This article was originally published in Vol. 5 No. 3 of our print edition.

In Western discussions around multilateralism versus multipolarity,1 we often encounter the implicit or explicit assumption that the former would tend towards peace and stability, while the latter would tend towards conflict and be inherently unstable, eventually breaking down and producing war. However, both depend much on other factors for their functionality, such as the quality of communication, the clarity on and acceptance of the ‘perimeter of its business’, and the commitment of the parties to it. These elements are decisive for the sustainability of either system, and for enforcing it when challenged. In their absence, neither provides for stable peace: in the last century, multipolarity decayed into the First World War, and multilateralism collapsed into the Second World War.

We could think of the 1930s as a time when the failure of multilateralism allowed a war-prone multipolarity to re-emerge. Or we could see the world as having been multipolar all along, a fact only concealed by the multilateralism embodied in the League of Nations. In the first view, multilateralism was an instrument of peacekeeping, unsuccessful insofar as it did not preclude the outbreak of war. In the second view, it was a distortion that fatefully hindered understanding of the real power relations, thus contributing to the outbreak of war.

Great Powers, Reshuffled

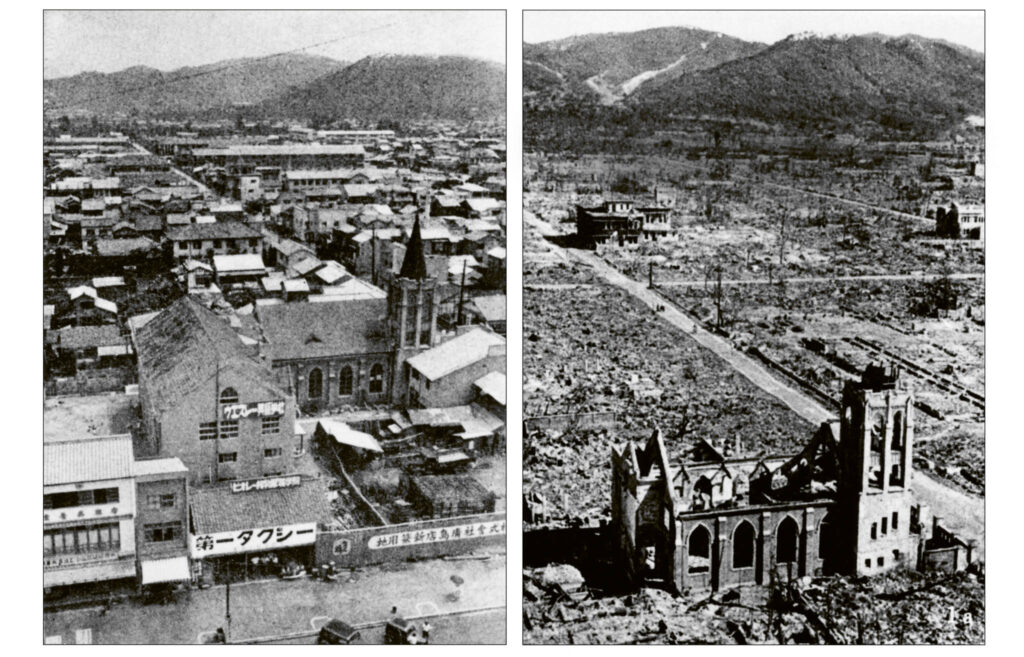

In 1940, multipolarity was concentrated around five centres (leaving aside the sixth, France, which had been placed hors-jeu): Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In 1945, Germany and Japan were in ruins, the Soviet Union had lost about 25 million people as well as over half of its industrial base, and the UK had gone from controlling Earth’s largest empire to being one of Earth’s most indebted nations, with much of its infrastructure destroyed. In contrast, the United States had lost ‘only’ about 400,000 soldiers in the entire war, and its cities and industries were intact. In the mid-1940s, the US economy produced half of the world’s GDP. Of its four potential peer competitors, three had been disabled, and the remaining one had a reach that was essentially confined to land: the Soviet Union focused on dominating a geographical continuum from the Pacific coast to the River Elbe, but was so weakened by the war that, in the short term at least, it had no capacity to extend beyond Central Europe or into the global maritime domain.

In essence, we can therefore conceive of the mid-1940s as a period of unipolarity, a status underlined by the American monopoly on the atom bomb. And it was in that period that the contemporary multilateral order, first and foremost the United Nations Organisation, was established.

Re-Ordering the World

To understand this order, one should bear in mind that in contrast to the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and the treaties drafted in Paris in 1919–1920, there was no peace settlement after 1945. Technically, the Cold War—very aptly named in this regard—was one big frozen conflict. The UN did, at least occasionally, function as a forum in which the non-aligned states and groups such as the G772 could ‘de-polarize’ world affairs, and beyond that, much global politics happened outside the US–Soviet rivalry.3 The multilateral system of the Cold War was not designed to democratize or Sovietize the world, but to pacify international relations between states with different structures and political outlooks, on the condition that they respect the fundamental rights and obligations laid down in the UN Charter. This was an inclusive global forum.

The international arrangements that the two main powers of the Cold War would use as hegemonic tools were established separately—some earlier, such as the International Monetary Fund in 1944, and others later, e.g. the OECD in 1948 and NATO in 1949, or Comecon in 1949 and the Warsaw Pact in 1955.4 In a sense, such arrangements were minilateralisms serving the respective geopolitical ends of the two great powers (the non-aligned G77 could perhaps be considered an example of ‘minilateralism light’ in its own right).5 While these minilateral arrangements had an important function as tools for US or Soviet power extension and projection, the UN and forums such as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (today’s OSCE) or the Council of Europe had a bridging role.

From the Eclipse of Soviet Minilateralism…

Each of these minilateral arrangements rested on a strong centre. Accordingly, Soviet minilateralism declined: communism as an ideology and socialism as an organizational form had lost much of their credibility and functionality even before 1989. The quelling of contestations or revolutions in the Soviet sphere, such as in Eastern Germany 1953, Hungary in 1956, and Czechoslovakia in 1968, had reduced the Soviet system’s appeal to Western Europeans (and not just them). Other foreign operations, such as in Afghanistan 1979–1989, further globalized this effect.

But the eventual fall of the Soviet Union was perhaps most of all a product of the increasingly severe internal under-performance of the Soviet system, which contrasted—ever more visibly—with the narratives of progress on which the USSR rested. This led an increasing proportion of the citizenry to change their outlook from socialism to cynicism, detaching themselves from the state and thus precipitating its final fall.6 The Moscow-dominated minilateralisms became increainsgly hollow, and Soviet soft power shrank steadily both within and beyond its own sphere.

Soviet hard power disappeared with the Union itself, and did so to an extent that presented the post-Soviet Russian Federation with severe problems, as seen, for instance, during the First Chechen War of 1994–1996. In economic terms, the reorganization after 1991 offered opportunities, of which a good number were realized through decentralization during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin (1991–1999), but this period was also marked by negative changes, including the concentration of wealth in a small oligarch class while both Russia’s GDP and the life expectancy of the general population fell sharply.

…to the ‘Unipolarization’ of Multilateralism

Throughout all this, the multilateral structures of the Cold War continued to exist. However, as the gradual decline of the Soviet system in the 1970s and 1980s had already reduced its potential to challenge Western liberalism and capitalism, both became more unhinged. With the Soviet Union gone, many in Western capitals believed that it had been their better policies (i.e. political decisions) and better polities (i.e. political and economic systems) that had brought down the Soviet Union, rather than the latter’s internal dysfunction and decline. The mindset that this produced, especially in Washington, is encapsulated in Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History.7 The disappearance of the Soviet Union also meant that the most important brake on American power projection was gone. The US-led interventions in Bosnia in 1995, Kosovo in 1999, and Iraq in 2003 were nails in the coffin of multilateral restraint.

One lesson we can draw from this is that the capacity of global multilateralism to function depends on the degree to which it remains in line with the underlying global power distribution. After the demise of the Soviet Union, there was no sufficiently large counterweight to American hegemony, and it is only now, after more than two decades of unipolar interregnum, that China is starting to emerge as a potential counter-hegemon, with BRICS/BRICS+ still in the early stages of evolving into a form of counter-minilateralism (and while there is no guarantee that it will, it looks as if it could). So, while post-1945 multilateralism made it through the unipolar moment, it is today ever less representative of the reality of global power distribution. The key observation here—as has been pointed out by authors like Arta Moeini,8 among others—is that the construct of global order is not the same thing as the reality of the global system.

System vs Order

The years after 1989 were even more unipolar than those after 1945. On the one hand, some Western forms of minilateralism were extended for cooperative rather than hegemonic purposes. The G8 and G20 can be considered examples of this. On the other hand, the EU and NATO were enlarged to encompass Central and Eastern Europe as well as some Balkan countries, which in geopolitical terms meant the displacement of what was left of Moscow’s influence. Finally, Western forms of economic minilateralism, such as the IMF and GATT/WTO witnessed particularly significant expansion, becoming multilateral institutions that came to include almost all states of the world while remaining dominated by the West, albeit to a lesser degree over the years.

‘The capacity of global multilateralism to function depends on the degree to which it remains in line with the underlying global power distribution’

So, from the European perspective, ‘system’ and ‘order’ looked aligned: the collective West dominated both. It also expanded its key minilateralist structures into Central and Eastern Europe. While not without challenges, this was nevertheless a process that ran relatively smoothly, as these societies share a deeper, broader, and longer-standing European bond than they have with, for instance, Russia. Neither Soviet domination nor communist ideology could change this (indeed, they rather reinforced it). In any case, most Western decision-makers assumed that globalization and liberalization would characterize the twenty-first century. There were of course influential exceptions to this rule: Samuel Huntington, for instance, warned of the potential for civilizational conflict,9 and John Mearsheimer always emphasized the point that realpolitik has by no means disappeared.10 But as far as the Western political establishment was concerned, globalization and liberalization were the future. The ‘end of history’ type of progress was the rule, and hiccups such as the 2007–2008 financial crisis were the exception. In other parts of the world, however, observers drew different conclusions.

Two Examples of Non-Western Outlooks

In general terms, the evolution of the views held by the Chinese establishment can be described with reference to three landmark texts. The first, Unrestricted Warfare, was authored by two Chinese air force officers and is a treatise on strategy in international relations of the ‘no war, but also no peace’ kind.11 While the book does contain observations on the changing nature of war, it is less a tactical manual than a political treatise. It examines at length how to increase China’s capacity to deny foreign coercion by achieving parity or superiority in both military and non-military capacities.

The second text is the Chinese military’s Political Work Guidelines of 2003, which contain the doctrine of the ‘three warfares’: psychological (subversion), legal (lawfare), and opinion (controlling the narrative, including in supra-national forums such as the UN).12

The third text is the ‘Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere’, or ‘Document No. 9’ for short. It was circulated within the Chinese Communist Party and then made its way into The New York Times in 2013.13 It contains a list of Western ideas and policies that the CCP opposes internationally and views as threats internally. That includes Western universalism, individualism, and progressive liberalism. To give an example, the Chinese establishment has always considered the WTO to be a purely commercial and technical regime—unlike the Western establishment, which expected economic liberalization to precede political liberalization. Thus, from the moment of China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, the two establishments saw themselves as being on different journeys, but this was only understood in the West much later. On this, it is enlightening to read Rush Doshi’s analysis of the Chinese ‘build-up’ of a displacement strategy against US-dominated unipolarity, which he sees as starting as early as 1989.14

Unsurprisingly, China and the West hold diametrically opposing views on the viability of the Western political and economic model. While Western elites seem to consider the state of affairs to be generally stable, with events such as the 2007–2008 financial and the 2015 migration crisis arising as transitory challenges, the Chinese view seems to be that these are symptoms of profound, structural decay. The inference in political terms is that Western societies have been destabilized by over-liberalization—a diagnosis shared by many observers within the West.15 The conclusion in economic terms is that the Western situation is untenable because, on the one hand, it is de-industrialized and over-financialized, and on the other hand, it has import dependencies, including of energy, that are compounded by overstretched supply chains that have choke points outside the West’s control, such as Suez, Hormuz, and Malacca. (Additionally, there are non-geographic choke points, for instance in IT systems.16)

The Russian establishment developed similarly negative views regarding the West’s future evolution, but over a different timescale and different geographical immediacy. The early post-Cold War minilateralist structures devised by Russia, such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (1991) and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (1992), were put in place to limit the extent to which post-Soviet Russia would be subject to Western influence in its ‘near abroad’.17

Nonetheless, this did not preclude cooperation. After the Warsaw Pact had dissolved, NATO started preparing for expansion, but it also established close dialogue with Moscow: its ‘Partnership for Peace’ programme with Russia started in 1994, followed by the signing of the NATO–Russia Founding Act in 1997, and this led to the NATO–Russia Council in 2002. While the ensuing fallout between the Atlantic and Russian elites was gradual, the Munich Security Conference of 2007 was perhaps the most symbolic milestone on this road. President Vladimir Putin gave voice to the discomfort that NATO expansion was causing in Russia, but also criticized what he saw as a general lack of European commitment to creating a common security architecture. He declared that his country had transitioned from socialism to democracy, but would neither become culturally Westernized nor strategically vassalized by American imperial ambitions.18

The inspiration for Russian foreign policy includes such sources as the Primakov doctrine of the late 1990s, Alexandr Dugin’s ‘fourth political theory’ of the late 2000s, and the Karaganov doctrine of the early 2020s. Primakov19 reflected on how to best navigate and mitigate the unipolar world order, including, among other steps, by pivoting to India and China. Dugin20 presented a set of hypotheses derived notably from Samuel Huntington’s texts on civilizations in international relations and from Carl Schmitt’s concept of ‘greater space’ (Großraum).21 He argues for a global organization structured by civilizational spheres, with each organized around one political (or, put more bluntly, imperial) centre. Karaganov22 developed a hard-line combination of Primakov and Dugin into a call for the mobilization of the ‘global majority’ into a common movement for the de-Westernization of global politics.23 He has also advocated for the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons, including against NATO countries.24

In practical terms, the Primakov doctrine was most impactful. Notwithstanding arrangements such as the Eurasian Economic Union (2014), which reflects a Duginian approach to dominating one’s civilizational sphere, the forms of minilateralism that are really important to Moscow are not controlled by it. The two prime examples would be the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (2001) and BRICS/BRICS+ (2009/2023), which are of interest to the Russian government not as tools for increasing its ‘intra-civilizational’ reach (Dugin), but as ways to limit and eventually overcome US-dominated unipolarity (Primakov) without resorting to head-on brute force against NATO (Karaganov). However, Russia’s attack on Ukraine corresponds more to a Duginian or Karaganovian than to a Primakovian approach.25 This shift in foreign policy thinking is likely to intensify the longer the Russia–Ukraine War lasts, and risks becoming one of the war’s strategic legacies.

Adapting Europe’s Horizon to the New Paradigms

In light of all of this, Europeans need to rethink where they are and where they want to get to internationally. First, we need to understand that the transitional period that we are currently living through is unlike the re-ordering periods of the twentieth century. These were dominated by Atlantic power(s): the re-ordering of 1919–1920 was essentially devised by France, Britain, and the United States, and the periods around 1945 and 1989 were characterized by US unipolarity. In contrast, the current transition is predominantly an Asiatic moment.26 We cannot therefore ‘copy-paste’ the foreign policy thinking and assumptions of the twentieth century to today.

We need to look further back, to two earlier historical transitions that might offer some lessons for Europeans today.27 These are the bloc formation of the 1890s and 1900s28 (as an example of what to avoid) and the ‘balance of power’ multipolarity established after the Napoleonic Wars29 as an example of what might be useful—especially if it is done in support of multilateralism. And this is where Europe can play a useful role.

To elaborate, the view currently dominant in the United States seems to be one of multilateralism as opposed to multipolarity. While not necessarily invalid, it is to some extent the result of confusing the construct of international order with the power distribution of the international system. Multilateralism can pacify the international system, but in order to do so, it has to properly reflect the geopolitical realities of today’s multipolarity. In contrast, if it distorts the view on it, it might prevent decision-makers from clearly perceiving the real situation, and thus increase rather than decrease the potential for conflict. The latter is also the case if multilateral institutions are being instrumentalized for hegemonic ends. A multilateralism that is responsive to global multipolarity could avoid the mistakes made in the periods preceding the First and Second World Wars that were pointed out at the very beginning of this piece.

This would represent an important challenge for US–European relations, and that is the second point here: while being dependent on a functioning multilateral order, Europe does not have sufficient capacity—or, perhaps, will—to really engage with the international system. To be fair, that is also a result of the fact that such engagement was the prerogative of Washington and Moscow for some forty years, and then of Washington alone for another twenty-something years (though France might to some extent be considered an exception to this).30 Europeans were ‘on holiday from history’, but the holiday is over. As the Cold War-induced comfort—and illusion?—of transatlantic unity withers, Europeans see that there is a great imbalance between their dependency on the order and their lack of capacity to influence its underlying system.

‘Multilateralism can pacify the international system, but in order to do so, it has to properly reflect the geopolitical realities of today’s multipolarity’

As a consequence, they need to keep multipolar competition as much as possible within multilateral structures. This requires skilled diplomacy, especially since greater powers such as the United States, China, and Russia might view multilateralism (albeit to varying degrees) as a potential hindrance to increasing their power in the multipolar competition. The main caveat is that in order to achieve this, the multilateral institutions need to remain free of attempts to use them as tools for exporting social norms (Western or other). It is only under this condition that they might prove useful in pacifying a shifting system.

This brings us to the third point: outside one’s own country, there is no merit—and no virtue—in judging others by the degree to which they comply to one’s own social standards, unless perhaps these standards are mutually shared. Where they are not, travelling the world and lecturing foreign societies is a useless endeavour, and an insulting one at that.

Beyond the ethical reasons for refraining from such behaviour, there is also a utilitarian one. The post-1945 institutions rest on three pillars, the first being the conceptual framework of liberal internationalism,31 the second a procedural framework based on states as the primary organizing units of the international structure, and the third the collective enforcement of the agreed-upon rules, if approved by the UN Security Council as the ‘gatekeeper’. Thus, while modern multilateralism is conceived of in terms of liberal inspiration, the actual working of it—procedures and enforcement—are not. If the Europeans were to continue putting an increasingly ideological and rigid primacy on the first to the detriment of the second and third, then multilateralism will perhaps remain as a shell, but be lost for practical purposes. Powers like the United States or China could navigate such a world relatively easily, Europe much less so.

Conclusion

By moving away from the unipolar mindset and getting back to the idea(l) of inclusive multilateralism, European policy-makers could help to keep the system-level competition of multipolarity within the fundamentally pacifying parameters of order-level multilateralism. Rather than underwriting the view that multilateral institutions would be arenas for the export of social and cultural norms, Europeans should reinvigorate these institutions as forums for interest-based diplomacy. And by being responsive to changes at the system level, multilateralism can contribute to maintaining peace during the shifts in the balance of power that we are currently living through. Europe’s peoples would benefit from it, as would their governments’ reputation and diplomatic standing in the world.

NOTES

1 For reasons of space restriction, this article will not go into the reflections around ‘multipolar’ and ‘multinodal’ world organization.

2 This group was created in 1964, originally with the aim of coordinating the economic interests of its 77 founding states in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Today, the group comprises 134 states and plays an important role as a platform for the ‘Global South’.

3 So-called ‘bipolarity bias’ led to some severe misinterpretations on the part of both Moscow and Washington on what was part of the Cold War and what was not. Regarding the Vietnam War for instance, US Secretary of Defence Robert S. McNamara (in office 1961–1968) himself pointed out much later in the Fog of War documentary (2003) that the US administration saw primarily as a ‘Cold War activity’ what the Vietnamese saw chiefly as a fight for national self-determination.

4 Regarding the characterization of such minilateralism as ‘hegemonic’ tools, see for example the chapter on ‘Sovereignty and the IMF’ in Jamie Martin, The Meddlers. Sovereignty, Empire, and the Birth of Global Economic Governance (Harvard University Press, 2022).

5 A concise theoretical assessment of multi-and minilateralism can be found in Abdul Fathah, ‘From Multilateralism to Minilateralism. A Conceptual Paradigm’, Defence Research and Studies (4 June 2022), https://dras.in/from-multilateralism-to-minilateralism- a-conceptual-paradigm/.

6 See Emmanuel Todd, The Final Fall. An Essay on the Decomposition of the Soviet Sphere (Karz, 1979) [first published in French in 1976].

7 Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (Penguin, 1992). Fukuyama himself has since moved away from this assessment in a number of aspects: see e.g. Liberalism and Its Discontents (Profile Books, 2022).

8 Arta Moeini is co-founder and research director at the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, based in the US and Canada. On the international system as opposed to the international order, see in particular Arta Moeini, ‘Why the Blob Needs an Enemy’, American Conservative (September 2020), and Arta Moeini et al., ‘Middle Powers in the Multipolar World’, Institute for Peace & Diplomacy White Paper (March 2022).

9 An argument he developed in an article published in Foreign Affairs in 1993 and later expanded into a book: Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (Simon & Schuster, 1996).

10 John Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001).

11 Wang Xiangsui, and Qiao Lang, Unrestricted Warfare (Echo Point, 2015) [first English translation published in 1999].

12 For a detailed appreciation of both the fundamentals and the applications of Chinese influence operations, see Paul Charon and Jean- Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, ‘Chinese Influence Operations. A Machiavellian Moment’, ResearchGate (October 2021), www.researchgate.net/publication/367252670_Chinese_Influence_Operations_ A_Machiavellian_Moment.

13 A translation of the document is available at https://digichina.stanford.edu/work/ communique-on-the-current-state-of-the-ideological-sphere-document-no-9/.

14 Doshi discerns three periods in Chinese strategy: one of ‘blunting’ US power (1989–2008), another of laying the foundations for Chinese power projection (2008–2017), and finally one of confronting US power in ever more arenas and on ever more levels, all the way up to global. See Rush Doshi, The Long Game. China’s Strategy to Displace American Order (Oxford University Press, 2021).

15 To name just two authors: Emmanuel Todd, La défaite de l’Occident (Gallimard, 2024); and Glenn Diesen, The Ukraine War and the Eurasian World Order (Clarity Press, 2024). Especially see Diesen’s remarks on ‘authoritarian liberalism’ and on ‘cultural decline and soft power’, 110–117.

16 The sudden halt of all air traffic during the widespread computer outage produced by a faulty Crowdstrike update in July 2024 was a powerful reminder of this.

