France is in trouble. This is hardly a secret. The country has become ungovernable. Last week, Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu stood down from his post because he did not think that he could form a stable government. In response, a few days later, President Emmanuel Macron reappointed him. The situation is fast-moving from the genre of tragedy into the genre of comedy, and that does not bode well for France’s political or economic stability.

The problem is that the French government is spending too much money. In August of this year, just before the government collapsed, Finance Minister Eric Lombard warned that if the country did not get its act together, it would end up going to the IMF for a bailout. The French elite were so horrified by this statement that they sent former French Finance Minister and now ECB head Christine Lagarde out to say that the country would not need an IMF bailout. More comedy.

French bond yields are now higher than Italian bond yields. Italy has long been known as a hopeless case in Europe. Shortly after Prime Minister Georgia Meloni was elected in 2022, it became clear that she would have extremely limited capacity to govern Italy in the way that she had campaigned on. If Meloni got too far out of line—especially on issues related to the euro, spending or foreign policy—the ECB could always yank the leash and allow borrowing rates to rise. While the French elite might relish the possibility of reining in any future populist government, such a subordination of the French state to the technocrats in Brussels would arguably mean the end of anything resembling Gaullist France.

If you ask the average French technocrat what the problem is, they will no doubt tell you that it is France’s generous benefits system, especially as it relates to pensions. Economists will explain that the solution to this is to cut the benefits and bring down government spending. This may sound nice in theory, but in practice, it is highly unlikely to work. When President Macron tried to raise the retirement age in 2023, it provoked riots—and ultimately resulted in the political deadlock we see today. But even if the French people did accept these policies, raising the retirement age by a few years is not going to solve France’s problems. A new approach is needed.

‘When one sector in the economy goes into debt, another sector saves’

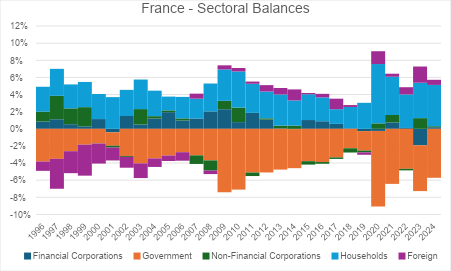

The clue here lies in France’s sectoral balances. What are sectoral balances? They are an economic framework based on the national accounts that allow us to understand the drivers of savings and debt in the overall economy. When one sector in the economy goes into debt, another sector saves. Economists often focus too much on the sector that is going into debt and too little on the sector that is engaging in saving—yet it, as we will see, takes two to tango. The chart below shows the sectoral balances of France for the past 30 years.

Here we see that the government is running deficits and has run deficits for a long time. We also see that, especially since the pandemic in 2020, those deficits have grown substantially. No wonder French bond yields are rising. But we also see that these deficits are flowing mainly into the household sector, which seems to insist on very high savings rates—the household savings rate is around 15 per cent versus 4–6 per cent in the United States and 8–10 per cent in the United Kingdom.

In fact, we see that French households have insisted on saving at high rates for the past 30 years. If French households spent more instead of saving, the economy would grow more quickly, tax revenues would rise, and French government deficits would not be nearly as much of a problem.

What we also see in the French sectoral balances, however, is that these high household savings rates were not always financed by high government deficits. Before the mid-2000s, and especially before 2000, French household savings rates were propped up by high rates of foreign dissaving. Translated into language that is easier to understand: before around 2006 France ran large trade surpluses and these trade surpluses allowed the French household sector to save without the French government having to facilitate this with very large government deficits.

So, the key question is: what changed? A moment’s reflection will tell us—the single currency was introduced. The introduction of the euro effectively tied the French economy to the German economy—and in doing so, tied the franc to the deutschmark. This meant that France could no longer devalue its currency if the economy started to lose competitiveness and the trade surplus began to shrink.

Locked into the constraints of the euro, France has lost competitiveness, lost its trade surplus and, since French households still want to save, the French government sector has been forced into deficit. Political instability has followed.

‘Locked into the constraints of the euro, France has lost competitiveness’

Is the solution, then, to leave the single currency? This is certainly an option. Although it is such a radical option that it seems unlikely that the current French political class would ever consider it. But what if there were a halfway house option: France could launch an innovative dual currency system. That is, France could continue to use the euro for domestic transactions, but it could reissue the franc for international transactions.

By allowing the new franc to freely float against the euro, the currency can find its equilibrium in world currency markets and return the French economy to competitiveness—and, if the country can regain its trade surplus, it can start to close that troublesome government deficit.

But is this even legal? Would the European Court of Justice not come down on the French government like a ton of bricks if it ever tried this? A glance at the relevant law would suggest that issuing a second currency would indeed be illegal. Article 128 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union states that the ECB ‘shall have the exclusive right to authorise the issue of euro banknotes within the Union’ and that these banknotes ‘shall be the only such notes to have the status of legal tender within the Union’. But in fact, this all hinges on the meaning of ‘legal tender’.

According to a Report of the Euro Legal Tender Expert Group (ELTEG), ‘there is currently some legal uncertainty at the euro area level with regards to a common interpretation and definition of legal tender and the consequences flowing from there.’ It notes that different member states have ‘very different national legislative provisions regarding the extent and use of legal tender.’ If you read this report carefully, you will find that the relevant law is far looser than it may first appear if you simply turn to Article 128.

Take the example of introducing a dual currency system in France. The new franc would not be used in domestic transactions. Nor would it be used in transactions in, say, Germany or Italy. It would only be used to settle trade. After a German company, for example, accepted francs for its goods, it would then convert these francs back into euros at the Banque de France. Can we really call this new franc ‘legal tender’ in any meaningful sense? Rather than legal tender, it could be argued that this system is simply one to facilitate the settlement of trade at market-competitive levels. As Germany’s Constitutional Court has highlighted, far stranger legal reasoning has been used to justify the ECB’s quantitative easing programme.

No doubt introducing a dual currency system would be a political fight. But at least it is a political fight that could be won in the courts through argument. Trying to close the French government deficit through spending cuts, on the other hand, is clearly a fight that cannot be won—either in French Parliament or, perhaps more importantly, in the streets of Paris. While the dual currency proposal may strike some policymakers as extreme, in reality, it is far less extreme than the proposition that France can engage in the sorts of spending cuts needed to close its deficit. It might be one of those ideas that is ‘just crazy enough to work’.

Related articles: