental process, mindful of the specific situation and the needs of each member state. A higher share of alternative resources in total—something that the EU has advocated for some time—may be of key importance in the drive for diversification, as may be agreements along the lines of the one signed between Hungary and Croatia for the use of the latter’s LNG terminals.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel

NOTES

1 Lawrence Carley, Energy-Based Economic Development (London: Springer-Verlag, 2014), https:// link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4471-6341-1.

2 European Commission, www.consilium.europa.eu/ hu/policies/sanctions/restrictive-measures-against- russia-over-ukraine/history-restrictive-measures-against-russia-over-ukraine/https:/www.consilium. europa.eu/hu/policies/sanctions/restrictive-measures-against-russia-over-ukraine/history-restrictive- measures-against-russia-over-ukraine/.

3 Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_ imports_of_energy_products_-_recent_ developments&oldid=564016#Main_suppliers_of_ natural_gas_and_petroleum_oils_to_the_EU.

4 Unlike that of other fossil energy carriers, the utilization of coal has been shrinking at an almost steady rate for the past decade. Another major difference with coal is that it is available from domestic production for many member states, including countries in East Central Europe, such as the Czech Republic and Poland.

5 Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Coal_production_and_ consumption_statistics.

6 Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Nuclear_energy_ statistics#Uranium_supply_security.

7 Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics- explained/index.php?title=EU_energy_mix_and_ import_dependency.

8 Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics- explained/index.php?title=EU_energy_mix_and_ import_dependency.

9 Takaaki Furubayashi and Toshihiko Nakata, ‘Preliminary Study of Energy Security and Energy Resilience Evaluation in Japan’ (11 January 2017), Researchgate.net, www.researchgate.net/ publication/312545860_Preliminary_study_of_ energy_security_and_energy_resilience_evaluation_ in_Japan.

10 Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20220419-1

11 www.vg.hu/energia-vgplus/2022/04/igy-csokkentenek-orban-javaslatai-az-europai-rezsikoltsegeket.

12 Giovanni Sgaravatti, Simone Tagliapietra, and Georg Zachmann, ‘National Policies to Shield Consumers from Rising Energy Prices’ (13 June 2022), https:// www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/national- policies-to-shield-consumers-from-rising-energy- prices/.

13 András Major, ‘Az EU fő klímafegyverét is hatástalanítaná Orbán Viktor a rezsicsökkentés érdekében’ (Viktor Orbán Would Deactivate Even the Main Climatic Arm of the EU in Order to Lower Utility Costs), Portfolio.hu (11 April 2022), www.portfolio.hu/gazdasag/20220411/az-eu-fo-klimafegyveret-is- hatastalanitana-orban-viktor-a-rezsicsokkentes- erdekeben-538771.

14 Aiden Leibel et al., Transportation of Oil and Gas, n.d., https://web.uvic.ca/~djberg/Chem300A/ GroupLM_OilGasMovement_Proj1.pdf.