17 On the notion of ‘near abroad’ and its geopolitical implications, see e.g. Gerard Toal, Near Abroad: Putin, the West, and the Contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus (Oxford University Press, 2017), or Yekaterina Kuznetsova, ‘The Near Abroad: Increasingly Far Away from Russia’, Russia in Global Affairs (8 February 2005), https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/articles/the-near-abroad-increasingly-far-away-from-russia/.

18 The speech is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQ58Yv6kP44.

19 Yevgeny Primakov was spokesperson of the last Supreme Soviet (1990–1991), then head of Russian Foreign Intelligence (1991–1996), foreign minister (1996–1998), and prime minister (1998–1999).

20 Alexandr Dugin is a political philosopher, editor, and writer. He has held positions as head of the Centre for International Relations and the Centre for Conservative Studies at Moscow State University (2008–2014).

21 Carl Schmitt, Völkerrechtliche Großraumordnung mit Interventionsverbot für raumfremde Mächte (International Territorial Order with a Ban on Intervention by Foreign Powers); a speech given at Kiel University in 1939 and published in book form by Duncker & Humblot in 1941.

22 Sergey Karaganov is professor emeritus at the Moscow Higher School of Economics and honorary chairman of the Russian Council on Defence and Security Policy.

23 See e.g. Marlène Laruelle, ‘Dés-occidentaliser le monde. La doctrine Karaganov’, in Le Grand Continent (20 April 2024), https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2024/04/20/desoccidentaliser-la-majorite-mondiale-la-doctrine-karaganov/.

24 For Karaganov, nuclear weapons exist due to divine intervention, giving mankind back the ‘fear of hell’ that it had lost. See Sergey Karaganov, ‘A Difficult but Necessary Decision’, Russia in Global Affairs (23 June 2023), https://eng.globalaffairs.ru/ articles/a-difficult-but-necessary-decision/.

25 For an assessment from a Western or NATO perspective, see for instance Gregorio Baggiani, ‘Karaganov’s Vision. Towards a World Majority’, NATO Foundation Defence College (July 2024), www.natofoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/NDCF-Baggiani-De-Westernising-Karaganov-en-def-r.pdf.

26 Some very good reflections on this come from, among others, top Singaporean diplomat and academic Kishore Mahbubani, ranging from The New Asian Hemisphere: The Irresistible Shift of Global Power to the East (PublicAffairs, 2009) to The Asian 21st Century (Springer, 2022).

27 To truly appreciate the extent and depth of the transition we are witnessing, the historical horizon needs to be widened still further, with an evaluation of the power shift that was induced by European oceangoing vessels and firearm technologies in the sixteenth century, but this would greatly exceed the space available for the present article.

28 These two decades saw the division of Europe into two opposing military alliances, the ‘Triple Entente’ (France, the UK, and Russia) and the ‘Triple Alliance’ (Germany, Austria–Hungary, and Italy). The automatisms of mutual defence led to the extension of what could have been ‘just’ another Balkan War into the First World War. See especially Christopher Clarke, The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914 (Penguin, 2012).

29 The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 functioned as a negotiating forum for the major powers of European multipolarity, i.e. Austria, Prussia, Russia, the UK, and, after some delay, France. While producing a quite peaceful century in Europe, it did not establish any permanent platform for discussing international matters; this would first be brought about with the League of Nations, established in 1919 after the end of the First World War.

30 While France was a founding member of NATO in 1949, from 1966 on it pursued a cooperative yet independent military policy as it left NATO’s integrated command (but not the alliance itself). It was the only country in either NATO or the Warsaw Pact that had no foreign bases on its territory. France re-joined NATO’s integrated command in 2009.

31 This was ideologically at odds with the Marxist–Leninist revolutionary doctrine, but the institutional design flowing from this liberal internationalism was accepted by the Soviet government as a temporary concession, seeing it as at most a delay, but not a hindrance to the eventual global spread of socialism.

Related articles: