As we enter 2026, the election looms in Hungary. On 12 April of this year, the Hungarian people will go to the polls to elect a new government. As the world changes around them rapidly and a major war continues just across the border, Hungarian voters must decide: will they continue to entrust Fidesz with the authority to lead them through the geopolitical storm, or will they take a bet on Péter Magyar’s Tisza Party to lead Hungary with a new style of government?

We will know the outcome in a few weeks. Yet in the run-up to the election, the mood—both domestically and internationally—seems strangely mixed. It certainly feels like the momentum behind the Tisza Party’s initial surge has run out. Tisza’s messaging seems to have strayed from the initial burst of optimism that accompanied Magyar’s rise into a sort of aggressive paranoia. In his New Year’s speech, Magyar shocked the country by saying that in the coming weeks, there would be acts of sabotage by drone carried out by the government to prevent him from becoming Prime Minister. These are not the words of a self-confident candidate.

Despite this, people in Hungary and especially in the rest of the world seem divided on whether Fidesz can maintain its hold on power. This is mainly due to the mixed signals being given by the election polling. If you take the overall polling on the election seriously, it shows that Fidesz and Tisza are running neck and neck, with Tisza having a slight lead. But the problem with taking these polls at face value is that, as I highlighted in Hungarian Conservative early last year, there is reason to believe that the polls are being manipulated.

The problem is that pollsters aligned with the government are giving vastly different readings than pollsters aligned with the opposition. If you believe the former, Fidesz have a roughly 7-point lead over Tisza; if you believe the latter, Tisza have a roughly 10-point lead over Fidesz. A roughly 17-point difference between polls cannot simply be attributed to error: one set of polls is fake. Since I highlighted this in Hungarian Conservative, the Wikipedia article on the election polling—which is the main source for polling data for journalists and interested observers—has acknowledged this problem, listed the pollsters by affiliation and separated out the government-aligned polls from the opposition-aligned polls.

‘Pollsters aligned with the government are giving vastly different readings than pollsters aligned with the opposition’

The question, of course, is which set of polls is fraudulent? In my previous article on the topic, I gave two reasons why it is likely that the opposition-aligned polls are phoney. First, it is the opposition-aligned polls that are showing the most extreme and unbelievable results. For example, a mid-December poll run by 21 Kutatóközpont showed Tisza with a 17-point lead over Fidesz. It is not even clear to me that this is mathematically possible, given the composition of the electoral map—it seems to imply that rural voters who have been solidly Fidesz for years have switched en masse to Magyar’s insurgent party. This is not impossible, but it seems unlikely—especially since it is so out of whack with both the other polls and with previous electoral history. Secondly, I noted that we have seen fraudulent polling used in other countries—like Georgia—to skew the sense of electoral reality amongst the electorate to get them riled up.

We are not close enough to the election, and we now have enough polls to run some statistical tests that will give us more insight into which ones are real and which ones are fake. Here we will use some econometric techniques that are quite technical, but they should be explainable quite easily in intuitive terms. Our methodology is to separate the government-aligned polls and the opposition-aligned polls and compress them through what is called a ‘Hodrick-Prescott filter’ (HP filter). This then allows us to calculate what in econometrics we call the ‘cyclical component’. This cyclical component shows us how large the errors are in the polling relative to the overall trend being shown by the pollsters.

Let us try to understand this intuitively. When we look at a series of polls, what we are seeing is a very large aggregate of data. Each poll is undertaken by calling hundreds or thousands of people and asking them their opinion of the upcoming election. The result is then averaged to get the final poll result. This creates the result of a single poll. But when we are looking at the trend of polls over time, we are seeing multiple separate polls being carried out within days or weeks of the previous poll. In theory, unless something dramatic happens, these polls should change quite slowly. The poll today should look a lot like the poll taken earlier in the week, which should look a lot like the poll taken the previous week. If there are large differences between these polls, this indicates that there may be something wrong with the polling. The cyclical component helps us to detect this.

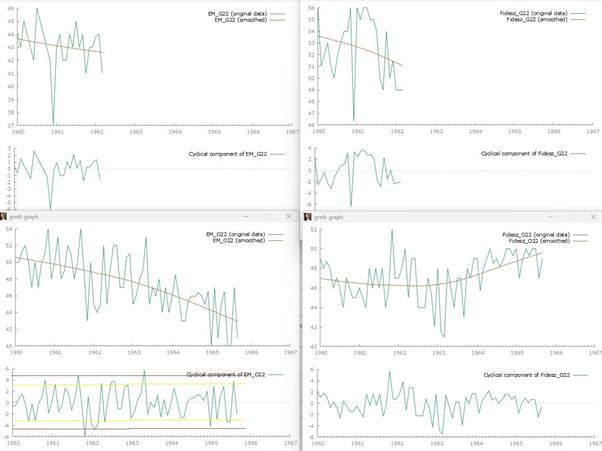

The charts below show the polls, the polling trend (HP filter) and the cyclical component. On the top, we have the opposition-aligned polls for Tisza (left) and Fidesz right and on the bottom, we have the government-aligned polls. The government-aligned polls have a shorter length because the opposition-aligned polls are much more numerous—in the previous article, I called this ‘polling inflation’ as it skews the overall polling averages in favour of the opposition-aligned polls.

Now, let us focus on the cyclical component of each poll. The cyclical component of the opposition-aligned polls that try to detect Tisza’s popularity is enormous and tends to fluctuate between +7 and -6. The cyclical component of the opposition-aligned polls for Fidesz, however, is much more muted. Today’s Tisza poll from the opposition-aligned pollsters often disagrees significantly with yesterday’s, but when the opposition-aligned pollsters’ poll for Fidesz’s popularity, this is not the case. One interpretation of this is that when Tisza is having a hard week in politics, opposition-aligned might publish very favourable results for Tisza in their poll to help rally support.

When we look at the government-aligned polls, the situation is very different. The cyclical component of polls of both Tisza support and Fidesz support is much more muted and ‘normal’. We do see one big spike in the cyclical component for Tisza at the beginning of the polls, but this is likely due to Tisza’s rapidly growing momentum when they first came on the scene. A statistical move of this sort is well-known to throw off an HP filter. The fact that we do not see this spike in momentum in the opposition-aligned polls is actually a sign that they might not be as real as they seem, in a sense, to anticipate Tisza’s rise rather than capture it—although this point is open to debate.

These tests seriously call into question the reliability of the opposition-aligned polling. They have an extremely high cyclical component when they poll for Tisza support, meaning that different polls from opposition-aligned pollsters radically disagree with each other. This is very suspicious, especially since they seem able to poll Fidesz support without these enormous discrepancies. It might also be interesting to compare the polls for the 2026 election with the polls previously run for the 2022 election. Here, we will use the polls from the same pollsters and once again divide them into opposition-aligned and government-aligned pollsters. This time, the latter are on the top, and the former are on the bottom.

Here, we do see that the cyclical component for the previous opposition coalition, United for Hungary (Egységben Magyarországért, ‘EM’), in the opposition-aligned polling was higher than in any other group. But the cyclical component was much more muted in 2022 than it was for Tisza in 2026. In 2022, EM’s cyclical component in the opposition-aligned polls ranged between +5 and -4, a substantially larger gap (9) than the +7 and -6 gap (13) that we see in the 2026 opposition-aligned polling for Tisza. When we compare the opposition-aligned polls for 2026 with the same pollsters’ work for 2022, we once again see statistical discrepancies, calling further into question whether this polling is real and accurate.

It should probably be noted that the pollster with the most accurate prediction of the election results in 2022, Magyar Társadalomkutató, was a government-aligned poll. Just under two weeks before the election, this pollster predicted that Fidesz would win by 11 points—they ended up winning by 19.6 points. Some opposition-aligned pollsters were publishing polls in the closing weeks that were close to reality—showing an 8-to-10-point lead for Fidesz—but others were publishing highly inaccurate polls, some showing an under 4-point lead for Fidesz.

Taking all the evidence together—from the intuitive unreasonableness of some of the opposition-aligned polls, to the statistical analysis, to the previous track record of pollsters—it seems far more likely that the opposition-aligned polls are inaccurate than that the government-aligned polls are. We cannot say this with certainty, of course, but the weight of evidence is vastly on the side of the government-aligned polls being accurate. This raises the uncomfortable question: are the opposition-aligned pollsters fabricating poll data, and if not, how do they explain the extremely high cyclical component in their polling?

Related articles: